In November 2016, Massachusetts voters rejected Question 2, a ballot referendum financed by the charter school industry to raise the cap on charter school expansion. The vote, 62 percent to 38 percent, wasn't close, sending a clear signal across the state that public education wasn't for sale.

In November 2016, Massachusetts voters rejected Question 2, a ballot referendum financed by the charter school industry to raise the cap on charter school expansion. The vote, 62 percent to 38 percent, wasn't close, sending a clear signal across the state that public education wasn't for sale.

To the surprise of ... well, no one, school privatization advocates didn't get the message. Charter school CEOs and their allies licked their wounds and regrouped. An opportunity soon presented itself in New Bedford, Mass., where a 2018 proposal to expand one charter school soon morphed into a transparent scheme to pry open the door to a statewide expansion.

“It was an attempted end run around the will of voters,” said Merrie Najimy, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association. “But our members and the alliances were at the ready.”

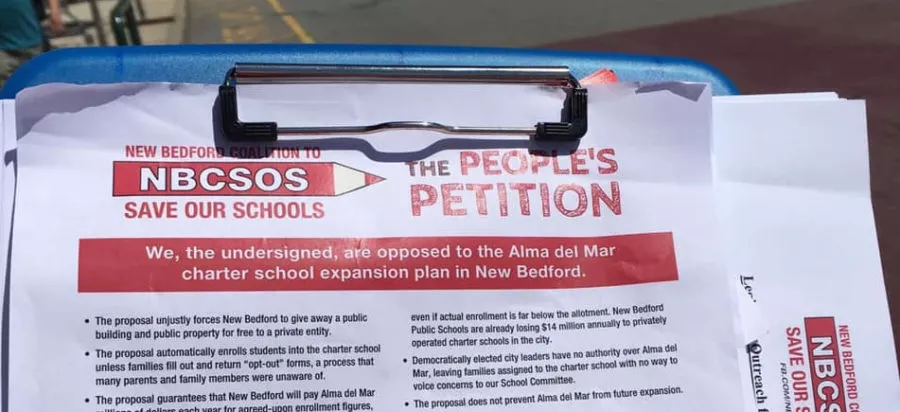

Educators and parents launched an unrelenting campaign against a proposal they believed was tantamount to extortion. By May 2019, the plan had stalled in the legislature and charter school advocates soon abandoned the effort.

The proposal—a deal brokered behind closed doors—was dangerous on many fronts. Most alarming to public school activists was the plan to carve out an attendance zone for the Alma Del Mar charter school, making it the first neighborhood charter school in the state. Students in the proposed zone would, by default, become charter school students.

"In what world is it acceptable to tell a child they have to go to a privately-run charter school?" asked State Representative Chris Hendricks.

Alma Del Mar would have been the first neighborhood charter school, but most definitely not the last, said teacher and activist Cynthia Roy.

“Those of us who could see the bigger picture knew that what was happening in New Bedford was actually a calculated step toward privatizing our schools statewide.”

Coercion, Not Innovation

The drastic underfunding of New Bedford public schools is visible to anyone who visits a campus, says New Bedford parent Ricardo Rosa.

“You would immediately see tiles hanging or falling from the ceiling. Certain schools don’t run air conditioning in classrooms or hallways. We have schools built on toxic sites...We're underfunded by about $40 million every year.”

“Those of us who could see the bigger picture knew that what was happening in New Bedford was actually a calculated step toward privatizing our schools statewide.”- Cynthia Roy, teacher and co-chair of the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools

And yet, in late 2018 lawmakers were considering a mind-boggling 1,200-seat expansion for Alma Del Mar, in a city that was already losing more than $15 million every year to charter schools.

“The financial hit this would have delivered to our schools would have been devastating,” said Rosa, co-chair of the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools (NBCSOS), a grassroots organization of families, community activists, and educators.

The coalition, which includes the Massachusetts Teachers Association and the New Bedford Education Association, helped sink the proposal soon after it was unveiled.

That wasn't the end of it. In January, a deal engineered by Education Commissioner Jeffrey Riley, Alma Del Mar CEO Will Gardner, New Bedford Mayor Jon Mitchell, and Schools Superintendent Thomas Anderson emerged from behind closed doors. Hailed as a “compromise,” the new plan would actually have a more far-reaching impact than the original expansion.

Although the number of new seats would be reduced to around 400, the new proposal would allow Alma del Mar to open a new campus at a former city elementary school property (at no cost) and enroll students within a neighborhood attendance zone, instead of using a citywide lottery. Students would automatically be enrolled in Alma Del Mar unless their parents opted out - but that would still require the approval of the superintendent.

Neighborhood Public Schools Forced to Give Up Space to Charter Schools

Neighborhood Public Schools Forced to Give Up Space to Charter Schools

In Los Angeles alone, more than 70 public schools have seen valuable learning and collaborative spaces appropriated by charter companies for their staff and students. The same trend has been underway in Chicago and New York.

Because the proposal signified a major shift in charter school policy, existing state law would have to be changed. In a dubious maneuver designed to skirt this process, sponsors presented the proposal to the state legislature in the form of a home-rule petition, setting the stage for a dangerous precedent.

“It would have allowed that substantive changes to education policy or charter school finance can be done through maneuvers which evade scrutiny, favor the charter industry, and subvert the will of the people,” said Roy.

Furthermore, if the deal was rejected, the state made it clear it would move ahead and grant Alma Del Mar a 594-seat expansion.

“The whole plan was based on coercion,” Rosa said. “This was a model for survival to skirt citizen resistance. It had nothing to do with innovation.”

Throwing Sand Into the Gears

It was clear to MTA that the charter industry was eyeing a “portfolio model” for New Bedford. A competition-based strategy championed by privatization advocates and already implemented in some cities, portfolio models carve up districts into smaller, individual “portfolios,” which are then “diversified” with more options for parents and students. Unaccountable charter schools and private schools usually flourish, while public schools are squeezed out.

As columnist Clive McFarlane wrote in May, if the New Bedford's home rule petition was approved, “you can be sure that charter school entrepreneurs will be drawn to the city like gold miners of old to San Francisco.”

Luckily, the coalition that led the charge to defeat Question 2 two years earlier was still very much intact and ready to mobilize.

“There's no question that that campaign motivated and educated parents and community members across the state,” Najimy recalled. “Everyone was ready.”

The strong partnership between MTA and NBCSOS was critical in lifting the barriers that can hamper a successful resistance.

“It was seamless because of a shared commitment to democratic principles and quality public education,” said Roy, a NBCSOS co-chair.

Coalition leaders held community forums and canvassed neighborhoods not only to engage parents and others about the dangers of the proposal and privatization in general, but also discuss what it takes to build a quality public school system.

Massachusetts Teachers Association President Merrie Najimy (center) listens to a New Bedford parent at a community forum to discuss the charter school expansion. (Photo courtesy of the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools)

Massachusetts Teachers Association President Merrie Najimy (center) listens to a New Bedford parent at a community forum to discuss the charter school expansion. (Photo courtesy of the New Bedford Coalition to Save Our Schools)

“I've never seen anything like it,” recalls Rosa. “The turnout at these events was tremendous. It was multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-generational. ...These communities were all pushing back, saying ‘no, we do not want this.’”

It was important that the coalition “moved the table,” Rosa added, so that dialogues could be held in families' homes and in their schools to include as many people in the conversation and empower them to take action.

MTA worked closely with the New Bedford Education Association to provide necessary resources on the ground and kept the pressure on wavering lawmakers in the legislature to reject the home rule petition.

In May, MTA and NBCSOS filed a lawsuit arguing that, by appropriating public money or property toward an entity that is not publicly owned and operated, the proposal violated the state constitution. The suit also charged that the proposal would “open the door wide to political abuse stripping poorer municipalities of their assets.”

Every step of the way, said Najimy, the goal was to “throw sand into the gears, and we did. And it worked.”

Indeed, by April 2019, the public confidence expressed by the plan's sponsors began to wane. The home-rule bill was on life support, and on May 31, they pulled the plug.

The demise of this particular scheme followed another setback dealt to the charter industry in Massachusetts earlier in the year. In February, educators and parents in Haverhill were successful in stopping the creation of a 240-seat Montessori charter school that would have siphoned off more than $1.6 million a year from district public schools.

With each defeat, charter industry allies grumbled in the media about lawmakers “doing the bidding” of the union and paid professional organizers - compelling evidence, said Najimy, that they have yet to grasp the growing resistance in communities to the privatization agenda.

“This proposal was defeated because of parents' activism. As a union, we used our power, but we used it to support families and communities who were vehemently opposed to a charter school expansion and model that they knew was detrimental to public schools.”