Homework - is it an unnecessary evil or a sound and valuable pedagogical practice? The media coverage of the debate often zeroes in on these two seemingly polar opposite views, even though they may not be all that far apart. Homework can be good until - well, until it isn't. Assign too much or the wrong kind (or both) and the law of diminishing returns kicks in, says Dr. Harris Cooper, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University, resulting in undue stress for students, aggravation for parents and no academic pay-off.

But as Cooper, author of "The Battle Over Homework: Common Ground for Administrators, Teachers, and Parents," recently told NEA Today, homework levels and parental attitudes haven't really changed dramatically over the years. Cooper also concludes - perhaps a shock of those who are convinced that very little in our classrooms is working as it should - "the vast majority of educators have got it right."

There's a lot of focus on homework now, but has it been scrutinized so heavily in the past?

Harris Cooper: Throughout the 20th century, the public battle over homework was quite cyclical. You can go back to World War I or a little after, when it was considered important for kids to exercise their brain like a muscle and that homework was a way to do that. During the 1930s, opinions changed. In the 1950s, people were worried about falling behind the communists, so more homework was needed as a way to speed up our education and technology. During the 1960s, homework fell out of favor because many though it inflicted too much stress on kids. In the 1970s and 1980s, we needed more homework to keep up with the Japanese economically. More recently, as everything about education and teachers is being scrutinized, homework has come into question again.

What's interesting is that the actual percentage of people who support or oppose homework has changed very little over the years. And the actual amount of homework kids are doing has changed very little over the last 65 years.

But haven't we seen an uptick in the amount of homework assigned to elementary students?

HC: There is a little bit of an uptick in lower grades. But when you look at the actual numbers, we're talking about the difference between an average of 20 minutes and 30 minutes. So you’ll find some people who say the amount of homework being given to 2nd graders, for example, has increased 50 percent. But If you look at the actual numbers, it's ten more minutes per night.

And probably a driving force behind that is obviously end-of-grade testing and accountability issues. Perhaps more legitimately is the importance of early reading. As they say, in third grade you learn to read, and in fourth grade you read to learn. So this has led to more reading assignments.

While most high school students are still doing approximately the same amount of homework on average, there's a great deal of variation. That's due to choices some kids make about how rigorous an academic program to take and the increased competition over college admissions. So there are a lot of kids out there taking four or five advanced placement and honors classes now, which might not have been the case a while back.

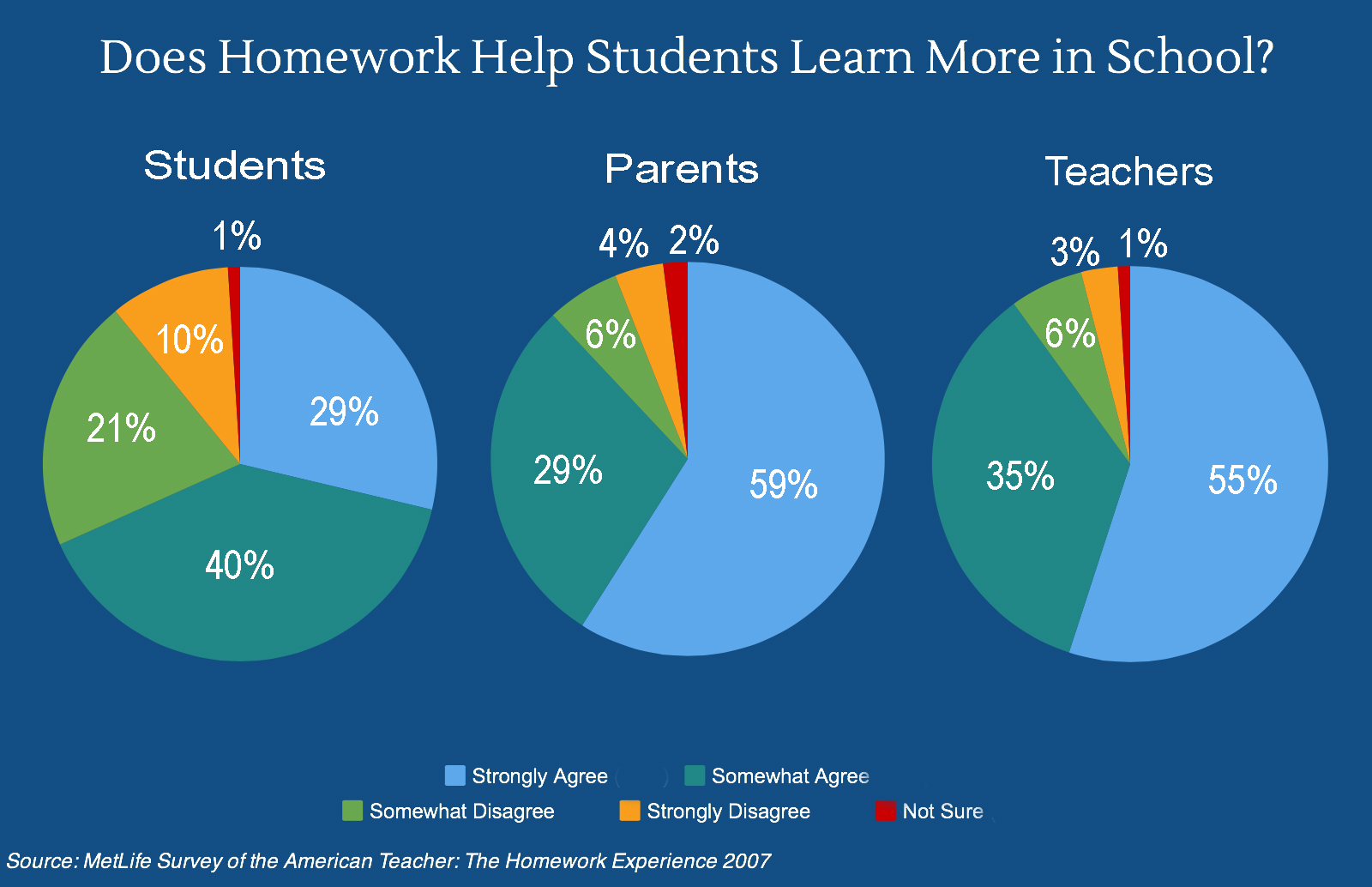

According to the MetLife Foundation national homework survey, 3 out of 5 parents said their kids are getting just the right amount of homework. One said too much and one said too little. That survey is a few years old now but I doubt that's changed.

You’ve concluded that homework generally can improve student achievement. At what grade levels do we usually see this effect?

HC: There's very little correlation between homework and achievement in the early grades. As kids get older, the correlation gets stronger. But there are experimental studies even at the earliest grades that look at skills such as spelling, math facts, etc. where kids are randomly assigned to do homework and not do homework. They show that kids who did the homework performed better.

But we're really talking about correlation here, so we have to be a little careful. It's also worth noting that these correlations with older students are likely caused, not only by homework helping achievement, but also by kids who have higher achievement levels doing more homework.

But at a particular point more homework is not a good thing. You've heard of the "10-Minute Rule," where you multiply a child’s grade by 10 to determine how many minutes you assign per night. This rule fits the data. So 20-minutes for a second grader is where you'd start. In middle schools, it's between 60-90 mins for 6th through 9th graders, about two hours later in high school. When you assign more than these levels, the law of diminishing returns or even negative effects - stress especially - begin to appear.

Have school districts coalesced around the 10-minute rule?

HC: From my experience, I have never seen a school district that recommends anything that isn’t consistent with the 10-minute rule. They won't use the term "10-minute rule" usually, but they’ll say, primary school grades will be assigned up to 30 mins., grades 4-6 up to an hour, things like that. But If you translate the policy to the 10-minute rule, it’ll be very similar. Nobody has a policy that says you can expect your second-graders to bring home two hours of homework. The only place you'll see a warning about it is in high school: you can expect half an hour a night per academic subject. Again, if the kid is taking AP, expect more.

What don't we know about homework? Where are the gaps in the research?

HC: We need to know more about the the differing impacts by subject matter. Regarding the 10-minute rule, one question I am frequently asked is, “Does that include reading?" Generally, the answer would be yes, but if we’re interested in kids' stress level, for example, they are more likely to burn out quicker doing math worksheets and studying vocabulary than if they were doing high-interest reading. So we really need more work on subject matter, on homework quality, on the level of inquisitiveness that it engenders and the way it motivates. Also we need to know more about the use of the Internet, especially as it relates to potential disparities between rich and poor and the ability to research at home.

Parental involvement is a huge homework-related issue. How can educators work with parents to keep their role constructive?

HC: Parental involvement is more important in the earlier grades and teachers should try to make sure that parents have the skills to teach the material so to avoid any instructional confusion. Educators should also remind parents to not place great pressure on their child and to model behaviors, especially with young children. For example, when the child is doing math homework, a parent could balance the checkbook to demonstrate how the skill can be used in adult life, or they can they read their own book while their child is reading.

Homework also keeps parents aware of what their child is learning. I've had some very emotional parents come to me about having been told by teachers that their child is struggling, that there might be a learning disability. The parents don't necessarily see it until they see their child work on homework.

If homework is going to have its intended affects, teachers should ask parents to take part less often as kids get older. If support from parents is withdrawn slowly, it can promote autonomous learning - teaching kids that they can learn on their own and they can learn anywhere.

Do you think overall the current debate or controversy over homework has been helpful and what, if anything, should educators take from it?

HC: Well, I recognize that the debate will always be there, but I generally choose to ignore it, or at least the people who, as the old saying goes, use science the same way a drunkard uses a lamp post - more for support than for illumination.

Homework is probably the most complicated pedagogical strategy teachers use because it's open to variations due to child individual differences and the home context. But the vast majority of educators have got it right. They're not going to satisfy everyone, because kids take homework home to different environments and to parents with different expectations. But, like I said before, three in five parents are satisfied and there's one in each direction - too much homework or too little. That probably means teachers are doing their job properly.

Photo: Associated Press