How can we initiate discussions with our students about violence in the headlines? How can we help dispel misconceptions often passed from the adult world down to children? How can we help increase acceptance and tolerance?

How can we initiate discussions with our students about violence in the headlines? How can we help dispel misconceptions often passed from the adult world down to children? How can we help increase acceptance and tolerance?

With books!

That was the message of a panel of some of America’s most popular children’s authors during the Virginia Children’s Book Festival in Farmville, Virginia, last week. The panel, Civil Rights in Children’s Literature -- which included writers Greg Neri, Lulu Delacre, Rita Williams-Garcia, Sharon Flake, Neal Shusterman, Lamar Giles, Tim Tingle and Quraysh Ali Lansana -- was held at Farmville’s Moton Museum, the former all-black Robert Russa Moton High School and the birthplace of America’s student Civil Rights movement.

“The struggle for civil rights isn’t something that just started midway through the century, and clearly isn’t over in this one,” said Heather Maury, Youth Services Director at the Appomattox Regional Library System, who moderated the panel. “Reading about civil rights issues of the past can better prepare kids to deal with the civil rights issues of the present and future.”

Diverse books go hand in hand with issues of civil rights, and Maury says diverse books can be a safe way for children to explore difficult topics, empower them to form their own opinions, and help children who feel different to not feel so alone.

She kicked off the discussion by pointing out how difficult it is to shield children from the atrocities happening around the world and asking how young is too young to learn and talk about such events.

“I write for many ages, but my sweet spot is middle school,” said Greg Neri, a Coretta Scott King honor-award winning author of teen, young adult and middle grade fiction, including Ghetto Cowboy and the recent Tru and Nelle. “I write books that deal with serious topics like gang violence, poverty and other difficult issues facing the inner city, and when I do school visits the kids get into the topics pretty deeply pretty quickly, sometimes even as young as grade four. I find that they have no problem going there.”

Rita Williams-Garcia, winner of the Newbery Honor Award and two-time winner of the Coretta Scott King award, spoke about her book No Laughter Here, which deals with the extremely sensitive topic of female genital mutilation. She said people often assume it would only be appropriate for students ages 14 or 15 and up, but it’s actually about two 10-year-old girls and the tone of the book is appropriate for grades five through eight.

There are no gatekeepers when it comes to things like TV and video games, but there are gatekeepers for literature – they’re called teachers and librarians” - Neal Shusterman, author

“Here’s the thing that’s wonderful about young people,” she said. “They are curious about the world that they live in, and very interested. How do they react to the parts we might find horrific? They knew it was bad, but what they connected to is that there are children their age who don’t have the right to their own bodies… Sometimes we have to trust the willingness of children to learn and tell us what they are ready for.”

That’s where teachers and librarians come in, says Neal Shusterman, the author of many novels for young adults, including Unwind, which was an ALA Best Book for Young Adults and a Quick Pick for Reluctant Young Readers, and Downsiders, which was nominated for twelve state reading awards.

“There are no gatekeepers when it comes to things like TV and video games, but there are gatekeepers for literature – they’re called teachers and librarians,” he said, adding that anyone who advocates for banning books and not trusting the instincts of teachers and librarians is “doing them a great disrespect.”

Lulu Delacre, author of 36 children’s books and three-time Pura Belpré Award honoree, agreed that teachers and librarians play a key role in selecting books for children, and that they “are walking a tightrope to balance protection and freedom.”

“We want to offer literature to a child but it must be offered in a way that the child can receive it, internalize it and grow from it,” she said.

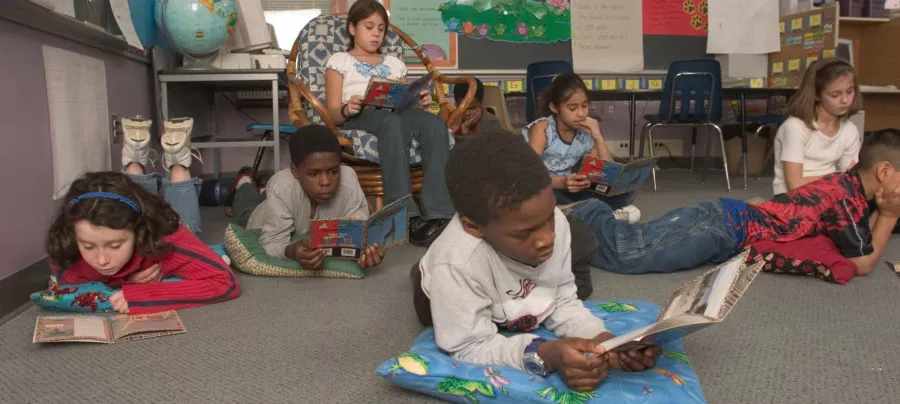

Popular authors discuss civil rights in children’s literature at the Virginia Children’s Book Festival in Farmville, Virginia.

Popular authors discuss civil rights in children’s literature at the Virginia Children’s Book Festival in Farmville, Virginia.

Books Can Be Mirrors and Windows

Maury then moved on to the subject of books serving as both a mirror and a window for young readers so that they can see themselves but also look into other people’s lives.

Lamar Giles, author of Edgar Award Nominee Fake ID and one of the founders of the #weneeddiversebooks movement, said all children need to see themselves in books, but that overwhelming majority of children’s literature features white characters. Children of color are even more likely to see books about animals or about trains or other inanimate objects than about themselves, which is why the #weneeddiversebooks movement was started.

Children’s Literature Webinar Series: Using Literature to Expand Learning October 27, 2016 | 7:00 p.m. – 8:00 p.m. (EDT)

Register to hear and speak to Margarita Engle, presenting her book "Drum Dream Girl: How One Girl’s Courage Changed Music " on October 27, 7-8 PM EDT. Also presenting a lesson to be used with the book is NEA Member and Classroom Teacher Angela Der Ramos. The NEA Teacher Quality Department and Houghton Mifflin Harcourt will host an author’s webinar on October 27. Teachers must register in order to sign and participate. Available for download will be instructional resources for teachers to use in the classroom. Classroom book sets will be raffled off! Register Now!

Lulu Delaclare said it was very hard to find diversity in children’s publishing before #weneeddiversebooks and that there is still a long way to go, pointing out that 79 percent of people who publish children’s books are white, 78 percent are women, 92 percent are nondisabled, and 88 percent are heterosexual.

“My own daughter is lesbian and parenting her was very hard. I didn’t have books for myself, let alone for her,” she said. “We need to see everybody in books, people who are like us and that open the eyes to the other, which is not the other but is a friend. We are all humans, and we are not just Native American or Latino or African American. We all share the same dreams and are all connected in the end.”

Civil Rights and Diversity

Maury then asked the panelists how civil rights differs from diversity or if they differ at all when it comes to children’s literature.

“I think diversity is an expression of civil rights,” said Neal Shusterman. “When there’s a lack of diversity, that’s an indication of an issue of civil rights.”

Lamar Giles said that as a black male he is always trying to portray black people as heroes, not only so young people can see more diversity in literature’s heroes, but because of civil rights.

“There is a direct line between the police brutality we’ve witnessed and the portrayal of black men as monsters, which is a stereotype we are used to seeing from time of slavery,” he said. “There is a direct line between how black men are portrayed and how they are treated, and I want to counteract that idea of the thug or gangster. I’ve seen so little of it throughout my own life, but now I have a platform."

Words of Hope

Maury ended the panel by asking how civil rights informs their literature and how they offer hope through their words.

We need to see everybody in books, people who are like us and that open the eyes to the other, which is not the other but is a friend. We are all humans, and we are not just Native American or Latino or African American" - Lulu Delaclare

Tim Tingle, on Oklahoma Choctaw whose great-great grandfather walked the Trail of Tears, is the author of many award-winning children’s books about the Native American experience. “I tell the truth through tragedy and then end with hope,” he said.

Sharon Flake, author of the acclaimed The Skin I’m In, said she offers hope by showing young people that they are not alone.

Quraysh Ali Lansana said that because he is a student of history, he approaches a story or poem in a moment in history and then makes a connection to the present. “There may not be overt hope, but there is change and there is growth, and in that there is some light.”

Rita Williams-Garcia believes in the small ripples of small moments, like when you say hello to someone you might not have said hello to before because you’ve found commonality with other people through reading.

Allegorical connections is what Neal Shusterman strives for.

“When I bring different ethnicities into book, or different sexual orientations, there is no attention called to it. This character is gay, that’s not a problem, it’s a nonissue,” he says. “In this world, there is no inequality. We are all equal in a story.”