Are Your Students Reading Enough Non-Fiction?

Every year, new fiction books hit the market with a rainbow of diverse and engaging characters for young readers. But there are just as many terrific new titles in nonfiction.

One isn’t better than the other, and educators should offer and teach both, says the National Council of Teachers of English.

To learn more about nonfiction trends and how to help students connect with these books, NEA Today spoke with Melissa Stewart, who has authored more than 200 nonfiction children’s books.

Is nonfiction making a resurgence, or has it always been popular with teachers and students?

Melissa Stewart: Nonfiction has always been popular. But teachers often don’t realize that many students prefer nonfiction. We need to do a better job of making teachers aware of the wide variety of titles.

What is different about nonfiction now?

MS: We are really in a golden age of nonfiction. Twenty years ago, there was only one kind of children’s nonfiction, with traditional, survey-style writing. Now we have five distinct forms that also include browsable nonfiction, expository literature, narrative nonfiction, and active nonfiction—such as how-to and activity books.

The genre is blossoming with titles that are beautiful and dynamic, with a range of formats and text structures. They feature rich, engaging language that excites and inspires young readers.

There is so much to offer students that can be used for instruction, read- alouds, book talks, book clubs, and author studies.

Why do you think many young readers prefer nonfiction?

MS: Why wouldn’t they? If adults enjoy it—60 percent of adult books sold are nonfiction—it follows that children would, too. But kids don’t buy their own books, and only 24 percent of children’s books sold are nonfiction. We need to get more great nonfiction books into the hands of children.

The goal is to help kids fall in love with reading and books. For some children, nonfiction is the gateway to literacy. I recommend that educators and parents offer children both fiction and nonfiction and watch closely to understand each child’s preferences.

How can teachers find quality nonfiction titles to offer?

MS: Ask a librarian! The librarian’s job is to help teachers connect a book to a student or lesson. The library is the heart of the school, and the librarian is what makes it beat.

Stewart is developing a nonfiction-focused personal learning community to help educators build students' awareness of and access to nonfiction. Visit melissa-stewart.com.

NEA Report: Teacher Salaries and School Funding by State

Mental Health Care for LGBTQ+ Youth

84% of LGBTQ+ youth wanted mental health care in 2023.

Why Teachers Self-Censor

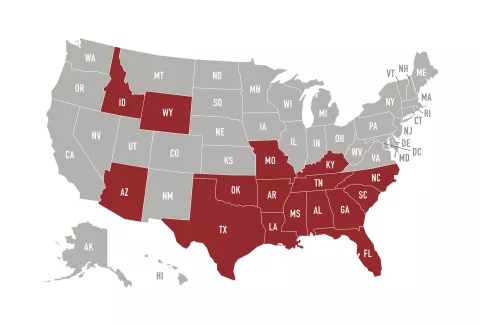

Since January 2021, 18 states have passed laws that restrict how so-called “divisive” subjects, such as racism and LGBTQ+ people, can be addressed in the classroom. These laws impose gag orders on classroom teachers. Even in states where no law has been enacted, some school or district leaders have directed local school systems to adopt restrictive new policies.

But these regulations, and the “culture war” politics that produced them, have far greater reach.

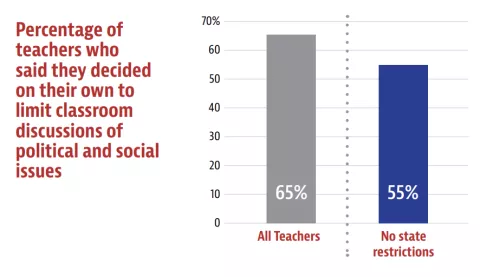

Many educators, fearful over reprisals from community members and a lack of support from school leaders, are deciding to limit instruction in their classroom, or self-censor. According to a RAND Corporation survey released in February, two-thirds of U.S. public school teachers are choosing on their own to limit what they teach.

Furthermore, 55 percent of teachers who do not work under any state or local regulation have chosen to limit instruction. In addition to concerns about upsetting parents, fear of losing their teaching job or license was a top reason for why these teachers decided to take this step.

“We expected that a large number of teachers are taking this step in those states that enacted restrictions,” says Ashley Woo, RAND researcher and lead author of the report. “But when you look at the teachers deciding to do this on their own with no state or local restrictions—and where community support is high—the numbers are surprisingly very high.”

16 States Still Allow Corporal Punishment

The vast majority of schools in the United States—roughly 90 percent—prohibit corporal punishment, but the practice remains legal in 16 states. Major public health organizations oppose its use.

The World Health Organization classifies corporal punishment as a “violation of children’s rights to respect for physical integrity and human dignity, health, development, education and freedom from torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Proponents of corporal punishment argue that inflicting some level of physical pain upon a child deters misbehavior and helps instill discipline. However, extensive research dem- onstrates that the practice has potentially long- lasting negative effects on student’s overall well-being.

Studies show that schools that have used corporal punishment have not been as successful at correcting unwanted behavior as schools that do not use the practice. Students who have been exposed to paddling or other forms of corporal punishment are more likely to exhibit aggression, anxiety, and depression.

In 2023, the American Academy of Pediatrics called for a ban on corporal punishment in school settings and for it to be replaced with practices that better support student behavior.

That same year, U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona penned a letter to administrators and policymakers calling for the ban of corporal punishment in education settings.

“Unfortunately, some schools continue to put the mental and physical well-being of students at risk by implementing the practice of corporal punishment,” said Cardona. “Corporal punishment can lead to serious physical pain and injury. It is also associated with higher rates of mental health issues.”

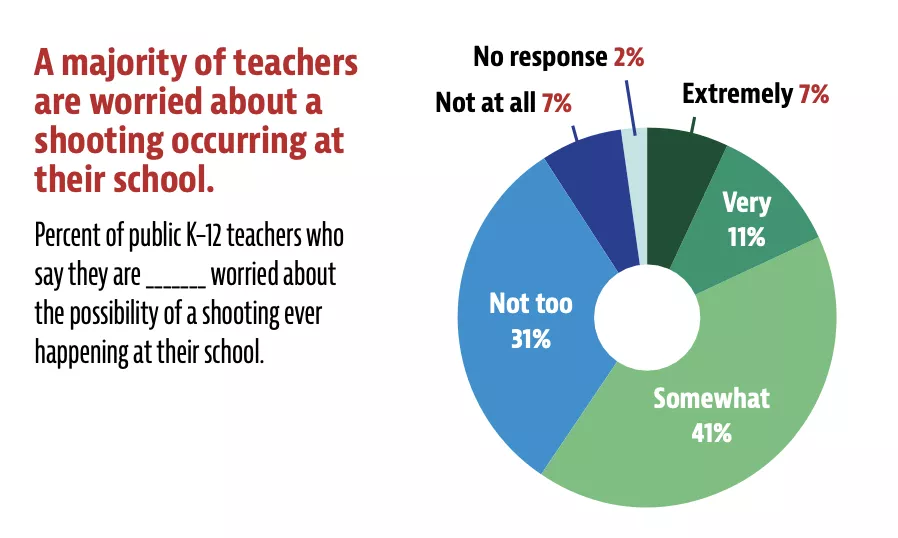

Fear of School Shootings Grows

Twenty-five years after the mass shooting at Colorado’s Columbine High School—and countless more school shootings since—the majority of U.S. teachers (59 percent) are worried about the possibility of a shooting happening at their school, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center. Thirty-one percent of teachers say they are not too worried, and only 7 percent say they are not at all worried.

Source: Survey of U.S. public K-12 teachers conducted October 17-November 14, 2023

Get more from