Pandemic Brings ‘Homework Gap’ to the Forefront

Even before the coronavirus outbreak, some 8.5 to 12 million K–12 students lacked internet access at home, making it difficult, if not impossible to complete homework assignments. This so-called “homework gap” widened as an increasing number of schools over the past decade incorporated internet-based learning into daily curriculum. The problem was exacerbated when schools closed in March due to the pandemic. During stay-at-home orders, many students were no longer able to spend time in school buildings, libraries, cafes, or friends’ houses—the places they may have accessed Wi-Fi in the past.

Those living in rural communities and students of color experience the greatest homework gap. According to a 2019 Pew Research Center report, 37 percent of rural Americans have no broadband internet service at home, trailing urban residents by 12 points and suburban resi- dents by 16 points. The Pew research shows that among families with school-age children, 25 percent of all Black households and 23 percent of Hispanic households lack high-speed internet. Only 10 percent of white households with school-age children lack internet access.

At Memorial High School in Tulsa, Okla., where Shawna Mott-Wright teaches, more than 80 percent of students are from lower-income families, and as many as half either don’t have computers or mobile de- vices, or they don’t have high-speed internet access.

“People like to talk about opportunity all the time, but I always say without access, opportunity means nothing.”

—Shawna Mott-Wright, teacher, Memorial High School, Tulsa, Oklahoma

How Student Debt is Impacting the Teacher Shortage

Public school students are more diverse than ever, but their teachers? Not so much. Even as research shows that students, especially students of color, benefit from a diverse workforce, more than 8 in 10 teachers in American public schools identify as white.

One reason—which is receiving more attention from policymakers— is the unequal amount of money that students of color, on average, must borrow to pay for college. On the day they graduate from college, Black students owe about $7,400 more than white students, according to a Brookings Institution analysis.

The Center for American Progress found that 91 percent of Black students who studied to become teachers were forced to borrow from the U.S. Department of Education

to finance their college education, compared with 76 percent of white students. Among Latino students studying to be teachers, 82 percent had to take out federal student loans. In graduate school, which may be required by states for licensure and certification, the disparity grows even larger: About half of Black teachers borrowed, compared with about one in three Latino teachers and one in four white teachers.

That kind of debt, paired with the prospect of low teacher wages and other factors, makes education an impractical choice for many Black and Latino students. Many think they simply can’t afford to be teachers.

Research shows that all students benefit from diverse teachers, but Black students specifically do better on tests, attend school more regularly, and have fewer discipline issues when they are paired with a Black teacher.

Black students also are more likely to be identified as gifted by Black teachers than by white teachers.

Parents Overwhelmingly Approve of Educators During Coronavirus

When the coronavirus pandemic forced school buildings across the country to close in March, educators reacted quickly, not only to continue students’ education, but also to help them stay fed, supported, and healthy.

It’s no surprise then that parents overwhelmingly approve of the job educators are doing.

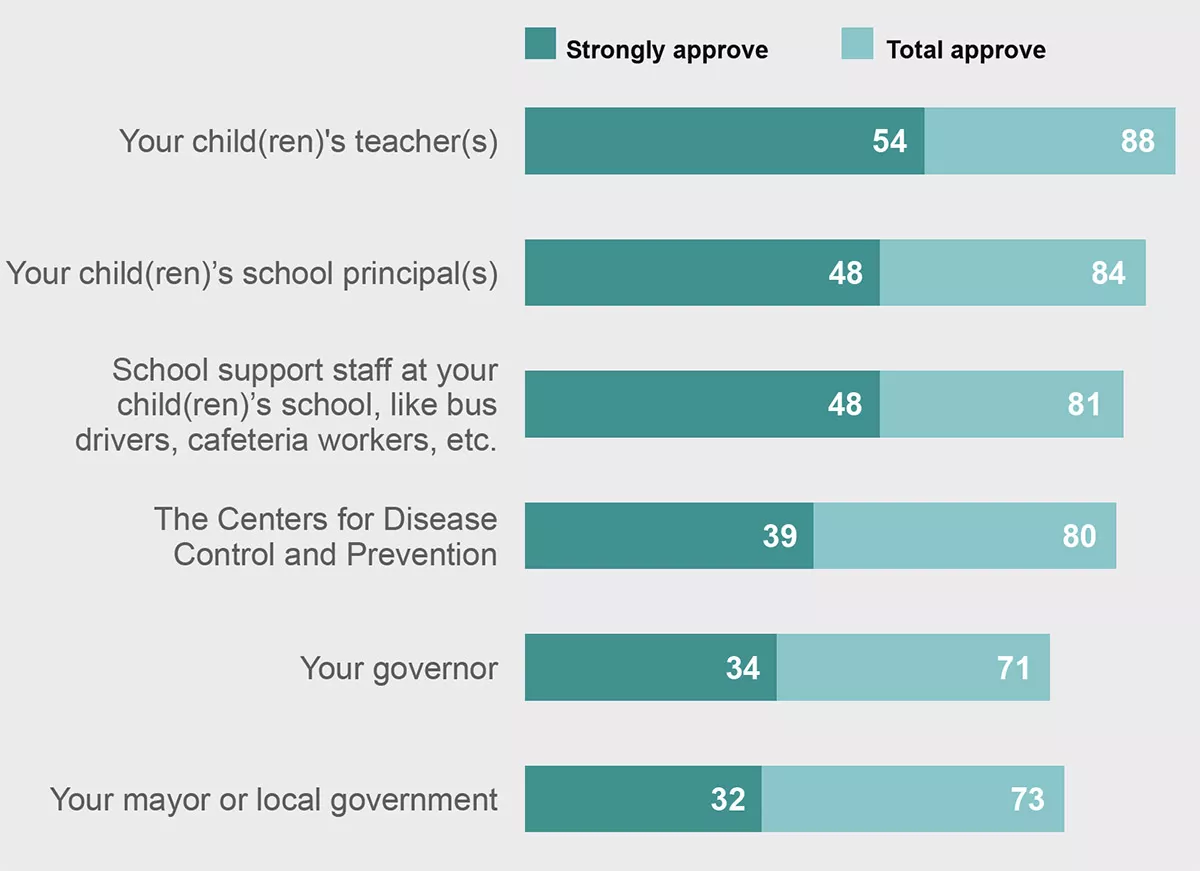

An NEA survey found that 88 percent of parents approve of how their children’s teachers are handling the coronavirus pandemic. They also overwhelmingly (81 percent) approve of school support staff (school bus drivers, cafeteria workers, etc.)—giving them a higher rating than they give to their governor and their mayor or local government.

Educators: Help Keep the Census Count Going!

It is not too late to help make sure your students and your community are counted in the U.S. Census.

The census was scheduled to close in July, but it’s been extended due to the coronavirus outbreak. Now, the web portal (2020census.gov) willstay open and the door-knocking will continue through the fall. That means you can talk to students about the census from the start of the school year and probably through October.

When you teach your students about the importance of the census, you empower them to help their families get counted.

Using census data on popula- tion and poverty levels, the federal government allocates more than $1.5 trillion in funding to states and localities annually. This includes funding for educa- tion that helps schools reduce class sizes, hire specialists, and bolster teacher quality. It also provides preschool for low- income families and ensures that hungry students can get breakfast or lunch so they can focus in class.

NEA offers a free census toolkit and online resources, including suggestions for home and distance-learning activities at nea.org/census.

100th Anniversary of Women’s Right to Vote

As we celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which guarantees women the right to vote, we celebrate the power of collective voice.

Susan B. Anthony (who was a teacher) is an icon of the early movement, but legions of lesser known suffragists were active in cities and towns across America. They took to the streets to join demonstrations, handed out pamphlets to raise awareness in their communities, and petitioned Congress. Together, their unifed voices were fnally powerful enough to affect change.

The 19th Amendment was ratifed 100 years ago this month, on August 18, 1920. Women in all U.S. states (48 at the time) were able to cast votes for the frst time on November 2, 1920. But many states passed laws making it more diffcult for Black men and women and other people of color to exercise this right. Those laws remained on the books until passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Suffragists protest in Lafayette Square, across the street from the White House, in January 1917.

The right to vote strengthens our democracy, promotes diversity, and furthers the interests of all Americans, if everyone casts a ballot. Today, public schools need federal funding to operate safely in the COVID-19 era. And our best chance to get it is at the ballot box.

Come November, there’s hope that the collective voices of women—who make up more than 80 percent of NEA member- ship—will exercise this right and bring about needed change.

Crowdfunding Is a Way of Life for Educators

Paying for school supplies or classroom projects can be too expensive for teachers to cover out-of-pocket. Which is why more educators over the past decade have turned to crowdfunding, namely DonorsChoose, which connects potential donors to classrooms in need.

From 2009 – 2018, educators submitted 1.8 million requests to DonorsChoose. A recent analysis by Grantmakers for Education revealed that while the majority of overall dollars go to high-poverty schools, requests from low-poverty schools are more likely to get approved.

The types of requests from low-poverty and high-poverty schools look very different. Educators in low-poverty schools are more likely to request resources related to econom- ics and foreign language classes.

On the other hand, as the needs of the whole child have gained more attention in recent years, educators in high-poverty schools have been shifting their focus to nonacademic resources. Subcategories such as “warmth, care, and hunger” (tracked since 2016) and “health and wellness” have seen huge increases.