Key Takeaways

- After increasing salaries, rural Baker City started the school year without a single unfilled teaching position. This is extraordinary!

- The national teacher shortage is a huge problem for students. Pay is clearly part of the solution.

- Other places with significant teacher pay increases, such as New Mexico, also are seeing increased applicants.

Babies are amazing… and expensive. Earlier this year, Oregon teacher Lindsey Rogers was expecting her first child, and she and her husband Jared, also a teacher, were wondering how they ever would afford it.

The average cost of infant care in Oregon runs well over a $1,000 a month. “It’s so expensive, and it’s such a stressor,” says Lindsey Rogers, a third-grade teacher at Baker City’s Brooklyn Primary School.

Then they heard the news about the Baker School District’s new salary schedule. “The first thing we both thought of when we heard about the raise, was, ‘we can afford daycare!’ It was literally the first thing we said to each other,” she says.

Today, rural Baker City, located along the Oregon Trail, about 120 miles northwest of Boise, Idaho, is one of the highest-paying districts in the state. Since the raises were announced by the Baker Education Association, teachers have begun looking to buy their own homes, pay off their cars, and yes, even to start their own families.

Moreover, the district has become more attractive to prospective employees. Earlier this month, when students returned to Baker City’s nine public schools for the start of the 2023 – 2024 school year, every student had a qualified educator in their classroom. The district had not one unfilled vacancy nor one emergency-certified educator. Indeed, while districts across the nation continue to struggle with an educator shortage, Baker City seems to have solved the problem.

“Many of our administrators had never before had multiple, highly qualified candidates for a role. It’s a different conversation and it’s an exciting one!” says Baker Superintendent Erin Lair.

Pay Matters

Other places could learn from Baker. Last month, weeks after Florida students returned to school, the state still had about 7,000 unfilled teaching vacancies—about 900 more than this time last year—which means tens of thousands of Florida students will be attempting to learn from a rotating cast of non-certified subs.

While pay isn’t the only problem in Florida, the state ranks 48th in the nation, in terms of average teacher pay, according to NEA’s Rankings and Estimate annual report.

Similarly, in West Virginia, which ranks 50th for pay, the school year started with about 1,500 vacancies. “We have to make [the profession] more attractive, both financially and with respect,” says West Virginia Education Association President Dale Lee.

Pay matters. It’s not the only thing that matters—as the needs of students grow and become more complex, support for educators also is critical. Many feel overworked and overwhelmed—and underpaid. The fact is that teachers also make about $3,644 less than they did 10 years ago, adjusting for inflation.

The gap between teacher pay and what similarly educated workers make, known as the “teacher pay penalty,” has never been higher. A bachelor’s degree in education is the lowest paying type of bachelor’s degree—and the story is the same with master’s degrees. It’s not a coincidence that the number of college students pursuing a degree in education has never been lower.

“Who will choose to teach under these circumstances?” Pringle asked Education Week earlier this year. “Educators who dedicate their lives to students shouldn’t be struggling to support their own families.”

Turning the Tide

Across the nation, NEA members are fighting to turn the tide. Around state houses and bargaining tables, they are winning pay raises that retain and attract educators.

Last year, thanks to NEA-New Mexico members, the state legislature passed a bill that gave all school employees a 6 percent raise and boosted base pay for Level 1 teachers to at least $50,000 a year; for Level 2 teachers to at least $60,000; and for Level 3 teachers to at least $70,000.

In Bernalillo, New Mexico, the local union took it a step farther. On top of the governor’s raises, the union’s bargaining team won an additional nine days to the contract. “We’re starting Level 3 at $85,000,” says local president and lead negotiator Jennifer Trujillo. Their neighboring district is at $80K.

Trujillo’s goal is to attract “the most qualified, the most seasoned teachers,” she says, because these kinds of teachers are proven to be more beneficial for students. With National Board certification, Bernalillo’s Level 3s make $95,000. Add in a TESOL certification and they hit $98,000. “Our test scores have gone up. Our instruction has improved,” she says. Meanwhile, Trujillo has made it clear to district officials that more pay can’t mean more work on teacher’s plates.

When school started this year, Bernalillo might have had a few vacancies in special education, “but our core classes were covered—and I really feel it’s due to the increase,” she says.

Meanwhile, in Alabama, where the legislature passed historic pay raises for teachers in 2022, Alabama Education Association Executive Director Amy Marlowe points to a decrease in teacher retirement rates—and the return of many retirees to the profession. “We didn’t expect people who had been retired some maybe 10, 15 years saying, ‘You know what, I’ve got a chance here to permanently raise my retirement for the rest of my life, so I’m going to go back in and take advantage of it,’” she said.

"I Can Afford..."

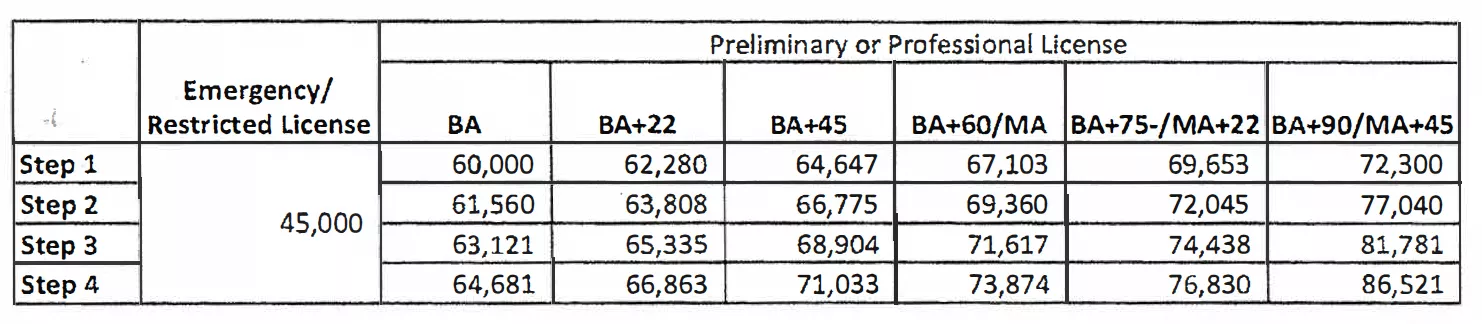

In Baker City, the new raises have changed the game for teachers. Starting this past July, the salary floor for teachers went from $38,000 to $60,000. Previously, a Baker teacher would have to work at least 13 years and have graduate-level coursework to get to $61,000. The top of the scale also increased to nearly $90,000.

“I might be able to actually buy a house and plant roots here,” says middle-school math teacher Alli Ferdig. Her car? She’s going to pay it off. Her student debt? She’s working on that, too. “I’m thinking about going back to school to get some different certifications—I never could have afforded that before,” Ferdig says.

This is exactly what Lair and union president Toni Myers want for Baker’s teachers and students: educators who can stay and thrive in their small community. The most significant factor in a student’s ability to achieve is whether they have a qualified, experienced teacher in front of them, says Lair.

To make that happen, teachers need to get paid, says Lair. “We talk about teaching as a calling, but I still need my calling to pay my electrical bill,” says Lair. “I feel like the way to fix the teacher pipeline problem is to make it a viable career choice.”

So, last year, Lair called Myers with an idea. Their 16-step salary schedule would be transformed into four, starting at $60,000 and topping out at $86,521. The focus would be on bringing up the bottom and getting people to a “professional salary” faster. It will cost more this year—an additional $2.3 million—but Baker has a healthy reserve, Lair notes.

“When I brought this to membership, we were on Zoom and I asked everybody to turn on their cameras because I wanted to see their faces. I wanted to see the impact,” Myers recalls. It was huge. Teachers cried. They said things like, “I can afford to turn my heat up past 65,” and “I can afford to have a baby.”

For Lindsey and Jared Rogers, it means their infant daughter started last week at a safe, high-quality childcare center, which is a huge relief to her parents. “I really hope other districts are able to do what Baker did,” she says. “I believe teachers deserve it and it’s only going to help education in the long run.”