Last winter, as Covid deaths peaked across the U.S. and images of haunted, worn-out healthcare workers filled our phones and screens, Alaska art teacher Jacob Bera wondered: “What can I do to help?”

“These are people in our communities who are always there for us. They’re working hard, not tooting their own horns,” Bera recalls. “We appreciate them. We need them. And I wanted to shine a spotlight on them.”

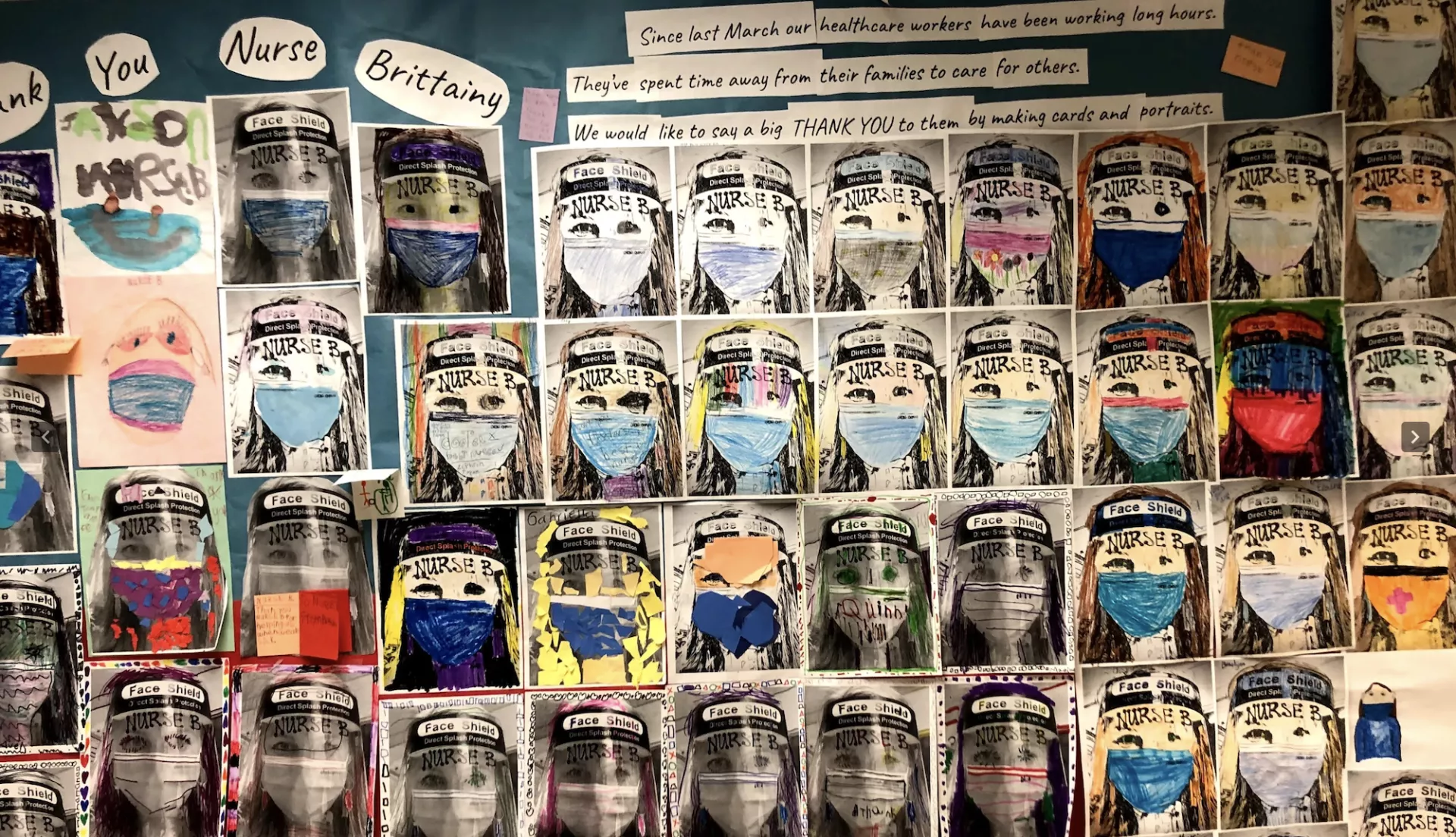

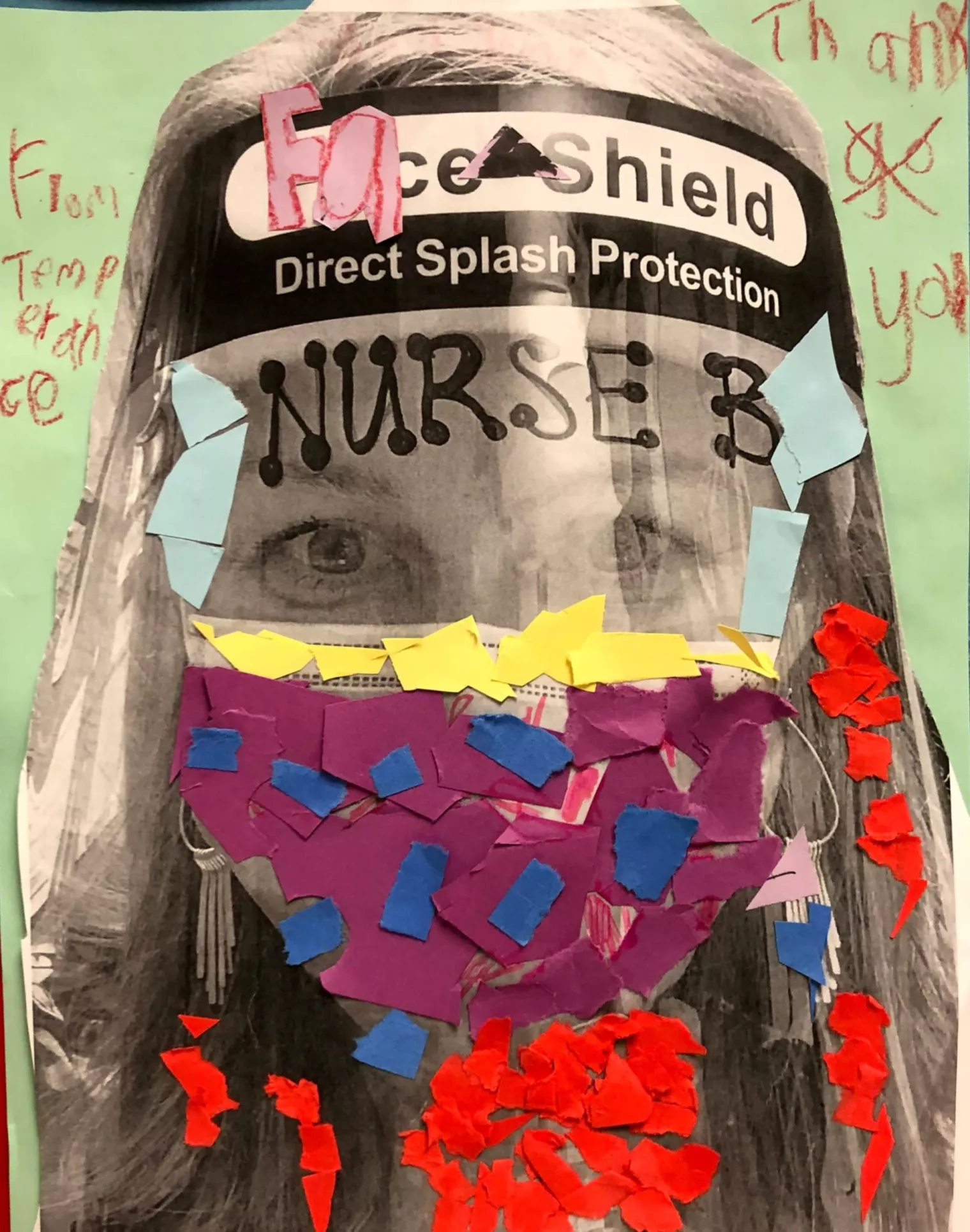

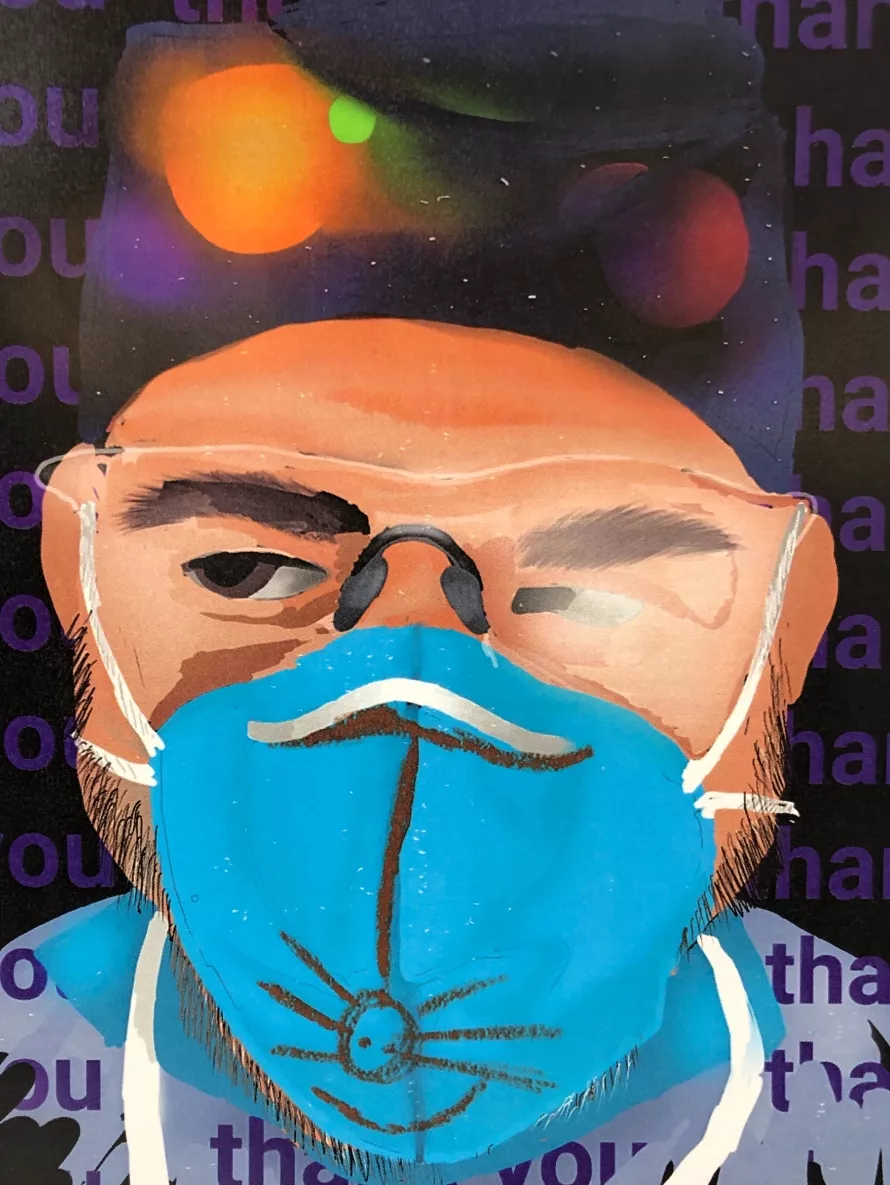

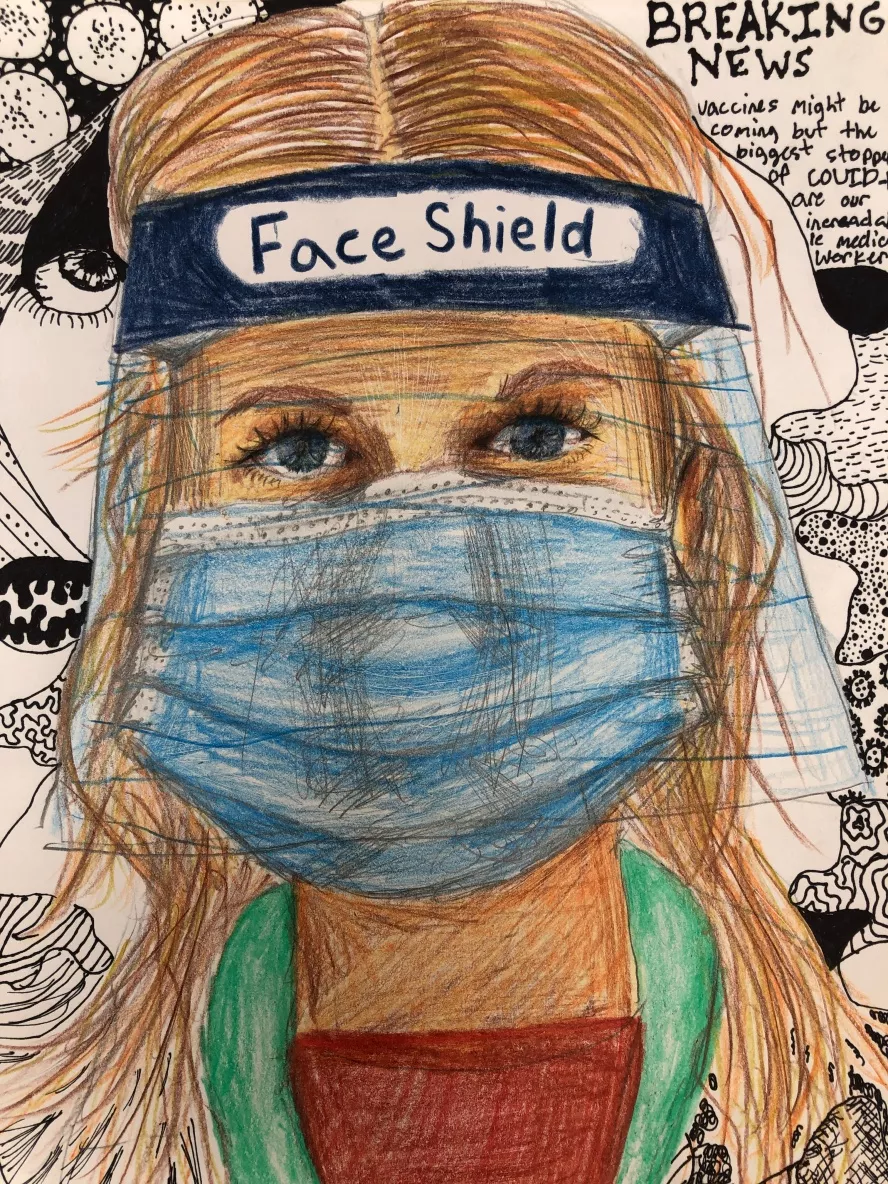

Inspired by the work of New York artist Steve Derrick, who paints portraits of healthcare workers, Bera invited local, Anchorage healthcare workers to share their selfies and a little information about themselves via an online form. He received so many submissions—more than 100—that he invited other teachers to join the project, which eventually became known as “Portraits of Those Who Serve.”

Sending thanks into the world

At Anchorage secondary schools, like Bera’s Eagle River High School, educators paired students with selfies. Some teachers folded the work into their art curriculum; others made it an optional, extra-curricular activity. Meanwhile, at Anchorage elementary schools, students made non-specific, thank-you art.

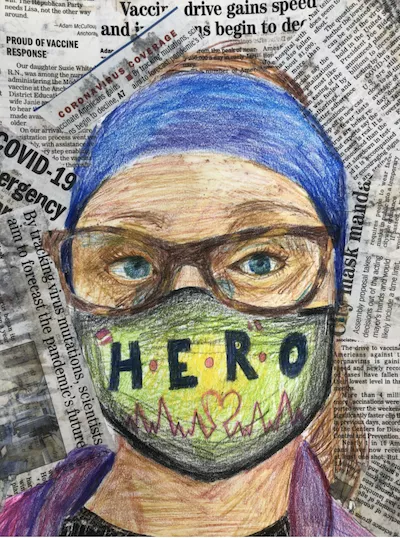

Emergency-room and ICU nurses, respiratory therapists, clinical lab workers, doctors, and even a hospital housekeeper who wondered if she qualified for the project (“Heck, yeah!” Bera said) had sent in their photos. Across Anchorage last winter, students studied those faces and read the accompanying notes.

“This is my wife Genoveva. She is literally my hero,” wrote a phlebotomist’s spouse. “Even when she is scared, or has fear entering a covid room, she faces that fear and does what she needs to do to try do her part in saving lives.”

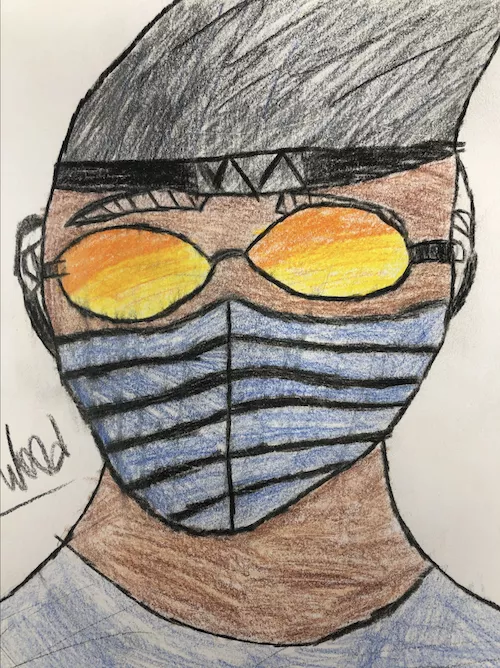

With sensitivity, respect, and colored pencils, Anchorage students rendered their portraits. “There was so much empathy,” says Bera. “The students really wanted them to know they cared.”

The housekeeper’s portrait is one of Bera’s favorites. When its young digital artist gave it to him for delivery to the hospital, he said to her: “It’s cool you did this portrait.” She told him, “A couple of years ago, my mom died of cancer. Every day in the hospital, after the nurses and doctors left, the housekeeper would come and sit with us and talk. She was so busy, but she would take that time. I know this isn’t that housekeeper, but this my way to send thanks into the world.”

What do you have to say?

Through assignments like these, Bera’s students build and improve artistic technique, of course. More critically, they learn to reflect on the world around them—and figure out what they have to say about it.

Most years, Bera also has his students participate in the Memory Project, which asks them to draw portraits of children living in international orphanages, refugee camps, and other war-affected communities—or to create inspirational art for those children.

“Everybody’s views are different and I’m not trying to push one message,” says Bera, who was honored last year by the NEA Foundation. “But I want [students] to be engaged and consider what they have to say and how they feel.”

He wants them to “crack the door open,” he says.