Inside Oregon teacher Angela Adzima’s house, kindergarten takes place in a corner of the living room. High school, for her 17-year-old son, is downstairs in the basement, while middle school ranges across the dining-room table, a space staked out by her 13-year-old. Down the hall, her husband has a spare bedroom/office.

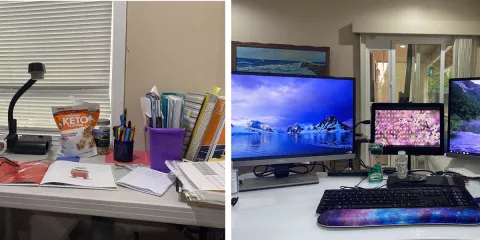

“It’s actually going pretty well!” says Adzima, whose ad hoc office features a Costco folding table and sit-and-stand desk with three computer screens, a whiteboard behind her, and a bag of Keto snacks within reach. Across the U.S., as students from kindergarten through college engage in remote learning for safety reasons, educators and parents are installing desks, upgrading home modems, and buying earphones, printers, and more, where they have the resources to do so. But physical considerations are only part of the challenge.

For educators, it can be particularly tough to balance the newly dueling roles of online professor and parent. In second-grade teacher Trevor Wills’ Chicago home, it looks like this: “I run around the house during these few 15-minute windows in my schedule, setting up links for my daughters and I’m like, ‘Sit here and wait until your teachers come on!’”

While these educator-parents attend to the 30-plus students in their online classrooms, they often are forced to ignore the one who is knocking at the bedroom door. “I really want this to be a good experience for my students,” says Wills, who figures he has evenings and nights to go over things or re-teach to his 5- and 8-year-olds. Across the nation, a lack of available childcare—or adequate salary to pay for it—complicates matters.

An Unworkable Situation

For some educators, it’s unsustainable. In August, Los Angeles teacher Lorraine Quiñones told the Los Angeles Daily News that the stress had left her sobbing. She had spent $500 to turn her 1,300-square-foot home “into a four-room schoolhouse,” and even before school started the effort had taken an emotional toll.

This fall, educator resignations are increasing for many reasons, including safety and parenting concerns, and growing stress and mental-health burdens. Recently, Virginia assistant principal Adam Evans opted for a year off. Instead of trying to simultaneously serve the healthcare needs of his wife, who has Stage IV cancer, the educational and emotional needs of their three children who range from 3 to 8 years old, and his own professional expectations around supporting his colleagues and students, Evans decided he couldn’t do it all.

“I just realized there was no way it was going to work,” he says.

A recent study of educators in nine states found that 40 percent said a lack of childcare, or care for dependent adults, made it difficult for them to teach during the spring shutdown. Meanwhile, a NEA survey found that large percentages of teacher say the pandemic has made them more likely to retire or resign early.

This fall, with new pressure from educator unions, some school districts and institutions are working with educators to ease the childcare burden. In Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Teachers Association has rejected state guidance that would force teachers to teach from empty classrooms with their children napping on the floor, and is supporting local unions in fighting for more parent-friendly provisions. For example, in Los Angeles, a union agreement requires the district to provide childcare for teachers who must come into school. The district also has a mental-health hotline, a mental-health crisis hotline, and a COVID-10 hotline.

Meanwhile, in Florida, the United Faculty of Florida chapter at the University of Central Florida (UCF) is negotiating for increased, emergency pay.

Extra Work, Extra Costs?

For many professors, as well as K12 educators, the move to virtual learning has meant spending days or weeks in professional trainings, many more meetings with colleagues and administrators, and new, additional work in designing online lessons and group activities.

“We’ve done this extra work to the best of our abilities and we should be compensated for it,” says Beatriz Foster-Reyes, an associate professor of anthropology, vice president of the faculty union, and the mother of three, the youngest of whom is a toddler.

To get this new, additional work done, while also making sure the educational needs of her own daughters are met, UCF associate professor Brigitte Kovacevich is paying $400 a week for a part-time learning coach for her school-age daughter, while also paying to send her 2-year-old to daycare. “We’re going into debt to do this,” she says.

At the same time, because this new way of teaching is so demanding of her time, Kovacevich has suspended her anthropological research and writing, despite the potential consequences to her career advancement. Doing field research—and publishing the results in peer-reviewed journals —is a critical part of the pathway to tenure and promotion in higher education.

“We’re essentially being asked to sacrifice our own futures and finances to ensure that UCF students get a quality education,” Kovacevich says.

Will it Get Worse Before it Gets Better?

What if teacher-parents and their children aren’t even in the same district? While Wills lives in Chicago and his daughters attend Chicago Public Schools, he teaches in the suburban Bellwood district that likely will move to hybrid learning before Chicago schools.

With all these variables to consider—plus safety and financial concerns—educator-parents say this year is more stressful than any other. For Virginia’s Evans, it was just too much. A couple of weeks ago, he was working at school when his 8-year-old called and said his mom wasn’t well. A trip to the ER followed. A few days later, another call, and another, lengthier stay at the hospital. Meanwhile, he heard of a colleague who had contracted COVID-19 at work, and at home, his 8-year-old was enrolled in virtual summer school and requiring continuous support.

“What I realized was there is no way it was going to work. Somebody needs to sit with him, answer questions, get him back on line,” says Evans, who also has a kindergartner and preschooler. So, Evans now is running a learning pod with his two school-aged sons and two others. His hope is that it can be a creative learning space, heavy on the kinds of social justice and multicultural lessons that he wishes he would see more in public education.

Still, “I feel bad I’m not in the trenches with my colleagues,” he says. Nonetheless, they still have his support. “I feel like teachers are being taken advantage of, slightly. Give us the resources and funding to be effective!”