Key Takeaways

- Because of Iowa's law, books ranging from Alice Walker's "The Color Purple" to a biography of U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg have been banned.

- Books like these are windows and doors into other worlds—and a few politicians shouldn't be able to close them for everybody, say Iowa educators.

- In his ruling, the judge said the law is "unlikely to satisfy the First Amendment." Still, many states are embracing teacher-censorship laws.

Not long ago, a middle-school student walked into Iowa teacher Alyson Browder’s English classroom, lowered their voice, and said: “I heard you have…[pause]…LGBTQ books?”

“And I said, ‘yep, what letter do you want?’” Browder recalls.

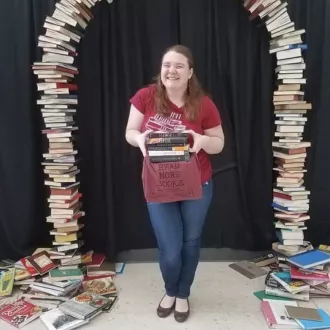

Browder has 1,749 books in her room—ranging from non-fiction to fantasy, reflecting the diversity and dreams of all kinds of students—and the thought of removing even one because of some politician’s hatred of gay people makes her heart hurt. Not only do these books inspire and satisfy her students’ love of reading, they’re essential to their wellbeing.

That’s why, in late 2023, Browder joined her union, the Iowa State Education Association (ISEA), as a plaintiff in a federal lawsuit seeking to block provisions of a new state law that bans books in K-12 schools. Other plaintiffs include Penguin Random House; ISEA members and educators Dan Gutmann and Mari Butler-Abry; an Iowa parent and a high school student; and four bestselling authors: Laurie Halse Anderson, John Green, Malinda Lo, and Jodi Picoult, whose books have been banned or removed from Iowa school shelves.

“I just really care about my students and their safety, and this law is hurting them in so many ways,” says Browder.

Recently, the plaintiffs achieved initial, encouraging success. In late December, U.S. District Judge Stephen Locher granted an injunction in ISEA’s case, temporarily blocking the Iowa book bans. The new law is “incredibly broad” and “unlikely to satisfy the First Amendment under any standard of scrutiny,” he wrote.

Locher also noted that, because of the law, hundreds of books have been taken away from Iowa students, including “nonfiction history books, classic works of fiction, Pulitzer Prize winning contemporary novels, books that regularly appear on Advanced Placement exams, and even books designed to help students avoid being victimized by sexual assault.” Meanwhile, “the Court has been unable to locate a single case upholding the constitutionality of a school library restriction even remotely similar to Senate File 496.”

Quote byAlyson Browder , 7th grade English teacher, Norwalk, Iowa

The Iowa Bans

The law, called Senate File 496 (SF 496) and enacted in May 2023, bans books describing any description of sex—regardless of context—on school shelves from kindergarten through 12th grade. It also bans books relating in any way to gender identity or sexual orientation, for kindergartners through 6th graders. (For example, To Night Owl from Dogfish, a middle-grade book by Holly Goldberg Sloan and Meg Wolitzer that centers on two 12-year-old girls’ summer camp adventures was banned because the characters have gay dads.)

Both bans encompass fiction and non-fiction. And, until last month’s injunction, Iowa educators who violated the bans could have lost their teaching licenses—and careers.

Books like Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, and Richard Wright’s Native Son have been pulled from Iowa school shelves. So has George Orwell’s Animal Farm; the Holocaust memoir Maus by Art Spiegelmen; Laurie Halse Anderson's Speak about surviving sexual assault; George Johnson’s All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir that describes his experience with anti-gay bullying; and bestsellers like John Green’s popular Looking for Alaska and Stephanie Meyer’s vampire blockbuster Twilight.

Author Laurie Halse Anderson; On Why She Wrote "Speak"

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Books like these are windows and doors into other worlds—and a few people shouldn’t be able to close them for everybody, says Butler-Abry, a high school librarian in Perry, Iowa. [In January, Butler-Abry's school experienced a deadly school shooting, in which a 17-year-old shot to death an 11-year-old and wounded seven others, before killing himself.] “We’re not talking about giving kids access to pornography. We’re talking about giving them literature—award-winning literature. That’s what kids are missing out on—just regular books—and it’s not okay,” she says.

No longer could Iowa teachers and librarians choose the books that make the most sense for their students, even though they’re skilled professionals, “trained in what is age-relevant, [developmentally appropriate], and essential to include in our classrooms and on our shelves,” says ISEA President Mike Beranek. Instead, a few politicians would make those choices for everybody, based on their own personal politics.

Quote byMari Butler-Abry , High school librarian, Perry, Iowa

Anti-Gay Animus

Gutmann, an elementary teacher and one of the plaintiffs in ISEA’s lawsuit, was 12 when his mother died. He found solace on school library shelves, where book characters who suffered similar traumas modeled resiliency. Reading stories like his made him feel less alone and helped him process his grief, he says.

Gutmann also recalls what it was like to grow up as a gay kid in the 80s. His classmates used to play a version of tag at recess, called AIDS. “If they touched you, you were the f** and you died,” he recalls. Back then, when a Des Moines school board member revealed he was gay, he needed to wear a bulletproof vest to meetings—and lost his seat in a landslide.

If Gutmann would have had the opportunity to read books with gay characters—like the middle-school kid who chastely kisses his crush in Raina Telgemeier’s bubbly graphic novel Drama—he might have been a happier kid, he says. He might not have experienced the emotional pain of hiding his identity for decades. “I like where I’m at right now,” says Gutmann, “but I do believe if there had been more positive representations in my life, I wouldn’t have spent so much time in the closet.”

Author Malinda Ko: On Why She Joined the ISEA Lawsuit

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00As mental-health issues multiply among students, the removal of books with LGBTQ characters feels like a life-or-death issue to many Iowa educators. In 2022, 44 percent of LGBTQ youth in Iowa seriously considered suicide; nearly 90 percent said “recent politics affected their wellbeing,” according to a recent Trevor Project survey.

“I had a kid literally write me a letter saying, ‘your classroom library and your safe space saved my life,’” says Browder. “You can’t tell not to save kids’ lives!”

And the benefits of diverse literature aren’t exclusive to gay kids, educators point out. Today, as Americans struggle to come together, diverse books help all people to see and respect each other, Gutmann says. “If we want to solve more of our problems in this country, we need to have an awareness of where other people are coming from,” he says. “Having diverse literature prepares students to interact in a positive way with people.”

Recently, Gutmann was wrongly told not to mention his husband’s name at school, and he no longer displays family photos on his classroom desk. Thanks to some Iowa politicians, the anti-gay animus of the last century feels present again. “The message has been loud and clear to queer families, students, and educators, we’re not so welcome in our schools,” says Gutmann. The book Drama? Banned in at least four Iowa districts, according to the Des Moines Register.

The Invisible Line

Of course, it’s not just Iowa. Last school year, respected Georgia teacher Katie Rinderle was fired by suburban Cobb County school board members for reading aloud My Shadow is Purple, a picture book that she bought at her school’s Scholastic book fair.

The text violated the state’s “divisive concepts” law, school board members said, as the book’s narrator says, “my dad has a shadow as blue as a berry,” while Mum’s is “pink as a blossoming cherry,” and “mine is quite different. It’s both and none.” The message? It’s about “finding value in [ourselves],” which is a valuable lesson for gifted children, who often can be socially ostracized, says Rinderle.

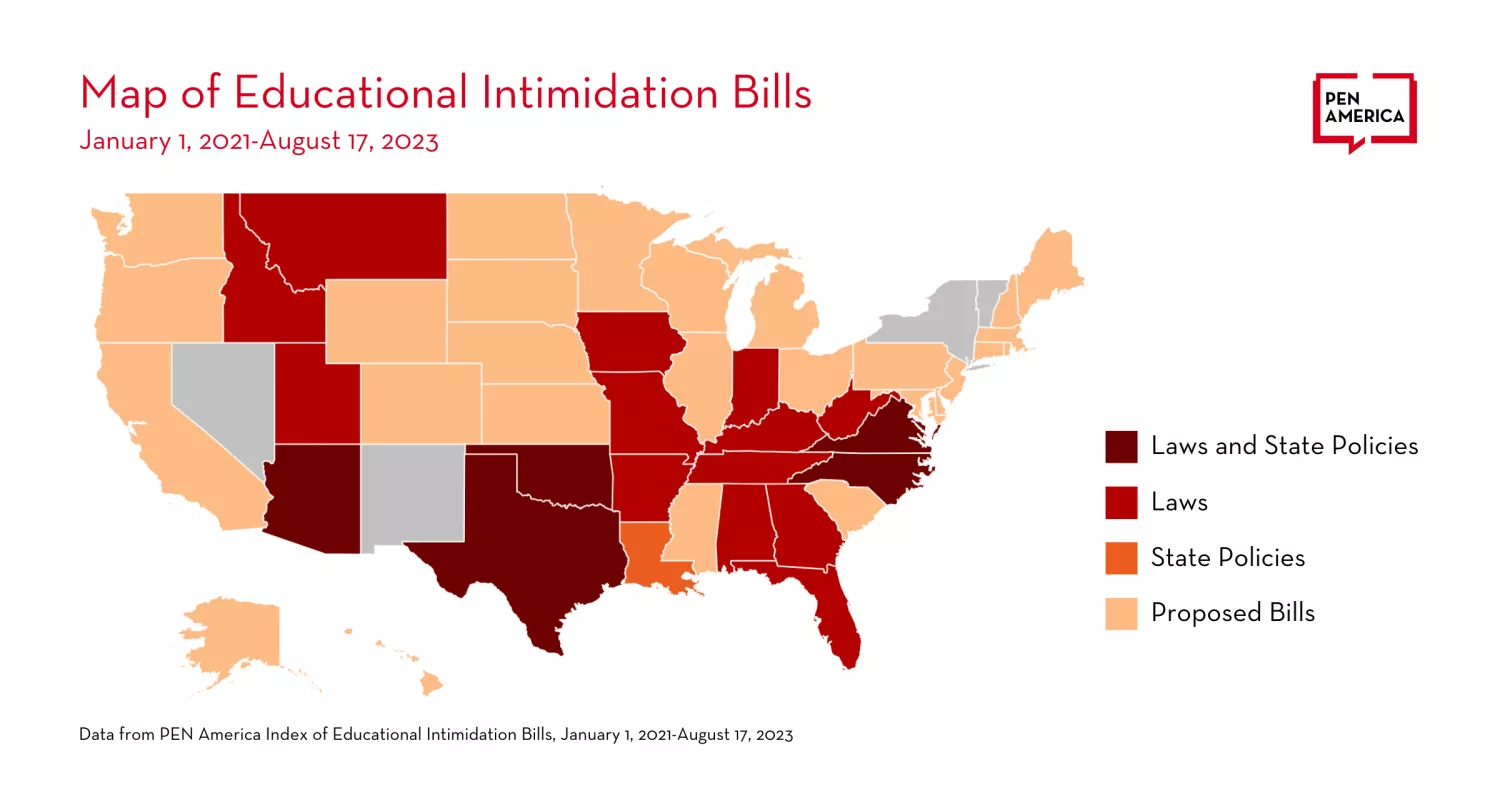

Since 2021, 16 states have passed laws restricting discussion of LGBTQ+ people or issues, according to the Movement Advancement Project. Seven explicitly prohibit it: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Indiana, Iowa, Indiana and North Carolina. PEN America calls these types of laws “educational intimidation” bills, which “empower an ideological assault on public education while effectively disempowering other parents.”

One thing all of these bills have in common? They’re intentionally vague, union members say. In Iowa, for example, SF 496 prohibits mention of sexual orientation: does that include heterosexual relationships? Would teaching Romeo and Juliet violate the law? Many educators aren’t sure what will get them fired. Consequently, they tread an invisible line in fear, self-censoring their classroom conversations and curricula.

“There’s a lot of silent censorship happening, [librarians] saying they won’t buy something because it might violate the law,” says Butler-Abry. “My school district has tried really hard to preserve students’ rights in the midst of this craziness, but others have erred on the side of caution and taken out way more than they should have. And their explanation is that ‘we don’t know.’”

Indeed, when the school year started in Urbandale, Iowa, the district office gave teachers and librarians a list of 382 books to remove. They included classics like I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou and Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret by Judy Blume, plus a biography of U.S. Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, who is married to a man. After educators complained, school officials took another look—and the list of 382 was shortened to 65.

“This is not the Iowa way,” says Butler-Abry. Not only was the state the third in the U.S. to legalize same-sex marriage, it also is home to the Library Bill of Rights, which was adopted by the American Library Association for national usage. “Our roots are centered on the freedom to speak and read,” she says.

Suggested Further Reading