Key Takeaways

- The highest paid professor in the U.S. is likely a man, at a research university, who teaches medicine or engineering. It’s definitely not a woman, at a historically Black college, teaching education.

- The wages paid to graduate assistants are almost unlivable. Their average stipend in 2024 was about $20,000.

- Unions make a huge difference!

Last year, faculty saw a 1 percent gain in purchasing power, according to the 2025 NEA Faculty Salary Report, released this week. The problem is that such a small gain still leaves faculty feeling poorer than they were five years ago. Between 2020 and 2023, as inflation soared, faculty purchasing power declined by 7.7 percent.

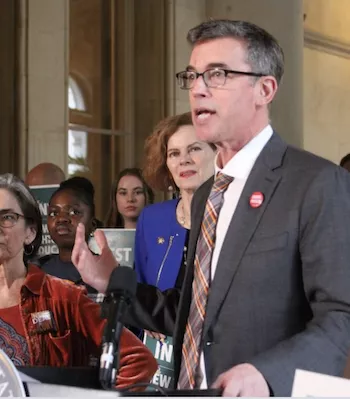

But, if that's the bad news, the report also includes good news for union members. “The big takeaway is that we do have power on these issues—and it's through collective bargaining. The power is at the table,” says Alec Thomson, a political science professor at Michigan's Schoolcraft College and president of NEA's National Council for Higher Education.

Unionized faculty who collectively bargain are paid tens of thousands of dollars more than those who don't, the new report shows. And it helps everyone around them, notes Thomson, including other staff on those campuses and even non-union faculty in the same states.

Chart 2: Heck yeah, unions make a difference!

“We have a very strong union,” notes Sara Williams, math instructor and bargaining team member at Oregon’s Mt. Hood Community College. The proof of their strength? A new 4-year contract, ratified in 2024, that provides 18 to 21 percent raises for about 150 faculty members.

It took a full two years to bargain the contract, Williams notes, and the process relied on a very experienced bargaining team and a deep bench of union members who showed up for public bargaining sessions and volunteered on support teams.

“We told faculty from the start that we were asking for a lot, and it might take a while to get it,” she says. But it would be worth it: before this contract, new faculty members couldn’t afford to rent apartments in town.

“They need to get roommates. Is that what we want? Employees who can’t even afford to live in their own places?” Williams asks. “I don’t think so.”

The bottom line is that faculty represented by unions make more money. For example, community college faculty with collectively bargained contracts made $93,000 in 2024, on average. Meanwhile, community college faculty without unions—working in the same states as unionized faculty—made $73,000. Those in states without any unions made $66,000, according to the new report.

Two contracts ago, part-time faculty at the City University of New York (CUNY) were paid a minimum of about $3,200 per 3-credit course. One contract ago, the floor reached $5,500. Today, thanks to the latest union contract, ratified in December, it’s $7,100. “That’s a lot of movement over two contracts. We’re getting to the point where the university’s incentive to abuse the adjunct system is reduced, almost to the point where I think we’re going to see more full-time hires,” says James Davis, president of the Professional Staff Congress (PSC) that represents faculty and staff across CUNY’s 25 campuses. But, he adds, “it’s still not enough.”

The PSC bargaining team worked for two years for this contract, which provided across-the-board raises of 13.4 percent, plus equity raises that reached up to 40 percent for the most underpaid union members. Their priority? Increasing pay for all members, but especially for their most underpaid. “We have a strong understanding, across the union, that when you lift the floor, everybody benefits. That’s not necessarily intuitive in a union and especially in academia, where there’s a lot of individualness,” Davis notes.

The 11,000 part-time faculty at CUNY teach the majority of classes, notes Lynne Turner, PSC vice president for part-time personnel. “Student learning depends on our skills, our expertise, our dedication… and when we’re devalued, our students are devalued. CUNY is devalued,” she notes. “We, as a union, won’t pretend that what we won is enough. But we do feel like we made major gains and we’re proud of that… Hopefully, it makes a difference in adjunct faculty having a greater level of stability.”

Chart 3 (and 4): The HBCU Pay Penalty Still Hasn't Gone Away

On average, faculty at historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) earn 75 cents to the dollar earned by other faculty, according to the new NEA report. Across different types of institutions, the disparity is worst at research universities. On average, faculty at historically Black research institutions like Florida A&M University (FAMU) and Tennessee State University earn $83,000. Other university faculty? $112,000.

“It’s like being in an emotionally abusive relationship,” says Samique March-Dallas, a finance professor and faculty union president at Florida A&M University (FAMU). “People stay at FAMU because we’re aligned to the mission and doing it for the culture. We want to see Black students succeed and we want to help. Or you’re an alum and so you want to see the school—your school—grow.”

March-Dallas notes these reasons are pervasive across all HBCUs. HBCU faculty know they’re underpaid. They also know they’re overworked. But because they care so deeply for their students, they stay and demand better. FAMU’s union has been at the bargaining table for more than 3 years, attempting to renegotiate a contract that expired in June 2022. “Yes, more than three years,” sighs March-Dallas.

FAMU is an “R2 research institution,” which is the second highest Carnegie classification and denotes significant research activity. The only other R2 institution in Florida is Florida Atlantic University (FAU). And while FAU faculty also are paid far less than the U.S. average, at every rank, they still get more than FAMU professors. Associate profs at FAU? $99,000. At FAMU? $83,600, on average.

The HBCU disparity also varies by state. In Ohio, HBCU faculty earn about half as much as other faculty. In Alabama, it’s 72 percent; in Florida, it’s 68 percent.

Chart 5: Women Faculty Still Paid Less

On average, women teaching in public colleges and universities were paid 86 cents to the dollar paid a man. The gap is smallest at community colleges, where women are paid 96 to 98 percent of men’s earnings. It’s largest at research universities, where women get just 84 percent of men’s pay.

Contributing factors likely include: first, the fact that women represent just a third of the faculty at research universities, where faculty are best paid. Second, they’re more likely to teach in academic departments that are undervalued by their bosses, like education. (See Chart 8.) And third, they’re more likely to drop out of academe before getting to the highest-paid rank of full professor.

Chart 6: Grad Students Have It Really, Really Tough

The average stipend paid to a grad assistants across the U.S. in 2024 was about $22,000, according to NEA research. At the University of Rhode Island (URI) specifically, it's about $23,000. Meanwhile, it would take more than $52,000 a year for a single adult, living in the area around URI to pay for food, medical bills, and a roof over their heads, according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator.

“A lot of people get part-time jobs, pouring beers, making coffees. Obviously it's a lot of time taken away from their research. Others have to rely on their parents for rent assistance and help paying bills,” says Maggie Bernish, a Ph.D. student in biological oceanography, who also serves as president of the URI Graduate Assistants United (URI GAU), an NEA Higher Ed-affiliated union of grad employees.

To make ends meet, Bernish not only has worked 20 hours a week, she previously received SNAP benefits, often known as food stamps. Many of her colleagues in the URI union still do.

This spring, URI GAU is at the bargaining table, arguing for higher pay. As URI is the only public R1 institution in Rhode Island—R1 refers to the highest possible Carnegie classification for research universities—the union's leaders are looking to similar R1 public institutions in nearby states. For example, the average stipend at UMass Amherst? It's $28,000, and the cost of living there is lower. “URI just recently became an R1 institution and our pay needs to reflect that. It wouldn't have happened without the hard work of grad assistants,” says Bernish.

Since 2012, the number of grad assistants who belong to unions has increased by 133 percent. And that's no coincidence, notes NCHE's Thomson.

“Grad assistants, HBCU faculty, these are areas that are experiencing growth in collective bargaining — or calls for growth,” says Thomson, “and I think that’s the obvious solution—not just terms of pay, but in terms of power.”

Chart 7: Where You Teach Matters

Chart 8: What You Teach Matters Too

Pay is highest for university faculty who teach engineering, physical sciences, etc. It's lowest for faculty who teach future teachers and librarians. As noted above, these lower-paid fields tend to be taught by women.