Key Takeaways

- Educators across the nation have been affected by gun violence in their schools and their communities.

- Now, union educators are intensifying their efforts to help identify root causes of violence in order to save lives and reduce community trauma.

When Ovidia Molina, president of the Texas State Teachers Association, first heard that 19 students and two educators were killed by a shooter on May 24, 2022, at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, “it just did not compute, I couldn’t take it in,” she recalled.

The overwhelming grief and lasting trauma persist not only with the victims’ families, said Molina. The massacre shattered the entire community.

Sadly, she is just one of many educators across the nation affected by gun violence. Teachers and support staff in every job category—from cafeteria workers to college faculty and counselors to school bus drivers—have survived shootings. They have lost colleagues and students and family members. They have nurtured survivors through long recoveries from gunshot wounds.

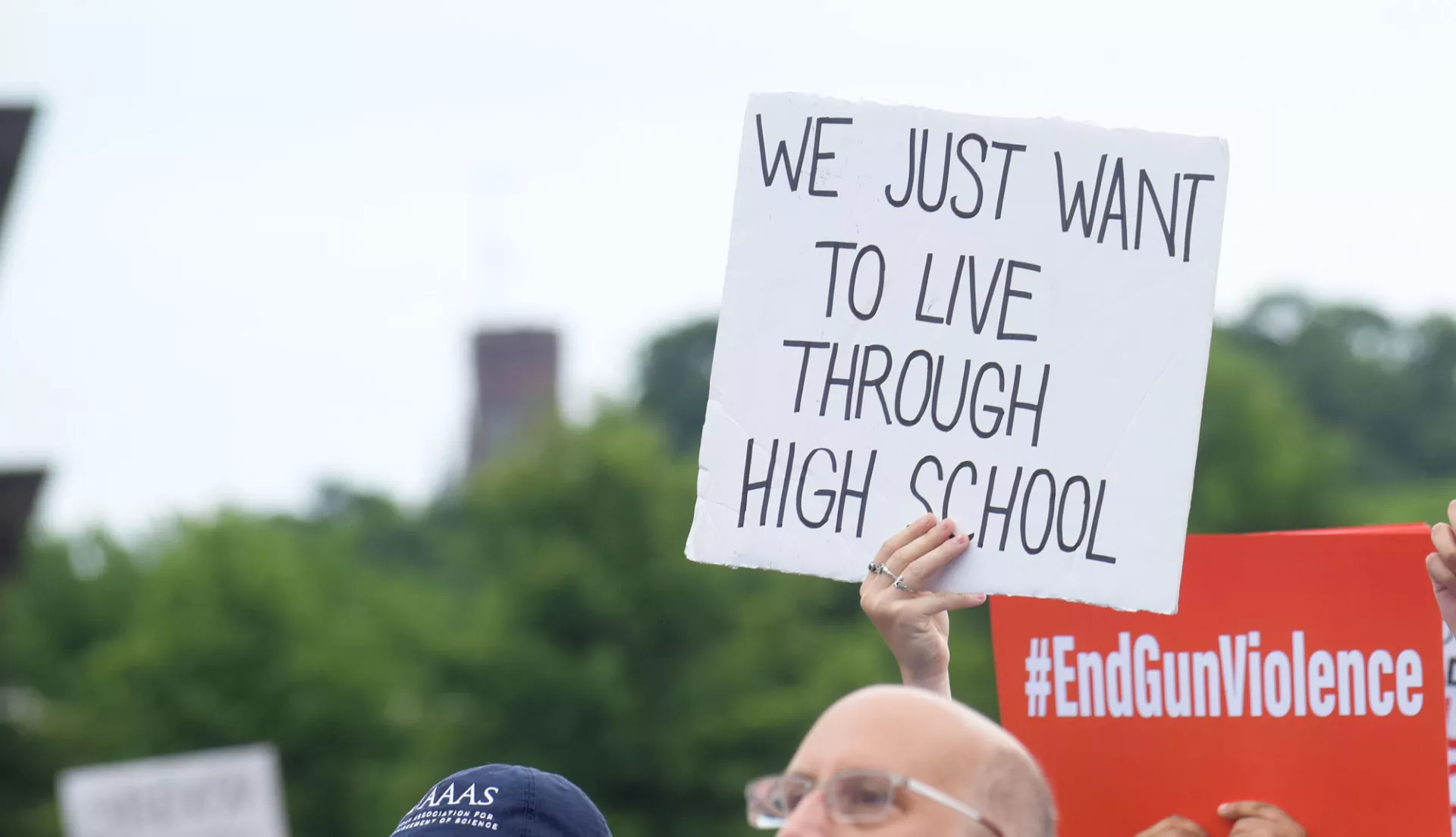

Now, educators are intensifying their efforts to help end the epidemic of gun violence in America.

Molina was one of dozens of educators and union staff from around the country who met at National Education Association headquarters in Washington, D.C., last week to determine the next steps that the NEA and its affiliates will take to make schools and neighborhoods safer.

Throughout the day, educators examined possible solutions to the complex roots and results of gun violence, drawing on participants' diverse backgrounds, knowledge, and experience.

They started with some critical questions: When it comes to the prevention of gun violence, what is the role of policymakers? Parents and educators? School boards or trustees? Teacher preparation programs? Police departments? Gun rights advocates? Health insurance companies? They examined how students are influenced by the messages from these adults, as well as what they see and read on social media.

They examined their own roles as leaders on their campuses and as trusted community members.

The goal was not to categorize entities as “us against them.” It was to pinpoint opportunities to work together to save lives and reduce community trauma.

That Was Then, This is Now

In 1999, Zachary Taylor Martin was a freshman at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo., when two fellow students shot and killed 12 students and a teacher and injured another 21 students before turning the guns on themselves. Today, Martin is a teacher there.

He says it was the outpouring of community support that inspired him to want to give back, to become a teacher and stay at Columbine High School. As an educator, a parent to two young children, and a shooting survivor, Martin is deeply invested in advocating for gun violence prevention.

“Back then it was almost like we couldn’t have known this would happen,” Martin explained. “But if I were a 15-year-old experiencing this today, I would feel differently. Because now we know there are things we can do, positive steps we can take to try to avoid this ever happening again.”

This summer, educators applauded the passage of the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, federal legislation that represents the first substantive change to gun safety laws in over 20 years. The act also bolsters the mental health system, including school safety programs.

One of the law’s major accomplishments is a historic expansion of the Medicaid in Schools program, which will help states provide more mental health services for students. NEA will help educate state decision-makers to ensure that school-based providers are included in state plans.

But it is only a first step in the change that educators, students, and parents know is needed.

The bill “will absolutely help save lives, but we cannot stop here,” NEA President Becky Pringle said at the time. “Lawmakers from both parties need to do more to pass comprehensive measures to stop the massacres at our public schools and communities.”

In July, NEA members at the annual Representative Assembly voted to issue a national call to action "to ensure that all students, educators, schools, campuses, and communities are safe from gun violence." The summit is part of that effort.

Molina, Martin, and several other educators and union staff shared their stories during an emotional but hopeful panel discussion. Common frustrations surfaced. Too often after a shooting, a narrative of blame leads to further trauma for the school community. And all of the participants said too little had changed in terms of policies that could prevent future incidents.

“In Texas, there is no talk about changing gun laws. All we got from our governor were panic buttons in our classrooms and empty promises to expand mental health services,” said Molina. “Our students shouldn’t have to train to survive being shot. Teachers shouldn’t have to pledge to stand in front of a bullet so students feel safe in the classroom. Parents shouldn’t have to feel scared to send their kids to school.”

“Help us stop the attacks, that’s what I want,” Molina said.

Educators want solutions that work—not the “hardening” of schools or campuses, which includes more metal detectors, excessive surveillance cameras, and worst of all, the push to arm educators.

Deborah Gatrell, another panelist at the NEA summit, is both a teacher and a Lt. Colonel in the Utah Army National Guard. While Gatrell is highly trained in the use of firearms, she says she would never want a weapon in the classroom.

“I’m a teacher and you are my students and I can’t see you as a potential threat and then teach you,” Gatrell said.

She has been outspoken in her opposition to arming teachers, a tremendously dangerous idea that has been proposed in a number of state and local legislative bodies in recent years.

“It’s frustrating, but I’m not one to give up,” said Gatrell, who returned to the idea that educators and their unions must keep talking to their communities and to decision-makers.

“There are some people who are very fixed in their world view, but most people are somewhere in the middle. If we can approach them in a way that invites them to share, we can at least discuss why things like arming teachers is a bad idea.”

Next Steps

Eva Mays, a clinical social worker in the Los Angeles Unified School District, has seen what violence does to families. Before joining the school system, she worked with underserved adolescents in the juvenile justice and foster care systems and counseled families in the public health system.

“We’ve entered into a time when schools cannot just focus on academics,” said Mays. “We relentlessly screen kids to determine their math and reading levels; we also need to do screenings to find out if they’ve had a loss, if they have one stable adult at home, if they have lost housing,” she said.

“There are so many conversations that accompany how to address gun violence.”

Other strategy discussions during the summit ranged from the importance of electing leaders who understand the need for better gun laws to protections for students and employees that can be gained through bargaining and labor management collaboration.

NEA President Pringle praised the conference participants’ dedication, saying, “I appreciate your openness to bring your whole heart to this work. It is hard, but it is necessary.”

“As long as we are living with gun violence in this country, we the NEA will do everything we possibly can to lead change.”