Nancy Cogland really didn’t think it would happen again. But in early 2019, there she stood facing the possibility that her job—and those of the other 166 paraprofessionals in Old Bridge Township, New Jersey—could be outsourced to a private company.

The last time they faced this threat, the district's paraeprofessionals were, "caught a little off-guard," Cogland says. That was eight years earlier, when the school board of this 10,000-student district—saddled with new cuts in state aid and a large budget gap—announced they were considering privatizing paraprofessionals. With a quick vote scheduled, the board left it up the paraprofessionals — lose your jobs or give up your family and medical benefits.

“We had no real choice and no warning,” Cogland recalls. "We obviously didn't want to lose our jobs to a private company, so we agreed to surrender our benefits."

Luckily, those benefits were reinstituted in the next round of bargaining. But after announcing another round of state cuts in 2018, the school board looked again for savings. Again, the paraprofessionals’ jobs were on the chopping block.

Many districts already outsource other education support professionals (ESP), such as bus drivers, school custodians, and cafeteria workers. The focus on paraprofessionals, says Tim Barchak, senior policy analyst with the National Education Association, opens up a relatively new front in the privatization fight.

"Everyone is vulnerable now," he says. "The key is to change the environment in districts to make it more difficult for privatizers to thrive."

Penny Wise and Pound Foolish

Mapping the march of school privatization across the United States reveals significant expansion of charter schools and, to a lesser extent, private school voucher programs. Zoom in closer, and you’ll see a concentration of privatization inside public schools: the outsourcing of school staff. That is, after all, what privatization is—turning a public good over to a private entity.

Everyone is vulnerable now. The key is to change the environment in districts to make it more difficult for privatizers to thrive." - Timothy Barchak, National Education Association

Many school districts insist such a move is necessary because they can't afford pension obligations and health care costs. Or it could also be "plain old opposition of taxpayers to paying more than they would like," says Samuel Abrams, director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Educationat Columbia University in New York City.

ESPs are frequently the easiest targets. "Often the specific service they provide is not viewed as core to the mission of educating our students," Barchak explains. "And these workers are not usually allied with stakeholders in the community," making it a challenge to build alliances when these threats materialize.

Although not ESPs, substitute teachers are viewed the same way and are also contracted out to private firms. Substitutes usually don't need to be licensed educators, and are more deeply embedded in the gig economy than any other school job category.

Whoever the specific target, says Abrams, "ultimately, such privatization is penny wise and pound foolish. Privatizing these jobs will mean hiring people with less experience and generating more turnover. This is the opposite of what schools need."

School board members say they needed to look for savings, but "it was our job to explain to them what our value is to the students we serve," said paraeducator Nancy Cogland.

School board members say they needed to look for savings, but "it was our job to explain to them what our value is to the students we serve," said paraeducator Nancy Cogland.

On the Chopping Block

Many flush with venture capital funds, companies are deploying aggressive marketing campaigns, ready to swoop in and privatize school services in any district looking to cut costs. Kelly Staffing Services, Swing Education, SPUR, and EduStaff offer enticing—although short-sighted and often misleading— offers of savings, quality, and streamlined efficiency. As for the individual workers, some companies hope to usher them into the flexible world of the "gig economy."

The pitch: Agree to self-privatize and get a hefty one-time boost in salary. Left out of the pitch: Say goodbye to adequate health insurance and pension security.

Flipping a School Board Can Make All the Difference

Flipping a School Board Can Make All the Difference

Transferring the work of public school employees to the private sector leads to inferior services and fewer connections to students and their education. A successful campaign by a Pennsylvania local association struck a blow against privatization that is having a lasting impact.

Substitute teachers are a lucrative market. With growing teacher shortages, schools need quality substitute teachers more than ever. But in many states, subs work without any employee protections or access to health and retirement benefits.

Some substitute teachers, like Greg Burrill, like the flexibility but he belongs to a union and works in Oregon—a state that requires certification. He knows he’s lucky. "Substitutes need protection, especially as more districts farm the service out to private companies," Burrill says.

Kelly Educational Services has a foothold in many districts, including Shawnee Mission, Kansas, where Laura Holland teaches. She has often complained about the quality of the substitutes being sent to her school. "Generally, they don't belong in the classroom,” Holland says. “They're not licensed or prepared. These companies view them as temp workers. That's a disservice to students.”

'We Weren't Going to Stand For It'

Fortunately, the paraprofessionals in Old Bridge Township had critical structure and relationships in place, and persuaded the school board to drop its outsourcing plan. They made sure the district knew that any short-term savings were not worth the inevitable decline in quality and accountability.

"The fact is, you get what you pay for," Cogland says. "We weren't going to stand for it, and the parents weren’t going to stand for it."

After the 2011 cutbacks, Cogland had become more involved in her local union, Old Bridge Education Association, and participated in workshops and leadership trainings sponsored by the New Jersey Education Association. By the time the privatization threat re-emerged in 2019, Cogland and her colleagues were ready to organize and mobilize the community.

All the paraprofessionals in the district work with special education students. Their parents are organized and very vocal in protecting their students, and they immediately went to bat for the paraprofessionals. Strengthening those relationships was front and center in the campaign to ward off privatization.

The school board got the message, and in May 2019, took the proposal off the table.

“It's the board's job to find ways to save money,” Cogland says, “but it was our job to explain to them what our value is to the students we serve.”

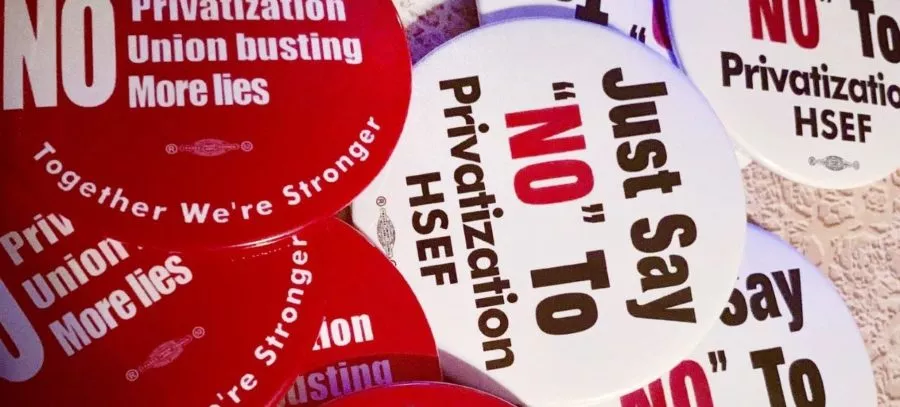

Hillsborough County school custodians rally against district proposal to outsource their jobs.

Hillsborough County school custodians rally against district proposal to outsource their jobs.

It's Hard to Privatize Names

The 1,500 school custodians in Hillsborough County, Florida—the eighth-largest school district in the country—also tapped into a reservoir of goodwill in 2019, when they turned back an attempt to outsource their services to a private contractor.

"We were able to use the media and our public protests to talk about what our custodians do for our schools and students," said Iran Alicea, a school security officer and president of the Hillsborough School Employee Federation (HSEF). "You're talking about replacements entering our school buildings. These are workers who have no real connection to the school. Would they really always be there for the students?

Including when disaster strikes—literally.

Civics teacher Scott Hottenstein recalled the critical role his school's custodians played during Hurricane Irma in September 2017, when the school became an emergency shelter. The custodians worked around the clock to keep the shelter clean. “Our entire custodial staff moved their families to the school for 48 straight hours to serve the community. Are you going to get that with privatized janitorial services?” Hottenstein asked the Hillsborough school board in May 2019, as it debated privatizing their jobs.

In October, the board scrapped the proposal.

That is, until it’s back on the table—or the board tries to outsource another job category. As long as school boards are looking for savings, and private companies see public schools as profit centers, the threat of privatization looms.

"Unfortunately, that's the world we live in," Barchak says. "But kids don't just drop into a classroom ready to learn," he adds. "Every school has a network of caring adults who have to do their job professionally every day to make that happen. ESPs need to tell their stories about what they do and develop relationships with stakeholders. It's relatively easy to privatize the ‘bus drivers’ or the ‘custodians.’ It's a lot harder to privatize the individuals who have names that know and take care of your kids."

NEA resources on fighting ESP privatization in your community