Are smart students from poor families more likely to be overlooked for gifted or high-level math classes? The answer is a resounding yes, a team of North Carolina investigative journalists has found.

Are smart students from poor families more likely to be overlooked for gifted or high-level math classes? The answer is a resounding yes, a team of North Carolina investigative journalists has found.

Last month, led by reporter Joseph Neff, the News & Observer in Raleigh, N.C., unveiled a three-part series, called “Counted Out,” that showed convincingly how high-achieving, low-income North Carolina students are very often excluded from the classes that would challenge their abilities and help them attend college and climb out of poverty, while equally achieving, wealthier students are counted in.

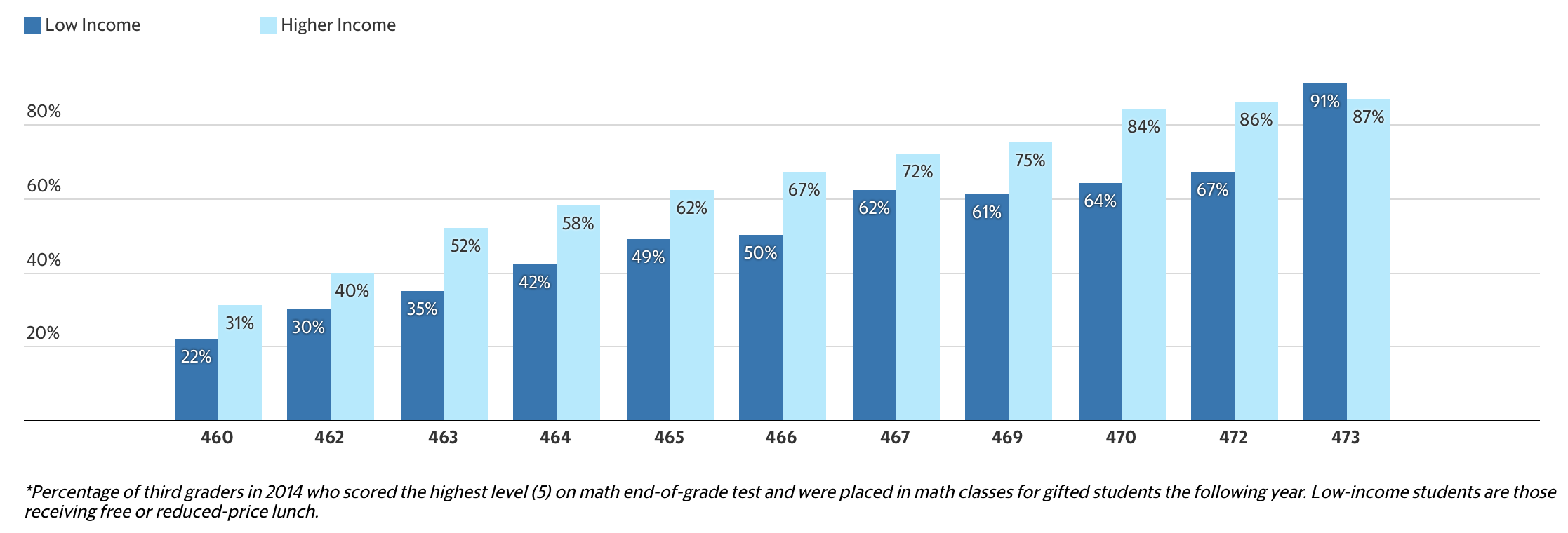

Using anonymized state records involving tens of thousands of students and zeroing in on end-of-grade achievement tests, Neff found that just one out of three low-income students with superior math scores was labeled gifted by educators, compared to one out of two students—with equal achievement—from wealthier homes. These high-potential, low-income students also were found much less likely to take high school math in middle school, “an important step toward the type of transcript that will open college doors,” notes Neff, with his colleagues Ann Doss Helms and David Raynor.

Neff and his colleagues identified a “web of barriers” that work against low-income students, including some districts' complicated measures of giftedness that favor students from English-speaking homes with high exposure to sophisticated language. They also found low-income parents who were less likely to ask the right questions, or know how to advocate for their children. Bottom line: “The unequal treatment during the six years ending in 2015 resulted in 9,000 low-income children in North Carolina being counted out of classes that could have opened a new academic world to them."

Recently, Neff spoke with NEA Today about their work.

Q: How did the series develop? Was it generated by reader feedback, or some other impetus?

A: One of our top editors asked us to do something about education, and so the first thing I did was to go to the Department of Education and request a list of databases. We found an ocean of data from every school district, every school, every classroom, every student…We don’t know who the students are, because it’s anonymized data, but we know quite a lot about them—their race, their family’s income, the classes they’ve taken.

There’s been a lot of reporting on the achievement gap, but most of it has focused on kids who are below grade level and what’s done to bring them up. We thought we’d look at kids above grade level, the highest achieving kids, and how they’re sorted and tracked, as early as fourth grade. What we found is that socioeconomic status is the most significant, predictive factor in the data.

Source: "Counted Out," The News and Observer, Raleigh, NC. (Click to Enlarge)

Source: "Counted Out," The News and Observer, Raleigh, NC. (Click to Enlarge)

Q: NEA formally turned its attention last year to eradicating institutional or structural racism. With that in mind, how much did race—whether a student is Black or Hispanic—affect students' placement?

A: There were definitely racial and ethnic disparities as well. Asian students are more likely to be placed into these rigorous classes, even those from low-income homes. Among middle-class families, there is a significant difference among races. Middle-class Black and Hispanic students are less likely to be placed. We plan to return to race at some point and look at this more closely.

Q: You talk with an African-American mother who goes to great lengths to keep her son—who is a great math student—in challenging math classes. Did she believe racial biases played a part in her son’s class placement?

A: She suggested race may have a role, but at the end of the day the biggest lesson for her was learning how to advocate. She didn’t know how to do it. She was a high school graduate who trusted the experts. Learning how to get in there and fight for her son was, to her, the biggest issue. She relied on the advice of her cousin, who was a teacher, who told her that the parent’s voice is always the last voice. And she learned from a local minister [who runs an after-school STEM program for students] about how to go into the classroom, how to make an appointment, prepare a list of questions, and so on.

Q: You identify several possible strategies that would help low-income students get access to the classes that would help them realize their potential. One would be to simply fill gifted classes with the highest achieving students. Another is to hire more teachers of color. A third is to hire more school counselors.

Basically these counselors are just processing kids. To think you could know any kid when you have a case load of 400… you’re just pushing paper. It seems like a lot to me!

Video: Counted Out

.mcclatchy-embed{position:relative;padding:40px 0 56.25%;height:0;overflow:hidden;max-width:100%}.mcclatchy-embed iframe{position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%}

Q: What kind of response have you gotten to the series?

A: It’s been very positive. The story just came out a few weeks ago, so we won’t see things like budgeting and legislating immediately. The governor has said he’ll make it a priority, all these talented kids who go missing. [He said he was appalled.] The Republican president of the state Senate has pointed out things he’d like to fix, including much more use of data in placing kids. He believes data would be much more colorblind and blind to socioeconomic factors. There’s a lot of people calling the paper to tell us stories about their students. There’s that kid in the series, Christian, who plays in a marching band and says he hopes to someday have his own trumpet. Five people have called us and offered him trumpets!

Q: Did the series meet the goals you had for it?

A: We saw this basically as a story of lost potential. In reporting, we didn’t find any animus or bad faith or ill will… we’re not saying this principal is bad, or this legislator, or this teacher. Our assumption is that everybody wants the best things for our kids. Our goal was to point out this issue with data so people would be forced to say yes, this is a problem and we will have to deal with it. In that, I think we were successful.