Key Takeaways

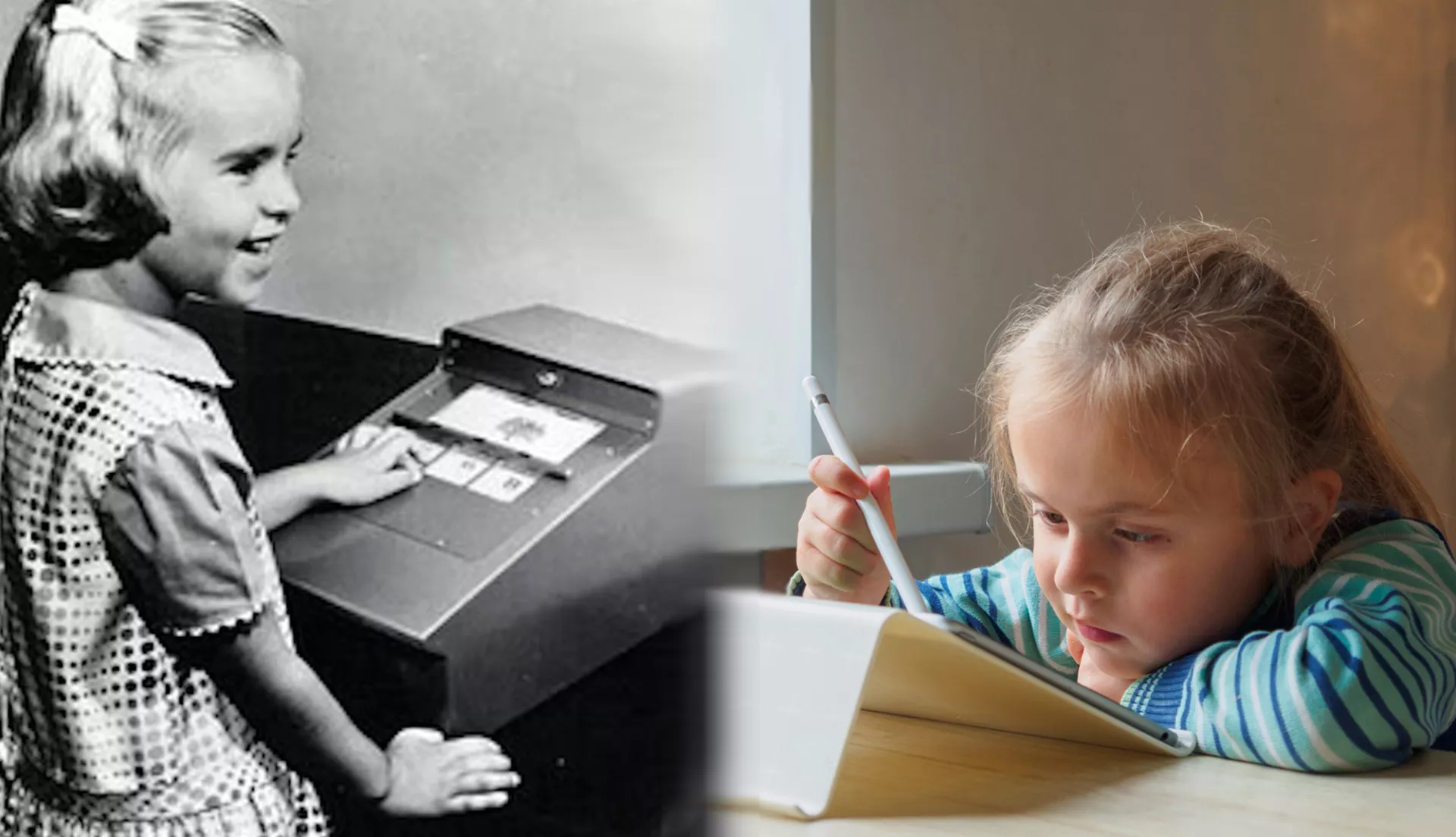

- "Personalized learning" became an ed tech catchphrase in the past decade, but the idea dates back to the early 20th century. A new book details how the invention of two "teaching machines" merged personalized learning with technology.

- The story of these early, failed attempts at commercializing programmed instruction, says author Audrey Watters, helps us understand how technology became such a massive presence in our public schools.

- Often a valuable classroom tool, technology is also used to engineer and control teaching and learning. But Watters believes educators, students and parents can and should resist the "mechanization" of public education.

The myth of the broken, unresponsive public school system has long reinforced the belief among many that whatever question you may have about improving education, technology and computerized learning is the answer.

The "promise" of ed tech as the savior of public education goes further back than you might think. Long before Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, for example, began championing and bankrolling online personalized learning in 2016, there was B.F. Skinner, a behavioral psychologist who in the 1950s invented a "teaching machine," a mechanical device designed to automate and individualize instruction so that students could learn at their own pace. Before Skinner, there was Sidney Pressey, psychology professor at Ohio State University and standardized testing pioneer, who created a "machine for intelligence testing" in the 1920s.

The ideas behind the Pressey's and Skinner's machines were based on dubious behaviorist learning theories, a misunderstanding of a teacher's role, and a profound, unshakeable conviction that they had unlocked the mystery of student motivation and learning.

That probably sounds familiar, says education and technology writer Audrey Watters. Watters is the author of a fascinating new book, "Teaching Machines: The History of Personalized Learning," which recounts how these and other early "innovations" failed to live up to their hype. And yet, as Watters describes in the book, the Pressey and Skinner machines have been hugely influential, serving as an early trial run in the push to embed computerized teaching and learning in every school. As Watters told NEA Today, maybe it's the tech industry and its followers - not the individuals who work in public schools - who have refused to change their thinking about education.

What is it about the story of Pressey, Skinner, and other early advocates of computerized instruction that resonates today?

Audrey Watters: When I was writing the book, there was this rather didactic part of me that wanted to end every paragraph with "and this is precisely what is happening today." There are these echoes for people who are familiar with education technology. Echoes of the stories that people tell, the struggles they face, the responses from students and teachers, the responses from entrepreneurs and big business, that seem to have parallels today.

I was interested in correcting this amnesia that we have – either deliberate or just forgotten history - about ed tech, in part to show what we see today is really not as new or "innovative" as some of the proponents would have us believe.

If we understand the history, we can respond better to these sales pitches. We can also understand why so many of our schools look the way they do.

These are sales pitches that, then and now, are driven largely by the 'schools are failing and incapable of changing' narrative.

AW: Right, and that narrative didn't start with "A Nation at Risk." Obviously schools can and have changed a lot in substantive ways. It's insulting to say otherwise.

The other piece of that narrative is that the education system is, to a fault, deeply standardized and we’re pushing everyone into - another cliché - a one-size-fits-all system. But we've been told that suddenly with computers, we can now personalize education. Earlier in the 20th century, they called it "individualizing" education. So, again, this is not a new idea.

Pressey in the 1920s and Skinner in the 1950s were both convinced that their teaching machines would be "game-changers" for the education system. Why did they fail to break through?

AW: Entrepreneurs or tech people will come into schools and say, “Look everyone, I’ve got a quick fix-it," but education is such a complex system. They don't understand that. Skinner did blame teacher unions for resisting change, but, again, contrary to the story that gets told, NEA was really quite supportive of all sorts of innovations in the classroom. In the mid-to-late 20th century, teachers were intrigued about how new technologies things like film and radio could be used in the classroom. So, like today, the idea back then that teachers were resistant to technology was overblown.

For Skinner and Pressey in particular, the people who stood in the way of the commercialization of their products was actually business itself, who didn't see how they could turn a profit on it.

But there was understandable resistance on the part of teachers to these machines. What were the concerns?

AW: There was a mixed response, just as there is with any kind of change in pedagogical practices or what teachers are supposed to do. It wasn't necessarily a fear that the machine was going to replace them, however. Some liked the idea of Skinner's machine, that students were supposed to work at their own pace. Others not so much. It just didn’t fit with how they taught, what they imagined their classroom to look like.

Also, in post-World War II America, teachers were seeing the size of their classes increase. With Skinner's machine, the pitch was that it would help them teach a class of 60 rather than a class of 20 or 25. So "you can now have more students, thanks to this innovation!" It's like the MOOCs [Massive Open Online Classes] today, which can help one teacher teach thousands of students.

So when they heard that Skinner's machine would facilitate many, many more students, a lot of teachers said "no, thank you."

And it's important note as well that student's weren't thrilled either. The Ohio State students who responded to Pressey's machine said it did nothing to reduce the drudgery of taking tests. It was cool, cutting edge technology, but after a while, it was still boring.

Ed tech can usually rely on, to say the least, friendly media coverage. Was that the case in the 1950s?

AW: Absolutely. It was fascinating to go through the newspapers from that period and recognize that the same schools were highlighted again and again. It was the same principal who would get quoted again and again. When you look at the coverage of ed tech today, you'll also see the same schools getting highlighted, the same people journalists turn to over and over for a quote about the wonders of technology.

So the media certainly played a huge part in, not only making it seem like teaching machines were the thing to do, but also perpetuating the larger narrative that schools were failing and something needed to be done. And that something was technology.

And anyone - educators in particular - who stood up and said not so fast was quickly branded as "anti-technology" or a "Luddite."

AW: Sure. You know, I sort of embrace the Luddite, whose story has been misunderstood. The Luddites were weavers and craftspeople who used machines to make cloth. They weren't against technology. What they were opposed to were the factories in which this kind of mechanization was taken out of their hands, the ability to make cloth was taken out of their hands.

So working with technology when you have control over what you think and what you build and what you do is very different from having your product extracted from you. So the Luddites were a good model. It wasn't "no, we don't want the machines." It was more "no, we don't want exploitive labor practices!"

Despite technology being so immersed in everyone's lives, and the soaring amount of money spend on ed tech, you still believe the "mechanization" of education is not inevitable?

AW: I hope the book shows that resistance is possible. People have always resisted technologies that they believe are degrading or antithetical to freedom. I think that's one of the things we see today, despite the story that technology overtaking schools is inevitable.

As we saw with the pandemic, it was necessary for student health and safety. But a lot of the technology still isn't very good. It's certainly not better than in-person classroom instruction.

People generally get caught up in the gadgets, and not the practices. Students aren't learning more, they aren't learning more quickly. So I think there will be quite a lot of disillusionment. We're not going to see any educational breakthroughs through this massive adoption of technology. We haven't yet.

Students, teachers and parents are raising questions - not only about pedagogy and certain types of projects they are doing in class with technology. There's online proctoring. This is a big issue because it raises questions about assessment. What does it look like? What does it have to look like? The answer should not be, "yes, it has to look this way, because the company built this incredibly expensive solution that will surveil all of your students data."

So it isn't a matter of saying "no" to technology. That oversimplifies the problem. Instead, let's say no to practices in the classroom - technological or not - that instead of engaging and supporting students’ agency and autonomy are designed to program instruction and engineer their behavior.