The Amherst Education Association’s two-year push to ensure safe drinking water across their New Hampshire district started when President Larry Ballard asked, “When was the last time anyone checked our water for lead?”

School administrators and facilities managers were at the table, but no one could remember.

It was 2016 and questions about the safety of water in our public schools were on educators’ minds as a water crisis was unfolding in Flint, Michigan. There, pediatrician Mona Hanna-Attisha documented a spike in children’s lead levels following a switch in the municipal water supply that officials soon discovered was unsafe but covered up.

According to a new study by the Government Accountability Office that was also prompted by the Flint crisis, only 43 percent of school districts test for lead in drinking water. About a third of districts that do test reported elevated lead levels.

That means tens of millions of students and educators could be exposed to lead—a proven neurotoxin that is especially devastating to children’s developing brains—through water they consume at school. Educator unions are leading the charge in many communities to demand water testing and access to the results and advocating for policies to ensure future monitoring.

“Nobody could recall if Amherst schools had conducted water tests after the schools were switched from well water to a municipal water supply,” says Ballard, a music teacher now in his 23rd year of teaching.

New Hampshire, like most states, did not have a law requiring lead testing in schools. That meant that while the water itself was tested by the public utility, no one was checking its safety as it flowed through the district’s aging buildings.

During the Flint water crisis in early 2016, elementary school teacher Darlene McClendon delivered bottled water to her students. (Photo by Jose Juarez)

During the Flint water crisis in early 2016, elementary school teacher Darlene McClendon delivered bottled water to her students. (Photo by Jose Juarez)

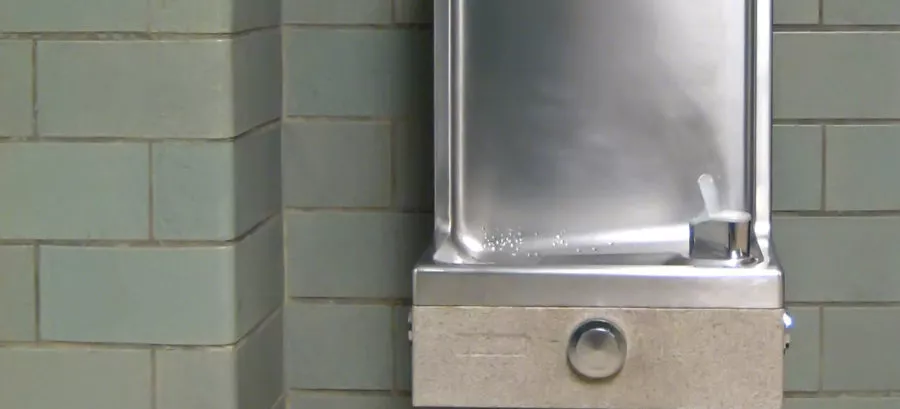

An initial round of testing ordered by the superintendent revealed a few serious problems—but information was not shared. An elementary school water fountain was shut down, but no one was told that the water it dispensed tested 100 times the EPA lead limit.

The Amherst Education Association would press for months to gain access to the results, and expand the testing to other schools.

“It just took a lot of work for us to get the district to do all of the testing that was clearly needed, and we felt they could have been more transparent about the results at the outset,” Ballard says.

‘They Came to Us Instead’

In Portland, Oregon, lack of transparency was an even greater problem. “Our school district knew that there was lead in our water, and they didn’t act upon that information in even the most basic ways, beginning with letting people know,” says Suzanne Cohen, a middle school teacher and president of the Portland Association of Teachers.

Once the truth came out in early 2016, the union stepped up to get answers for outraged educators and panicked parents. Could they send their kids to school once the water was shut off? Should they have their blood tested for lead? Why hadn’t they been informed when lead was found in 47 sites back in 2010?

“This was pretty much the lowest moment in Portland Public Schools history in terms of trust,” says Cohen. “Families and educators could not go to the district for reliable information, so they came to us instead.”

“Nobody could recall if Amherst schools had conducted water tests after the schools were switched from well water to a municipal water supply,” says music teacher Larry Ballard.

“Nobody could recall if Amherst schools had conducted water tests after the schools were switched from well water to a municipal water supply,” says music teacher Larry Ballard.

Next, the local advocated to make sure that the district would reimburse educators who wanted their blood tested. Several students would discover they had elevated lead levels.

Water fountains and cafeteria water supplies would remain shut off across Portland Public’s 90 school buildings for more than two years, during which time students and educators made do with prepackaged foods and bottled water.

The Oregon Education Association pressed for policy changes that the state would adopt, including regular water testing. OEA also teamed up with Oregon PTA and Children First for Oregon to call on the state to address the $7.6 billion in deferred maintenance desperately needed across the state’s public schools.

“Oregon has one of the lowest corporate tax rates in the nation, and some of the lowest per pupil spending,” explains Cohen. “What we are dealing with is schools that are terribly underfunded, and ours is a district that gave up on facilities maintenance to keep educators in the classroom.”

The local’s Social Justice and Community Outreach committee worked quickly to revise a bond issue to include school health and safety, which Portland voters passed in May 2017. The district has announced that it will re-open this year with all fountains and faucets turned on.

What Underfunding Means for Student Health

The New Jersey Education Association (NJEA) has made progress in ensuring water safety as part of Healthy Schools Now, a coalition that lobbied the state Department of Education to issue regulations requiring lead testing in 2017. The coalition is still working to get a law passed to make that requirement permanent.

Mike Rollins, who heads up NJEA’s Worksite Safety and Health Committee, helps locals establish their own health and safety committees to serve as “watchdogs” not only to ensure regular water monitoring, but other facilities issues as well.

“We train them to oversee what materials are being used during construction, for example, and what chemicals are used around the campus,” Rollins says. “The idea is for the local to collaborate with administrators. It’s not a ‘gotcha’ situation, it’s a chance to improve the environment for the educators and for the kids.”

Larry Ballard says the superintendent was very responsive to the Amherst Education Association’s requests for future monitoring, establishing an air and water quality testing schedule in all school buildings. During contract negotiations the local association was able to write a requirement into their collective bargaining agreement that the union will receive copies of all testing results within 10 days of receipt.

This spring, Amherst School District voters approved a ballot article for a $310,000 project to replace pipes in a middle school building constructed with solder containing an average of 54 percent lead.

New Hampshire has also passed a law that will soon require universal water testing in all schools, joining eight other states with similar laws.

“Our buildings are older and we’re going to see a lot of school districts discover that they have some pretty big issues,” Ballard predicts.

Although there is no federal law that requires states test school drinking water for lead, the GAO report strongly recommends that federal agencies, including the EPA and Department of Education, should update their guidance on lead testing and remediation, and make those resources more readily available to districts.

Federal investment in school infrastructure would go a long way in ensuring that states can efficiently investigate and address health and safety issues that include lead.

“As a community and an entire nation we need to understand what underfunding schools can mean,” says Suzanne Cohen.

“It’s not just things you can see and quickly understand, like how big is my class, what curriculum do I have, how long is my school year. It includes every aspect of students’ learning conditions from the air they breathe to the water they’re drinking.”