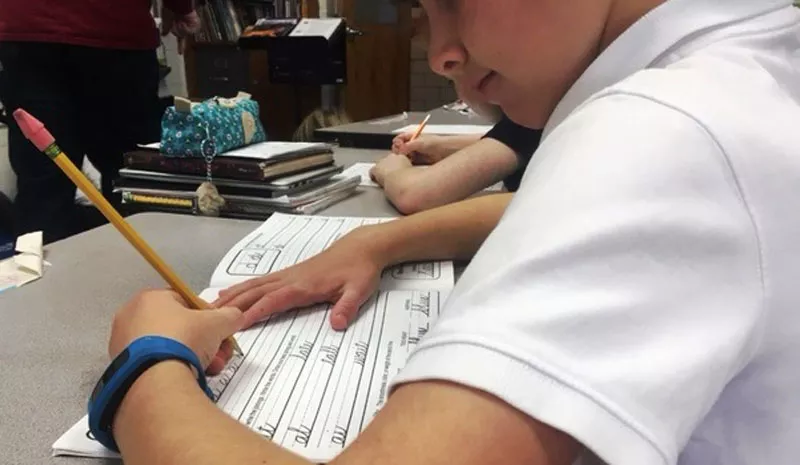

In Mark Wise’s third-grade classroom, each day begins and ends with ten minutes of cursive handwriting. He finds it’s an engaging and calming activity and an effective way to transition into learning after the opening bell and then to reflect and reinforce lessons of the day before the closing bell.

“The students are controlling their minds while controlling their hands,” he says. “It requires concentration and imagination.”

Wise teaches at Lyles Crouch Elementary School in Alexandria, Virginia, where he says teachers never cut cursive from the curriculum even as educators elsewhere consider it a dying art and a waste of valuable instruction time.

“I know we live in the age of technology, but there comes a time when technology fails,” Wise says. “There are many advantages to learning cursive and I think we should preserve it and prevent it from becoming a lost art form.”

The Common Core standards don’t require teaching cursive in public schools, emphasizing the digital age’s need for keyboarding skills instead. But cursive may be making a comeback because of—rather than in spite of— technology.

New technologies like Windows Ink from Microsoft and Interactive Ink from MyScript Labs use real-time predictive handwriting recognition, eliminating the need for a keyboard.

“Our new interactive ink technology combines the flexibility of pen and paper with the power and productivity of digital processing to create the best user experience in dynamic digital handwriting,” says Paddy Padmanabhan, CEO of MyScript.

With mobile, hand-held devices, handwriting can be a faster way to input data than keyboards. These technologies could be a win-win for both promoters and detractors of cursive.

Cursive advocates know the process of handwriting can enhance recall.

Cursive advocates know the process of handwriting can enhance recall.

Imagine a college lecture hall where some students are taking notes on laptops while others are taking them longhand. Whose notes are better?

Researchers have found that laptop users take more notes, sometimes recording every word from the lecturer, while the longhand note takers were slower and had to paraphrase while translating speech to paper. However, the process of transcribing enabled them to recall more of the information than the laptop note takers.

Meanwhile, other studies have shown that learning cursive not only improves retention and comprehension, it engages the brain on a deep level as students learn to join letters in a continuous flow. It also enhances fine motor dexterity and gives children a better idea of how words work in combination.

Another important check in the “pro” column: learning cursive may increase literacy.

The Economist reported on the research of neurophysiologists from Norway and France who found that different parts of the brain are stimulated when writing letters on paper, rather than typing them on a keyboard. The tactile practice of handwriting leaves a memory trace in the sensorimotor part of the brain, which are retrieved when reading the letters. In other words, handwriting reinforces reading in ways that keyboarding does not.

There are some wins for technology advocates, too. Digital technology that allows handwriting instead of keyboarding can combine the benefits of longhand with advances in technology. Sensitive touch screens can recognize everything from writing, drawings, and sketches to mathematical equations and music notations, turning them into digital files that can then be stored, searched, shared and edited collaboratively the same way current data is. The bonus is that the technology allows for spontaneous inspiration that can be captured more quickly than keyboarding alone.

“There’s a myth that in the era of computers we don’t need handwriting. That’s not what our research is showing,” Virginia Berninger, a University of Washington professor who has co-authored studies on cursive writing, told the Washington Post. “What we found was that children until about grade six were writing more words, writing faster and expressing more ideas if they could use handwriting—printing or cursive—than if they used the keyboard.”

The students in Mark Wise’s third grade classroom don’t need convincing. They have not only learned to write in cursive on paper, they are always eager to write in cursive on their Chromebook screens.

“They like how it looks, they like the freedom it gives them,” says Wise. “They become enchanted.”