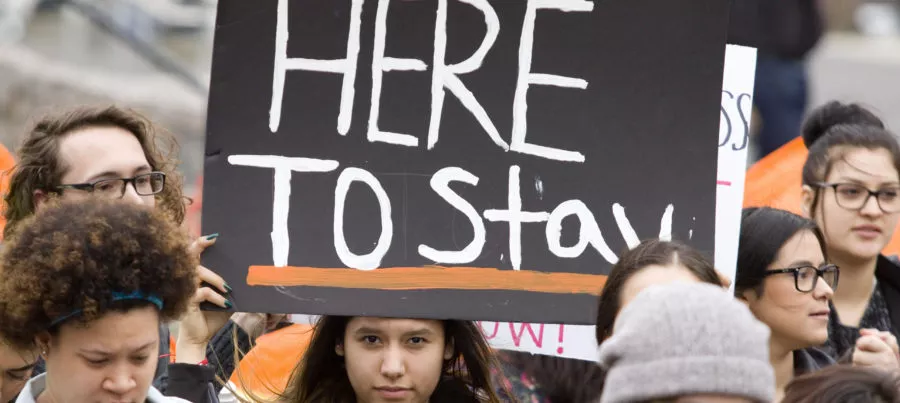

Washington State University students and community members rally in support of the DREAM Act on Thursday, Feb. 8, 2018. (Geoff Crimmins/The Moscow-Pullman Daily News via AP)

Washington State University students and community members rally in support of the DREAM Act on Thursday, Feb. 8, 2018. (Geoff Crimmins/The Moscow-Pullman Daily News via AP)

It’s been an emotional roller coaster for 800,000 Dreamers—young people brought to the U.S. as children, who have received the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, protections over the five years of the program.

In September, President Donald Trump rescinded DACA, sparking fear and uncertainty among Dreamers, including 600,000 who are high school or college students, and nearly 9,000 who are educators.

Five months later, Trump vowed to work with Congress to protect undocumented immigrants who entered the country illegally as children. “We are gonna deal with DACA with heart,” he said.

But just this month, he tweeted “DACA is dead” and “NO MORE DACA DEAL.”

“It’s hard being in this limbo,” says Karen Reyes, a 29-year-old teacher of Deaf pre-kindergartners in Austin, Texas. A former Girl Scout who has lived in the U.S. since the age of 2, Reyes attended U.S. public schools from kindergarten through graduate school, eventually earning a master’s degree in Deaf Education and Hearing Science from the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

“One moment you have your hopes up, thinking a deal might happen, and then there’s a tweet and people think you’re back to square one,” she says. But that's not the case, she explains.

"I had so many people call and text me as they heard about the tweet, asking what it meant and if we were back to square one. But they don't realize all the work that we've done, the allies we've made, and the foundation we've built. Those of us in the movement know we're not back to the beginning—we're just on a detour."

Approximately 22,000 DACA recipients have lost their status—including educators—since September. This means, they lose their work permits and the ability to teach and support themselves or their families.

“Lives are on the line,” says Andrew Kim, an immigration-rights activist who in 2015, as a student at Emory University in Atlanta, organized a successful campaign to provide need-based financial aid to undocumented students. Since then, the university has expanded their policies to include all undocumented students, not just DACA recipients.

What’s happening today, however, is more than just going to college, says Kim. “It’s about their existence because DACA affects people’s lives in every way.”

Reyes, for example, worries about having a job next school year, paying rent, and her car note. “There’s so much uncertainty,” she says.

Dreamer activists attend a press conference on Capitol Hill in September 2017 calling for passage of the Dream Act.(AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

Dreamer activists attend a press conference on Capitol Hill in September 2017 calling for passage of the Dream Act.(AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana, File)

'The Environment is Very Tense'

While fear and anxiety is mounting, especially in places like Texas and Arizona, which forces local governments and law enforcement agencies to do the work of federal immigration officers by asking residents to show proof of citizenship and where in-state tuition was dropped for Dreamers, respectively, immigration activists are busy organizing their communities.

Hugo Arreola is a campus lab technician for the Phoenix Union High School District in Arizona. A DACA recipient himself, he sees his students and community in turmoil.

“We have a lot of students on hold,” says Arreola. “Many are afraid to renew their DACA applications, student anxiety is up, and people are still scared—the environment is very tense.”

Arreola, however, isn’t idle. Through his union, the Arizona Education Association and Phoenix Union Classified Employees Association, as well as local organizations, he’s involved with various workshops, information forums, and trainings that help inform people of their rights.

"They don't realize all the work that we've done, the allies we've made, and the foundation we've built. Those of us in the movement know we're not back to the beginning—we're just on a detour." - Karen Reyes, teacher

“It starts in the local area and making sure you have representatives who understand the realities of the situation and how this impacts their area,” Arreola explains, adding that educators and community members can lobby their schools’ governing board to get friendly immigration policies passed, such as creating safe zones and protecting the rights and privacy of undocumented students.

Elizabeth Jiménez, for example, is an elementary school teacher in Westmont, Ill., and a school board member for Berwyn South 100, a district just west of Chicago with large populations of Latino, ELL, and immigrant students.

Jiménez was once undocumented herself. “I understand how it feels, however, I cannot imagine how it feels to be threatened, to be in danger of being forced to leave the only place that you know as your home … attacking our students, our neighbors, our friends and our family is un-American and immoral,” which is why she helped pass a school board resolution to create safe zones within the Berwyn school district.

The resolution passed, but more still needs to be done. “I need professional development for teachers,” says Jiménez, explaining that some teachers who don’t share the same experiences as their students don’t know what to do when parents of students get detained or deported.

Grassroots Organizing Continues

“Our fight is going to continue,” says Karen Reyes of Texas. “We still have to lobby for the Dream Act and lobby for a permanent solution because DACA was a band aid.”

Since September, Reyes has met with state and federal lawmakers. “Our biggest tool is sharing our story because once we humanize it we become more than just an acronym. I’ve met so many people who’ve said, ‘I had no idea you were undocumented.’’’ Reyes shares that many of the people who once spread anti-immigrant messages are now fighting for a permanent solution alongside her.

Additionally, the pre-kindergarten teacher has been involved with citizen drives sponsored by her local union, Education Austin, and United We Dream. “As educators we have this great niche where people trust teachers, and we can hold these trainings and reach a vast majority.”

Recently, Reyes helped organize a citizenship drive and assisted 112 permanent residents with their citizenship paperwork. “I now know there’s going to be 112 new citizens who will vote and that’s amazing,” she says.

Voting will be a critical aspect in realizing change. “We are watching,” says Elizabeth Jiménez. “Next election cycle, if you don’t support us, we’re going to campaign against you.”

Andrew Kim, originally from Georgia and currently a Ph.D. student at Northwestern University in Illinois, says the type of work Reyes, Arreola, and Jiménez do is critical and needs to be increased and sustained.

Take Action

Pledge: STAND WITH STUDENTS AND EDUCATORS TO SUPPORT DACA #DEFENDDACA #HERETOSTAY.

Policy: DOWNLOAD THIS SAMPLE SAFE ZONES SCHOOL BOARD RESOLUTION TO CREATE A POLICY FOR YOUR SCHOOL DISTRICT.

Stay Informed: DOWNLOAD THE KNOW YOUR RIGHTS (IMMIGRATION ENFORCEMENT) GUIDE.

“We’re in a dire state,” he says, and suggests volunteering or donating money to legal aid clinics, advocacy groups, or non-profit organizations that provide direct services for undocumented immigrants. Kim underscores that the efforts of everyday people need to be more than just a “one-off.”

“A drastic shift needs to happen, from a one- or two-day volunteer trip to sustained active resistance and continued solidarity with organizations that are already on the ground providing direct resources,” he says, adding that “DACA isn’t dead, but we need to support these organizations.”

Karen Reyes agrees and says, “It’s all these little steps: building up the community, building up the people power, and showing people that they do have power—just because we’re undocumented doesn’t mean we don’t have a voice. We do have a voice and it matters just as much as anyone else’s voice.”

On the national stage, NEA filed amicus briefs in two lawsuits (University of California vs. U.S. Department of Homeland Security and New York vs. Trump/Batalla Vidal v. Nielson) urging the courts to strike down the actions of the Trump Administration to end DACA.

NEA’s amicus briefs contain the voices of dozens of educators from across the country who provided a view of why DACA is important and of the impact the threat of revocation of DACA has had from the frontlines of education.

- Cindi Marten, the Superintendent of the San Diego Unified School District, noted anxiety among students transcends immigration status, “Kids are worried about what’s going to happen to them. People think this is just . . . an immigration issue. That’s not what we’re seeing. Teachers and principals are saying that kids are scared for their friends. They’re also affected.”

- Angelica Reyes, a DACA recipient and an A.P. History teacher with the Los Angeles Unified School District where she was once a student says, that thanks to DACA “I could finally serve my community. And I could be an educator. DACA gave me a clear path to obtain the career I had been working towards.”

- Kateri Simpson, a teacher in the Oakland Unified School District, has seen first-hand how DACA has motivated students to fully engage in school and work toward graduation because postgraduate opportunities like college were now within reach. Simpson says, “The basic sense of human dignity to be able to work for what you want—I don’t think can be underestimated.”

As Dreamers, educators, and families anxiously await a court decision, grassroots organizing continues around the country to pressure Congress to act.