Key Takeaways

- Popular with pro-voucher politicians and policy makers, student-centered funding (SCF) would cheat Los Angeles' poorest schools of millions of dollars a year—money that they spend on academic supports, mental-health counselors and more.

- The best evidence of its failures comes from Chicago, where SCF has led to the closure of dozens of schools in Black neighborhoods. Since its implementation, the number of school librarians in the city has declined from 460 to 123.

- A far better answer for Los Angeles' students are community schools, which provide specific, tailored programs to students and families. Los Angeles educators and parents, led by their union, are "going on the offense" now.

A harmful budget proposal that would have stripped millions of dollars from some Los Angeles public schools—deepening racial and economic inequalities—was withdrawn from school board consideration this month.

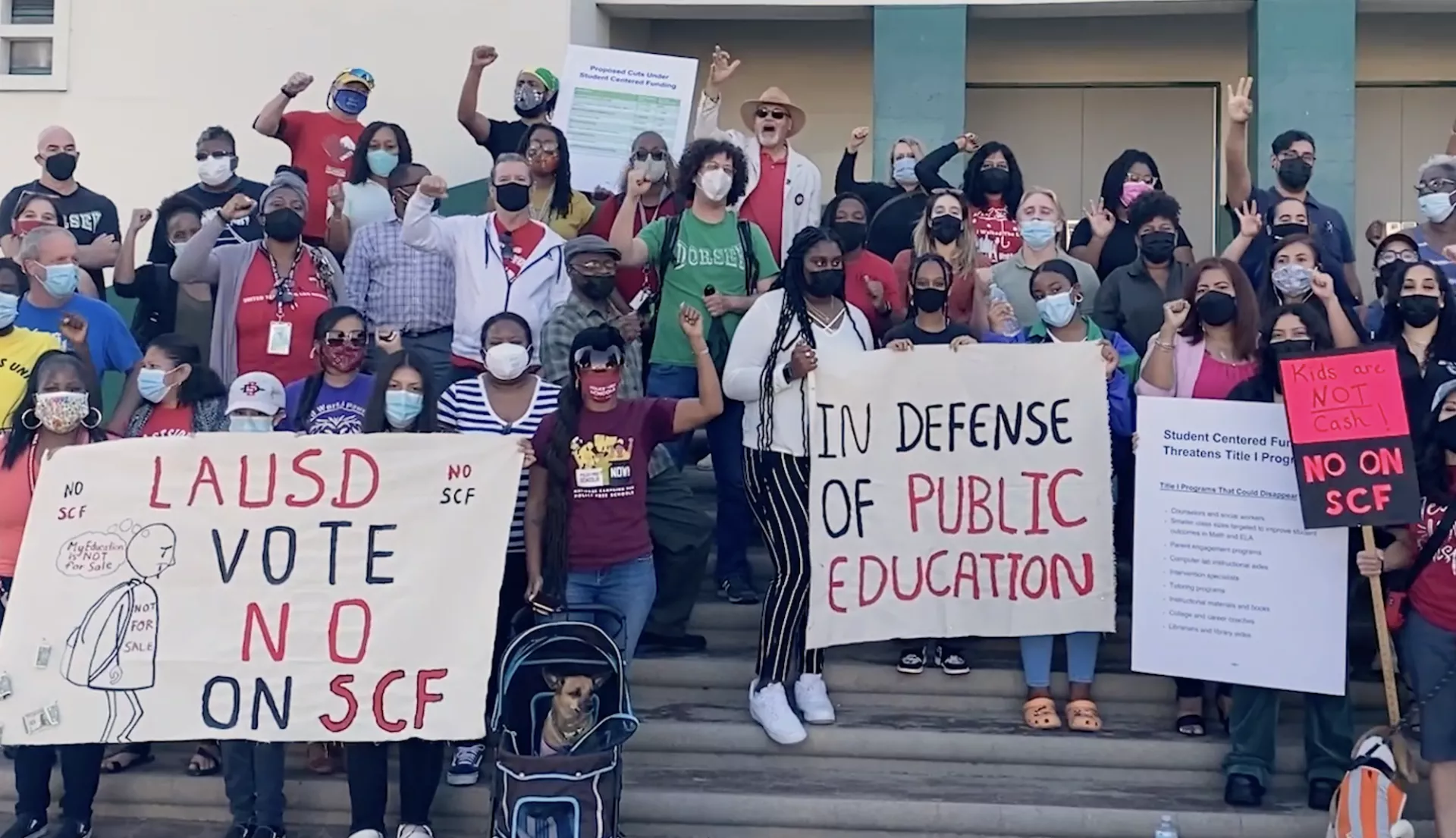

It was a “a powerful win for public education,” said United Teachers Los Angeles (UTLA) President Cecily Myart-Cruz, and it was due to the determined efforts of educators and parents who stood together.

“Your calls and emails and the vibrant community rallies … worked,” UTLA leaders told educators and parents. “The damage that [‘student-centered funding’ or SCF] would do to our schools was put front and center, and school board members noticed.”

What is Student-Centered Funding?

It may sound good, but parents and educators need only to look to Chicago to find out how bad SCF is for students, especially in schools that serve Black and brown students.

The way SCF works is, instead of funding schools according to their specific community needs, administrators divide the district’s money into per-student portions. Then, that slice of the pie follows a student to whatever public school they attend. Consequently, principals must compete for students (and money).

If this sounds familiar, notes Forbes contributor Peter Greene, a former high school teacher, it’s because “the idea of ‘the money follows the student’ is a central tenet of market-based school choice,” or school vouchers.

Indeed, it was former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos who created a federal fund to fuel SCF, while the pro-voucher, anti-public-school group ALEC has written SCF legislation. Why do they like it so much? Because it lays the groundwork for more school privatization. The very act of calculating a per-student “backpack of money” provides a gateway to vouchers.

Meanwhile, in places like Chicago, Denver and New Orleans where SCF has been put in place, it has led to cuts in arts and music programs, cuts to school librarians, nurses and mental-health counselors, and the closure of dozens of neighborhood schools, especially in low-income communities.

“It’s difficult to see how SCF can work in an underfunded district,” writes Greene. “If the pie isn’t big enough to feed everyone, no amount of creative cutting can change that.”

Lessons from Chicago

In Chicago, the number of school librarians fell from 460 in 2012 to 123 after former Mayor Rahm Emanuel implemented SCF. Vital programs like art and music have disappeared from Chicago schools, and 50 underfunded schools were forced to close their doors.

In 2019, a pair of Chicago researchers dived into the data and found that SCF deepened inequalities. Overwhelmingly, SCF led to fewer resources and smaller budgets in schools located in Chicago’s Black neighborhoods, while sending more money and resources to schools in White neighborhoods.

Chicago’s majority-Black schools—the ones that are still open—now have half as many librarians as predominantly White schools.

This approach runs opposite to the NEA mission, which strives to ensure every child gets what they need to succeed—no matter what they look like or where they live.

“We hope our findings…will help change a short-sighted policy which ignores place-based inequalities of economic and racial segregation,” said researcher Ashley Baber, who along with her colleague Ashley Farmer, called for an end to student-based budgeting in Chicago.

L.A. Educators Say No

With SCF, there are clear winners and losers. In Chicago, the clear losers are schools in Black neighborhoods. In Los Angeles, a recent analysis by UTLA and Reclaim Our Schools Los Angeles, shows how that city’s most diverse, high-needs schools also would suffer under the proposal.

For example, L.A.’s Monroe High, where 92 percent of students live below the poverty line and 20 percent are English language learners, would lose $1.25 million a year under SCF. “We have really good extra-curriculars,” Monroe student Matt Jimenez, who runs with cross-country and track and field teams. “To know that they could be cut under SCF is really upsetting,” Jimenez said, in a video statement earlier this month, urging board members to vote no on SCF.

Roosevelt High, another high-needs school in East L.A., where 99 percent of students are Hispanic and 95 percent are economically disadvantaged, would lose $1.5 million a year. Middle and elementary schools with similar demographics would lose more than $500,000 a year.

How would principals find $500,000, or $1 million, or $1.5 million dollars to cut from their budgets?

They’d be forced to do it the Chicago way—by cutting mental-health counselors and social workers, even in communities where students face frequent traumatic experiences. They’d be forced to cut librarians, arts and music programs, and after-school activities like sports and marching band that keep kids in school. Parent-participation programs. Computer lab aides. Instructional specialists.

School board members and school leaders in Los Angeles say they support equity, and say they want all students to get what they need, Los Angeles educators noted. But the Title 1 waiver on the board’s agenda on September 14 would have allowed them, if approved, to take the federal money targeted for academic, social and emotional supports in schools with high levels of student poverty and transfer it into the district’s general operating fund. Once in the general fund, it would have fueled SCF.

Led by their union, educators said absolutely not.

Going on Offense

“The students of Los Angeles deserve to attend great neighborhood public schools—places that have small class sizes, school social workers, arts and music, and all the resources necessary for our young people to grow and thrive,” said Myart-Cruz.

The answer, in many places across the U.S., is the NEA-led movement to community schools. These are public schools that provide specific supports and services tailored to their community, such as free healthy meals, dental and medical care, academic tutoring (for students and parents), mental-health services, maybe even laundry machines—before, during, and after school.

The specific programs differ from school to school because they depend on the needs of students and families, who are involved in developing the school’s programming.

Los Angeles’ Monroe High—the school that stands to lose $1.25 million a year under SCF—is one of the nation’s newest community schools.

Moving forward, the fight around SCF in Los Angeles is far from over, noted Myart-Cruz. Anti-public-school activists who favor SCF and school privatization aren’t going anywhere. They will be back.

In the meantime, educators and parents aren’t going anywhere either. In fact, after winning the withdrawal of SCF, they will be “going on the offense for authentic equity and all the resources and supports our students deserve,” she said.