Key Takeaways

- Pre- and post-natal care increases the odds for healthy mothers and infants—and also boosts their ability to succeed in school.

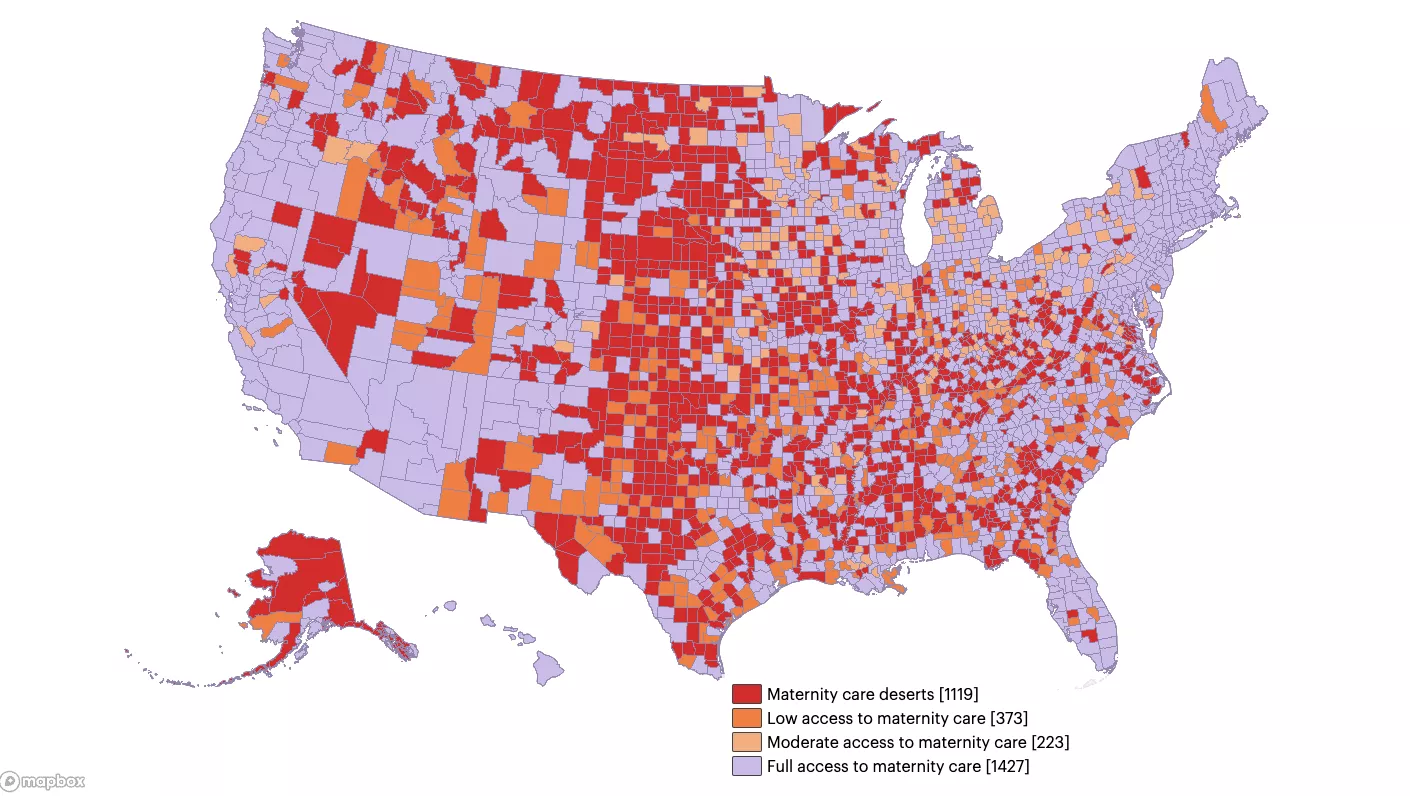

- Growing “maternity deserts,” which point to a shortage of OB-GYNs, especially in rural areas, are making it harder for women to access that necessary care.

- Solutions, including more equitable access to affordable healthcare and family leave, are possible where educators raise their voices together to advocate.

6.9 million

144%

The roots of student success are planted long before fresh-faced kindergartners, or even preschoolers, step into their classrooms. To find those roots, go back years earlier, before those children are even born.

Prenatal care for pregnant women—that is care provided by obstetrician-gynecologists (OB-GYNs) and maternal fetal specialists—is key to ensuring healthy outcomes for mothers and children. According to the World Health Organization, infants whose mothers get this kind of medical care are five times less likely to die in infancy and three times less likely to have low birth weights, which are significantly associated with lifelong neurological problems and low academic achievement.

The problem today is that a growing shortage of OB-GYNs is making it more difficult for women to get the medical care that leads to healthy babies and healthy outcomes. The situation is so alarming that NEA members brought it to the attention of the Representative Assembly last year.

“There is a shortage of providers, just like there is a shortage of educators,” said retired teacher Lynn Garcia, of Buffalo, New York, “and when we have a shortage, people don’t get the healthcare they need… A child’s entire life is impacted, including how well they do in school, if they graduate, and their future in the workforce.”

The Lives at Stake

Obstetricians deliver babies, as well as provide pre- and postnatal care, including ultrasounds, pre-eclampsia tests, etc. Gynecologists screen for cancers, diagnose and treat conditions ranging from infertility to incontinence, and more. As about 75 percent of U.S. teachers are women, the vast majority of NEA members rely on OB-GYNs to keep them healthy and alive.

Unfortunately, depending on where you live, it might be a challenge to see one of these doctors. Between 2011 and 2021, 25 percent of rural hospitals with OB units shut their doors to pregnant women. Many of those hospitals cited costs or staffing shortages, which are likely to get worse. In 2023, the number of medical students applying to ob-gyn residency programs declined by 5.2 percent overall, according to the American Medical Association. In places with new abortion bans, the decline is even steeper: in Texas, they dropped by 19 percent; in Alabama and Tennessee, they dropped by 21 percent.

Today, more than a third of U.S. counties, mostly in rural areas, particularly in the South and Midwest, don’t have a single obstetrician or birthing center. In 2022, the latest March of Dimes report on maternity deserts showed that 6.9 million U.S. women live in places where they struggle to get pre-natal or post-natal care.

This is a life-or-death issue: the women who live in maternity deserts are three to four times more likely to die in pregnancy or delivery, according to March of Dimes. And it’s getting worse.

From 1999 to 2019, the U.S.’s national maternal mortality rate more than doubled, going from 9.65 to 32.2 deaths per 100,000, according to the Journal of American Medicine. Even more shocking? The rate for Black women is 67.6 deaths per 100,000, three times higher than the rate for white women. In five states—Louisiana, New Jersey, Georgia, Arkansas and Texas—the maternal death rate for Black women increased by 93 percent over the decade.

Common reasons for death after birth include mental-health conditions, excessive bleeding, and cardiac and coronary conditions, such as blood clots. These are all things that medical attention could alleviate.

It’s also an equity issue, says Garcia, as “we are expecting lower-income individuals, particularly in rural areas, to travel great distances to access quality health care.”

Echoing this concern, retired educator Lynne Kelly, of Allentown, Penn., says that “people living in maternity deserts or areas with shortages of physicians are more likely to be living in poverty and have more healthcare concerns with low access to telehealth as well.” They’re also more likely to be Black or Native American: the March of Dimes study shows that 1 in 4 Native American babies and 1 in 6 Black babies are born in areas with little to no maternity services.

Quote byLynn Garcia , Retired teacher, Buffalo, N.Y.

Solutions are possible

Multiple studies show how a lack of prenatal care leads to lower birthweight children with more neurological problems. One such study, published in 2015, found that lower birthweight children were 2 to 6 times more likely to have poorer grades, and also to have emotional or behavioral problems.

More recently, a University of Pennsylvania researcher looked specifically at the relationship between prenatal care and school outcomes — and found that children who received prenatal care were more likely to persist in school.

“If the child doesn’t have a good beginning, they are behind their entire lives, which impacts their education, future in the workforce, and adult livelihood,” says Kelly.

But solutions are possible—especially when NEA members raise their voices and demand them from lawmakers. Here are a few:

- Expand Medicaid’s post-partum care. Currently, Medicaid covers 42 percent of births in the U.S., but coverage for post-partum care has varied among states. As of now, 47 states have extended care to 12 months; two states (Idaho and Iowa) are planning to expand it to 12 months; one, Wisconsin, has extending it to 90 days.

- Expand Medicaid’s coverage for doulas. Doulas, who provide support to women during labor and delivery, are not currently covered by Medicaid, but advocates believe they improve health outcomes for women and children. They may be particularly helpful in maternity deserts.

- Improve family leave policies. Union members have had much success in recent years, either at the bargaining table or in statehouses, to improve family leave policies. For example, in South Carolina, educators recently won a state law that provides six weeks of paid family leave to new parents. In states like Minnesota and Delaware, they get 12 paid weeks. Meanwhile, new collectively bargained contracts in places like Quincy and Malden, Mass., also provide 12 weeks.

- Bargain and/or advocate for reproductive services. “Pregnant people should be able to obtain wellness checks and prenatal care without the stress of having to worry about how to access a provider or whether these services are covered by information,” stresses Kelly. For information on how educators can advocate for broad comprehensive reproductive healthcare coverage, check out the NEA report, “NEA Bargaining & Advocacy in a Post-Roe Environment.” It includes guidance around bargaining such topics as insurance coverage, in-network vs. out-of-network care, types of health plan coverage, waiting periods for benefit coverage, out-of-pocket expenses, mental health, telehealth, travel expense reimbursement, and privacy-health information.

Educators also are heartened by the Biden-Harris administration’s attention to this issue. In September 2023, the administration announced $103 million in investments toward improving maternal health, including $8 million to train more nurse-midwives and $4.5 million to train a home-visiting workforce.

“Our nation is facing a maternal mortality crisis,” said Vice President Kamala Harris. “Today’s announcement of additional strategic investments to address the maternal health crisis demonstrates our unwavering commitment to the health and well-being of all women and their families.”

NEA Senior Policy Analyst Cynthia Blankenship contributed to this article.