Key Takeaways

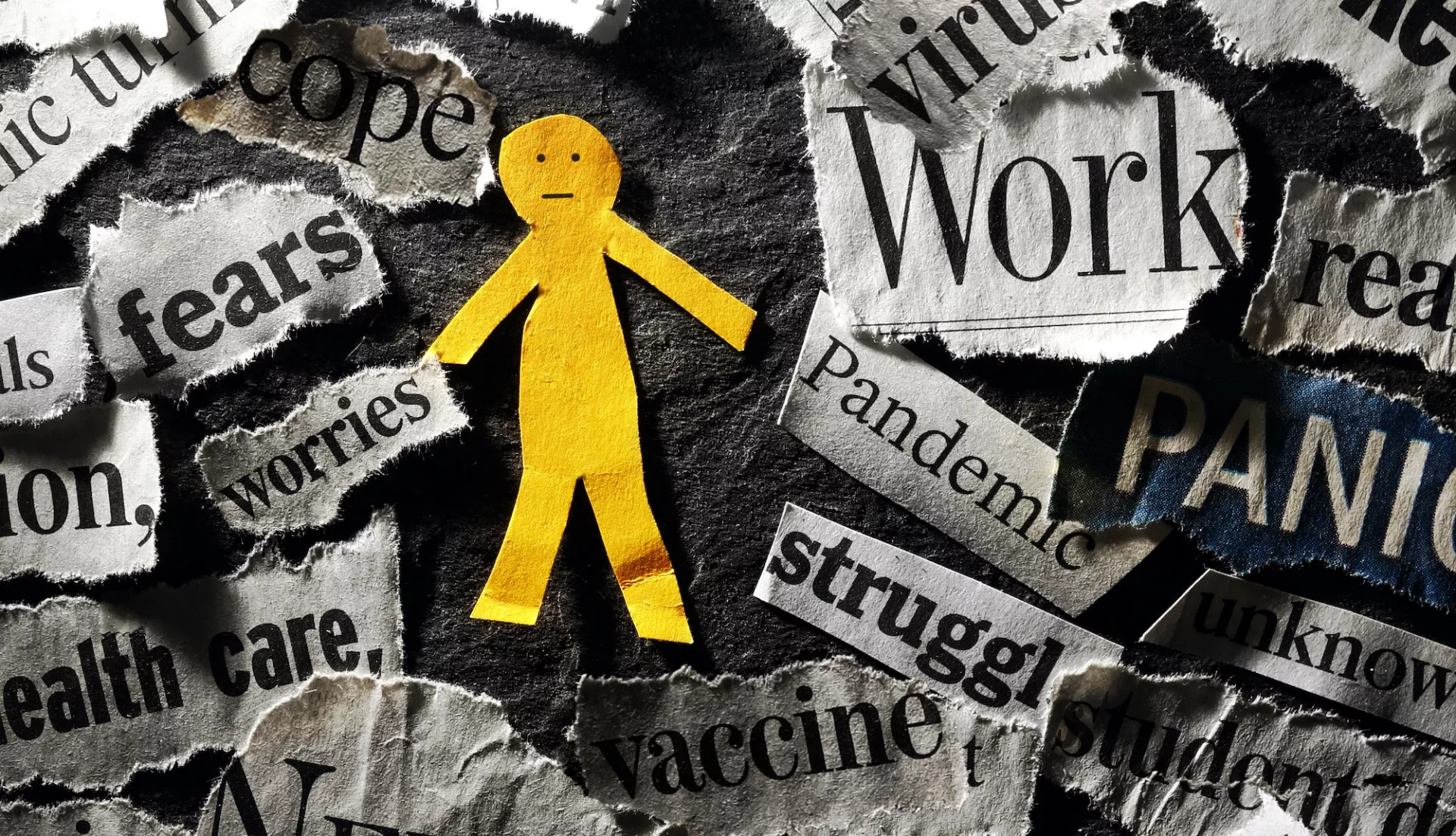

- Even in the best of times, it's really stressful to be an educator. Now, it's off the charts.

- Trainings provided by educators to educators, through their unions, are helpful. But mindfulness can't just be an extra something tacked on to the day.

- Your contract also is a mental-health tool!

How many challenges did California teacher Jesse Holmes face this fall?

Three weeks into the school year, she was reassigned from first grade to fourth, a grade she never previously taught. Not long after, her district switched from all-virtual to a hybrid model that has teachers simultaneously juggling at-home and in-person students—except when schools are closed altogether for wildfire evacuations, which also happened.

Five-minute activities now take 30. Login issues happen all the time. When lessons don’t get covered during the school day, Holmes feels obligated to create 30-minute instructional videos at night, at home, so that nobody falls behind.

Toss in a new learning management system, her role as local union rep, and oversight of the online schooling for her own three kids, ages 1 to 7—and, oh yes, a global pandemic that has killed more than 400,000 Americans.

“By November, I just wanted to be happy and I wasn’t. I wasn’t eating and I definitely wasn’t sleeping more than three hours a night,” recalls Holmes.

Even in the best of times, the life of an educator is hard on a person’s mental health. “Educators have a natural drive to care for other people, and we’re left with whatever’s left,” notes Jessica Walsh, a Delaware teacher who trains her colleagues on self-care practices.

Last year, a pre-pandemic study by English researchers found that an increasing number of teachers face mental-health issues, and that “sleeping problems, panic attacks, and anxiety issues” had contributed to teachers’ decision to leave the profession.

Now, the trauma of living through a pandemic, as well as ongoing racial and economic inequities, has deepened those issues, says Sunni Lutton, a University of Florida counselor.

Holmes reached her breaking point early this year. With her health in the balance, she forced herself to start saying no, put down her phone on weekends, and set limits on the time she spends “at work.”

Similarly, across the country, educators and their unions are developing much-needed practices and resources for mental health. Many will last long beyond the pandemic—some ingrained in personal habits, others codified into employee contracts.

“Shifting Your Mindset”

Peggy Hoy is an instructional coach and union leader from Twin Falls, Idaho, who began training her colleagues on resiliency a few years ago. “Even before the pandemic, it was like, every year, more and more things get added to teachers’ plates. We’re really good at taking things on, and really bad at letting them go,” she says.

To be the best teachers for their students, teachers first need to figure out how to take care of themselves, she says. It’s like when flight attendants tell you to put on your own emergency air mask before assisting others. “If you can’t take care of yourself, you can’t take care of the people who rely on you,” says Hoy.

This can be a difficult lesson for educators, notes Walsh, a Delaware kindergarten teacher who also does self-care trainings for colleagues. “It’s a caring profession. Through my work in education and the education associations, I spend a lot of time caring for students, whether it’s in my classroom or advocating on a larger level. I know I’m not alone in that,” she says.

But educators can't just live with the consequences. “We can’t affect our stressors, but we can change our reaction to them,” says Walsh. “It’s about shifting your mindset and the habits you incorporate daily. It’s how you live your life. Then, when the stressors come, you can manage them.”

The consequences for stressed-out educators (and their students) are dire. Toxic stress can affect every system in your body—respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrine, gastrointestinal, nervous and reproductive—as well as your ability to listen and process information. In the short term, acute stress has been shown to trigger such things as asthma, headaches, or vomiting; in the long term, it can cause chronic fatigue, depression, metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes, hypertension and cardiac disease.

Across the country, educators and their unions are developing much-needed practices and resources for mental health. Many will last long beyond the pandemic—some ingrained in personal habits, others codified into employee contracts.

Research also shows regular mindfulness practices around breathing, journaling, and more can help, although many people will need more sustained care from mental-health providers to manage their mental health.

“People really need to work on their foundations, to find out how and why they react to trauma the way they do” says Lutton. “We want a 1-2-3 solution, but it’s not. Because of the layers of trauma that saturate our society, we really need to dig deep.”

Bargaining for Educator Health

Recently, more “self-care” or mindfulness trainings have been provided to educators by their unions, like in Idaho and Delaware, but educators also have found support in contracts negotiated at the bargaining table. In Phoenix, where students and teachers have been working from home, but education support professionals in school buildings, the Phoenix Union Classified Employees Association (PUCEA) recently negotiated shift rotations for all ESPs, regardless of job category.

The union also pushed the district to hire more health and wellness coordinators, specifically for staff. “Instead of going through the Employee Assistance Program (EAP), where you have to go through the whole approval process and then only get six sessions, you’ll have somebody in-house who will just be a phone call away. You can say, ‘hey I’m having a hard time. Can you give me some strategies now to get through the day?’” says PUCEA President Vanessa Jimenez.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the union was making slow progress on these issues, says Jimenez. The new attention to staff’s health is one good thing to come out of the pandemic, she says.

In Idaho, Hoy’s union bargained for release time that provides educators with an opportunity to do their work—away from students—and a system that rewards educators with days off when they substitute for absent teachers. Both help to manage stress and workload. Additionally, sick leave policies now allow for mental-health days.

This is about doing what’s best for educators’ health, but also what’s best for student learning, says Hoy. “I really, really think to be 100 percent present for your students, you have to be 100 percent present for yourself,” she says.

For Holmes, her contract is a reminder that she is paid to work 6.5 hours a day, five days a week. Since the fall, she has set some personal limits on her use of technology outside the work day. “I have had to learn to tell myself no. And it’s really hard,” says Holmes.

But, she says, it’s also really healthy.