[Editor's note: Congratulations to Columbus educators! After striking for three days alongside parents and teachers, they reached an agreement. The new contract includes: a guarantee that all student-learning areas will be climate-controlled by 2025-2026, and that all schools will get heating and air-conditioning; reductions in class-size caps at every level, lowering the number of students in every classroom by two over the course of the contract; and the first-ever limits on the number of buildings assigned to art, music and PE teachers, with scheduling intended to achieve one specialist per subject per building. It also includes limits on the number of district jobs that can be outsourced to out-of-town corporations, a ground-breaking parental leave program for teachers, and salary increases.]

Last fall, temperatures in Columbus, Ohio, hit 94 degrees. Just try learning long division in that heat.

Class sizes are high, too—regularly topping 30 to 34 students.

Columbus teachers know what their students deserve and need. It includes safe, well-maintained classrooms and the one-on-one, individualized attention that inspires students to reach their full potential.

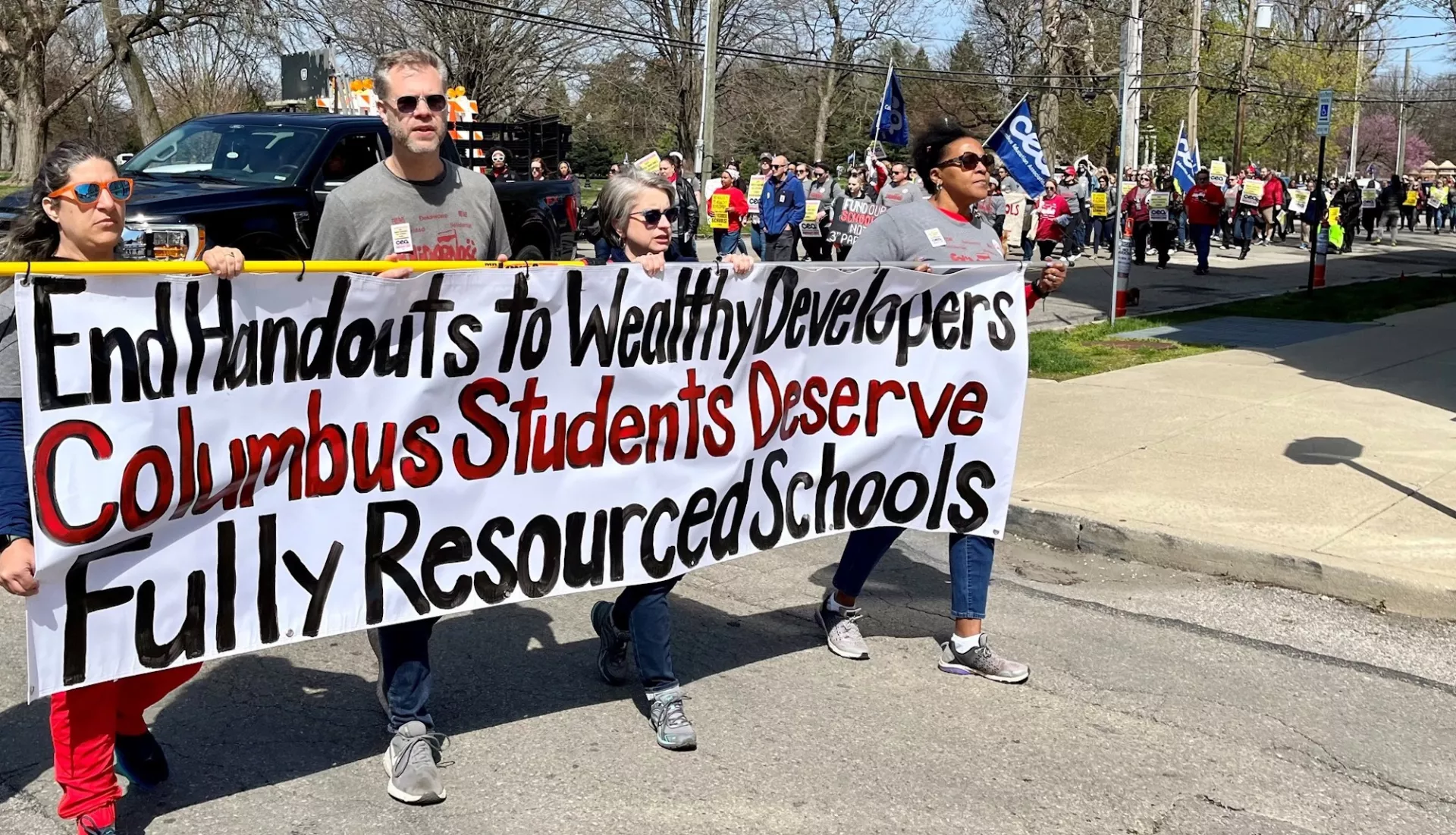

This is what the nearly 4,500 educators of the Columbus Education Association are fighting for.

Because Columbus students don’t have these things—and because district negotiators have refused to provide them during prolonged contract negotiations—CEA educators began striking on Monday. And, at picket locations across the city this week, parents and students joined them.

“We want more for our students in Columbus,” said Regina Fuentes, Eastmoor Academy teacher and CEA spokesperson.

Why are Columbus teachers on strike?

The three primary issues driving CEA members to take a stand are:

Class size: “How can one person attend to the academic and social-emotional needs of that many kids!” asks a Columbus teacher. With classes that regularly top 34 students, one teacher simply can’t attend to the specific, individualized needs of every student, every hour, every day. As class sizes grow, individual attention drops—this is simple math, teachers say.

Another math problem that confronts Columbus schools: Last year, the city gave away more than $50 million in tax breaks to real-estate developers and corporations, CEA pointed out. That money could have paid for an additional 534 teachers, which would have gone a long way to reducing class sizes and increasing the kind of attention Columbus students need and deserve.

Air conditioning and heating: On hot days, social studies teacher Joe Decker refrains from leaning over students’ desks to check their work. “I’m constantly worried I’ll drip sweat on a kid’s page!” he exclaims.

His school, Mifflin Middle School, has just a handful of reliably air-conditioned spaces: the main office, the computer lab, the library. Classrooms aren’t among them. Decker and his students make do with a noisy industrial fan that he bought himself at Lowe’s.

“Your heart breaks when you see kids wilting,” he says.

Roughly one-quarter of Columbus’ schools don’t have air conditioning—and the consequences for learning are chilling. Basic physical needs must be met for students to be ready to learn, educators say. “You tell the kids, let’s just do our best, but it’s almost like you’re diminishing what they’re going through,” says Decker. “We’ve had days over 100 degrees—and they’re increasing.”

For years, the school board has told educators that they’re working on it, but their lack of care and urgency is endangering students with asthma and educators with other health issues, he says. “We need this in black and white [in the contract.] We need to protect our kids. We need to protect educators.”

Well-rounded curriculum: Students in Ohio suburbs are practically guaranteed to have full-time art, music, and P.E. teachers who inspire their creativity, nurture their curiosity, and teach them teamwork and more.

In Columbus, however, it’s not uncommon for a single art or music or P.E. teacher to attempt to serve several elementary schools—which means one teacher could be responsible for several hundred students. It’s an impossible task, and it means Columbus students aren’t getting the education they need and deserve.

“I mean…come on! There is so much reading on how music is instrumental to the development of a young brain. That’s just a fact. To not provide these students with the education that they deserve, it hurts our society,” says Vera Allen, a Columbus music and theater educator.

Today’s marketplace is driven by technology, by creativity, by collaborative work. This is exactly what full-time art, music and P.E. teachers in every Columbus elementary school would provide to students—and teachers and parents know it, says Allen, whose 5-year-old daughter joined her on the picket line Wednesday. “I can’t even tell you how many parents and students were on the picket line today!”