Key Takeaways

- While many educators across the U.S. have won salary gains—through collective bargaining or legislative advocacy—too many still struggle to pay their basic bills.

- In Florida, which ranks 50th in the nation for average teacher salary, low pay is one factor in the educator shortage. That's why Florida educators are organizing for better pay.

- In other states, where educators are telling their stories and comparing their pay to other college-educated professionals, recent wins have boosted salaries.

You Should Be Able to Buy Strawberries

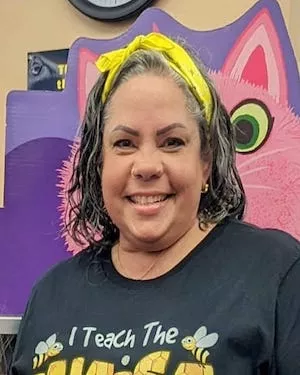

"I'm feeling a little anxious," says Florida teacher Tamara Russell, as she rolls up to the Costco cashier. Russell and her husband budgeted $250 for this twice-a-month grocery trip, but it's a struggle.

Apples, avocados, and other fresh fruits aren't cheap. Simultaneously watching your cholesterol and your checking account? Almost impossible.

The scanner beeps. Today's total is $211, including a $24 piece of salmon that will cost $12 after Russell splits it with another teacher. "Yes!" says Russell, celebrating with a little shout.

"You win!" says the cashier.

But who really wins when a National Board Certified teacher with 26 years of experience can't afford to buy a box of strawberries? Or prescription medicine?

Not her. Not her students. Not their community or state either. With a base salary of just $48,500, Russell can't win for losing.

And it's not just her. "I'm every teacher," says Russell, who teaches fourth-grade math and science at Beverly Shores Elementary, in Lake County, Florida. "Every teacher can tell you stories like this. We teach because we love it. Because we feel like we're changing the world every day. This is still the best profession in the world. But for the amount of love we pour into it, it breaks my heart."

Her hope is her union. "I don't want people to feel sorry for me. I want them to get organized with me. I want them to advocate alongside me. I want all of us to get organized and stand together," Russell says. "I believe in the power of collective action!"

We Went Shopping with Tamara: Listen Along!

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00How Florida Has Fallen

Last year, the average teacher salary in Florida ranked 50th in the nation, at $53,098, according to NEA's annual report of educator pay. Decades ago, when Russell began her career, Florida was ranked 30th.

Since then, the state's lawmakers have crusaded to divert taxpayers' money to private schools, starting with former Gov. Jeb Bush in the late 1990s.

Today, voucher programs abound. So do high-stakes tests for public school students. In 2011, then-Gov. Rick Scott passed a law linking teacher pay to student test scores, promising it would lead to higher scores.

It did not. Instead, the state now has incomprehensible pay systems, differing from county to county, relying on "value-added models" with a scaled number for every student.

Scott's law also eliminated tenure for teachers hired after 2008 and ensured that anybody who still has a multiyear contract can't get a bigger raise than a new teacher. Because of this, some teachers with decades of experience are paid just a few hundred dollars more a year than first-year teachers.

Test scores, teacher pay, and school funding have all gone down. Meanwhile, Florida's educator shortage is escalating. Midway through the last school year, Florida still was advertising for 7,553 K-12 jobs.

"We still have 145 staff vacancies," says Valerie Jessup, a union leader and paraeducator in Volusia County, Florida. "Paras, office specialists, custodians, bus operators, bus attendants—they will not fill these vacancies."

Low pay is not the only problem. Disrespect, safety concerns, and prohibitions on what Florida teachers can say about race, racism, and LGBTQ+ people also make it harder for teachers to do their jobs.

Average Teacher Pay in Your State

The Cost of Low Pay

Like Russell, Jessup loves her job, providing one-on-one support to a student in Volusia's special education program. But, after 8 years, it pays $16 an hour. Jessup gets more from the parents who hire her as a weekend and evening babysitter.

She and her husband, a school custodian, grow vegetables and buy rice in bulk to save money. Their 10-year-old son is on Medicaid because the school district's family health insurance plan would eat an entire paycheck.

"I could go to the Buc-ee's on the highway and start at $18 making sandwiches," Jessup says. "But I love my [students] too much to not be there. If I didn't do it, who would?"

Like Russell says, every Florida educator has stories like these. Zahira Peña-Andino, a test coordinator in Osceola County, has a master's degree, 17 years of teaching experience, and about $20 in her checking account.

"Right now, I'm making $2,600 more than a brand-new teacher in my district," she says.

Lee Wright, who teaches high school English in Osceola, left his old job in aircraft maintenance 11 years ago. Last year, after 10 years of teaching, he finally got back to his former salary: $52,500.

"There are days when I want to update my resume and reach out to the right people at the airport," he admits. "But I'm fulfilled as a teacher. I feel like I'm living out my morals and values."

Change Is Possible!

Florida teachers know what's possible when they stand together and fight back. In 1968, they first statewide walkout by teachers in the U.S. took place here, with 35,000 Florida teachers handing in their resignation letters to protest crumbling schools, a lack of textbooks, and continued segregation.

Their power led to the then-governor's political ruin and paved the way for the state constitution to be amended, enshrining public employees' collective bargaining rights.

These rights are critical: Research shows that, as a rule, union teachers get paid more than teachers without unions.

"This is absolutely, definitely the case," notes Sylvia Allegretto, a researcher who has produced the Economic Policy Institute's annual study of the "teacher pay penalty" for more than 20 years.

And the stronger the union? The better the pay.

Today, Florida union members are hopeful and resolute. They know Florida can do better.

In November, voters in 19 counties approved local tax increases that will pump money into their districts. For example, in Hillsborough, homeowners opted to pay an average $281 more a year to provide $6,000 salary supplements for teachers and $3,000 for school bus drivers and other educators. In Pinellas, a similar new tax will add $11,000 to teachers' salaries and $3,000 to support staff salaries.

Across the state, union members educated voters about the need for more funds. These votes show that "when we work together, we can win!" says Florida Education Association President Andrew Spar.

But it does take time and commitment. "A few years ago, we got 5 percent salary increases," Peña-Andino notes. "We got ourselves to school board meetings, we spoke up, and we signed petitions, and it definitely made a difference."

Pay is still lousy, thanks to state lawmakers, but educators like Russell know what it will take to win more. Speak up. Get organized. Elect candidates who support public education. Become active union members, she urges.

"Here's what I tell people," Peña-Andino says. "You can't complain if you're not doing your part."

Quote byTamara Russell , Florida fourth-grade teacher

Jackpot! Your Union Can Help You Win Better Pay

Art Feeds the Soul… And Grows Your Union!

Get more from