After treating his first coronavirus patient in the intensive care unit, Nathan Wood—a resident at Connecticut’s Yale New Haven Hospital—recorded himself playing the piano and singing the 1972 hit “Lean On Me.” He said it was a way to manage his mounting stress. But when he heard that the song’s writer, Bill Withers, had died on March 30, 2020, Wood was inspired to share his recording on Instagram.

The post went viral. Soon, the song rang out in nursing homes and hospitals, from windows and balconies, and even in videos made by public school educators. In one post from Cider Mill School, in Wilton, Conn., a seamlessly edited video shows the entire staff singing “Lean on Me” from their homes, while playing everything from pianos and guitars to ukuleles, maracas, flutes, and even a bassoon.

The song became an anthem for the pandemic, when everyone needed somebody to lean on.

During the most difficult year of their careers, when grief and stress became overwhelming, educators recognized that their strength was restored by helping and receiving help from one another. So district by district and around the country, educators reached out across the internet to tell their colleagues, “Lean on me … I’ll help you carry on.”

Educator Sing-Along

‘When You Need a Hand’

The five art teachers of East Maine School District 63, in Cook County, Illinois, used to meet just four times a year. That changed in March 2020, when schools closed and the educators began having weekly Zoom check-ins. They all agree—they’ll never go back to the old schedule.

“Our weekly meetings became a lifeline. Just seeing each other was so important,” says Tina Daskalopoulos, an art teacher at Nelson Elementary School. “It maintained our sense of purpose and, because we were all struggling in the same ways as creative types, we completely understood each other and developed a real sense of unity.”

Colleague Juli Kim, an art teacher at Melzer Elementary School, agrees: “No one will understand an art teacher like another art teacher.”

After school buildings closed, the educators had to reinvent their jobs and became each other’s how-to guides, says Monika Larson, who teaches at Apollo Elementary School. “Each of us has a different teaching style and approach to art education, and we shared individual expertise, solutions, and experiences—like how to use breakout rooms for students in doubled class groups of 50 to 60 students. We shared trials and errors, then we’d go about doing it ourselves, having already sorted through the mishaps.”

The biggest hurdle they had to overcome was getting supplies into the hands of the students. Their school district is located in a Chicago suburb with a large low-income population. One of the educators’ many challenges? Figuring out how to teach art to students who don’t even have crayons or paper at home.

At first, students made art on everything from paper plates to napkins to scrap cardboard. But after the educators created a spreadsheet of materials and their costs, they worked with the district to find the best deals to provide about 2,200 students with oil pastels, permanent markers, large sheets of drawing paper, watercolor sets, tempera cake paint sets, colored pencils, construction paper, and paintbrushes, all of which they procured, packaged and distributed three times during the year.

Another question they grappled with was how to help students who had nowhere to create. Some students logged on from inside cars, underneath bunk beds, sitting on the floor of the family’s convenience store, or surrounded by crates and boxes in what appeared to be a warehouse or factory where a parent was working.

“We shared a lot of concerns about [students’] emotional health and their access to a learning space to sit and log on, let alone create,” Daskalopoulos says.

Student self-expression is essential to social and emotional learning, and it suffered immensely during distance learning. Their students missed walking around the art room and having activity choices and a huge variety of materials for their projects. And that worried their teachers, who knew the students needed a creative outlet, now more than ever.

“Being an art teacher and not being able to create art with our students in person affected all of us,” says Andrew Hancock, an art teacher at Mark Twain Elementary School. “I wanted to be able to help my students bring their creative ideas into fruition, and there was only so much I could do through a screen.”

Educators, thank you for all that you do

To show our gratitude, Zulily is now offering a limited-time 10% discount coupon code to eligible educators through 6/30. Terms and conditions apply — see site for details.

Zulily is an online retailer that offers fashion, home décor and unique finds for the whole family — up to 70% off.

- REDEEM NOW

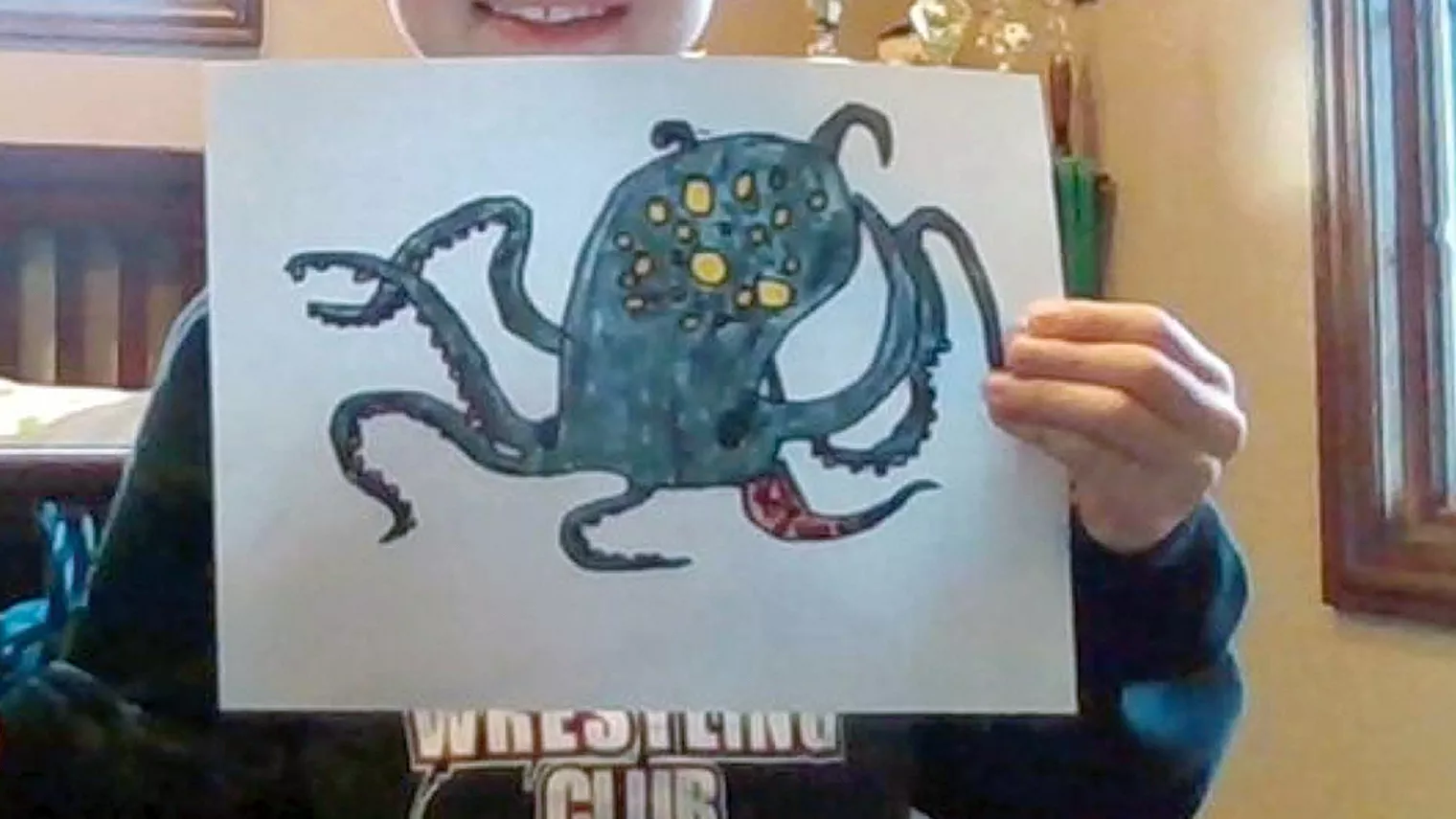

The Octopus Challenge

‘We All Have Pain, We All Have Sorrow’

Like many other educators, the art teachers missed their students and worried about the kids’ welfare. Plus, the teachers had to reinvent their instruction and learn new technology practically overnight. It all led to major stress. On top of that, feelings of isolation and personal and family issues created a pressure cooker of high anxiety.

The group’s weekly check-ins provided an outlet for their fear, confusion, and frustration.

When the district began its hybrid schedule in January, the other teachers returned to in-person instruction, but the specials teachers remained virtual. They hadn’t seen each other, their students, or anyone they worked with in a year.

“A school building, usually bustling with activity, staff in hallways, and the usual small talk was gone, and the quiet and eerie feeling of teaching in an empty room at home was hard,” Larson says. “Seeing my fellow art teachers every week, even on a computer screen, helped filled the void.”

And always hanging over the teachers, of course, was the specter of the virus, which eventually showed up at Daskalopoulos’ door. Her husband and daughter got sick with COVID-19. They recovered, but it left Daskalopoulos badly shaken.

“I don’t know what I would have done without these [colleagues] to lean on,” she says. “We were so united. We’re all at different stages in our lives—one of our teachers was pregnant and another has two little boys at home—but we now understand each other as human beings with more sensitivity.”

‘Just Call on Me, Brother’

It’s no secret that male teachers are in short supply, and though men enter the education profession to make a difference and follow a passion just like their female colleagues, traditional gender roles persist. Some men find it hard to reach out for support, believing that they should be able to handle difficult situations on their own.

“I needed to be confident enough in myself to risk looking like I didn’t know something or to ask for help. I like to figure things out on my own,” says Rick Karmik, an art teacher at Cook County’s Washington Elementary School. “However, in our field, and especially at a time such as this, collegial relationships that are honest and supportive are truly vital to my and any teacher’s success.”

Black men comprise about 2 percent of teachers, and Ohio educator Larry Carey is even more of a “unicorn,” because he teaches pre-K. His stress levels were so high while remote teaching that his hair began to fall out.

“And I have a lot of hair,” says Carey, who teaches at Trevitt Elementary School in Columbus. “I was always thinking, I‘ve got to do this, I have to do that. And then … everything in the news added to the major struggles of teaching young kids on a screen and keeping them from wandering away, on top of [my family] being confined all day in our condo. It was all getting to me.”

Carey knew he needed help, especially when his oldest child, a middle schooler and honor roll student started struggling academically and didn’t even want to go outside with her family.

As a member ambassador of Columbus Early Career Educators, Carey created a much-needed space for male educators to connect, called “Educators Hub: A Discussion for Male Educators.” During a Zoom call with the other men, he felt comfortable enough to share the story of his daughter and her troubles. The others had similar struggles in their own families, and they encouraged him to look into a free therapy program for educators.

“My daughter and I are speaking to one,” he says. “It’s kind of looked down on in the African American community, a Black male seeing a therapist, because some people think it makes you look weak. But in our group, we don’t judge. We treat each other like family.”

Carey also belongs to Ohio New Educators (ONE), a group formed by the Ohio Education Association to help educators in the first 10 years of their careers, when they’re most at risk of leaving the profession. The pandemic worsened the state’s teacher shortage, but the support ONE members offered each other helped many decide to tough it out.

Overnight, they switched from in-person meetings to Zoom calls. And when they launched a Facebook group called ONE Connects, word spread fast. Hundreds joined their Zoom happy hours, dance parties, trivia nights, and professional development sessions.

ONE became a lifeline for preschool intervention specialist Jamie Thompson, who needed family more than ever during the pandemic. Her mother had passed away in November 2019. For a while, Thompson kept herself occupied with union functions in Columbus—about a two-hour drive from her hometown of Steubenville, where she teaches at East Garfield Elementary School.

Then COVID-19 hit. “I went from having my mom, who I was living with, to being on my own,” Thompson says. “I was alone for the first time in 30 years.”

Thompson, who is a member ambassador for ONE and helps coordinate and lead the Zoom events, says she doesn’t know how she would have coped without the group. “I needed the empathy and kindness of my colleagues. It was a lifesaver to just have people to talk to who were going through the same thing.”

She says ONE members are even closer as a group than they were before the pandemic, when all events were in person. Many found it was easier to attend virtual meetings, and they’ve made friends they wouldn’t have made otherwise.

That’s how she met Angela Dolan, a deaf education teacher from Columbus. “I‘d been invited to in-person ONE meetings before, but I was anxious [about attending],” Dolan says. “Being on Zoom felt more relaxed, and the calls allowed me to connect with educators from all over Ohio. Now I’m excited to attend in person to finally meet so many of them.”

Dolan said the ONE meetings made her feel less alone and reassured her that she was still doing a good job as an educator during distance and hybrid instruction.

“It was so refreshing to see so many incredible educators all going through the pandemic together and supporting each other,” she says. “I was able to build friendships that will last beyond this group. I was able to learn more about my union and all that it does for me. I feel like I’m part of a community that I didn’t realize I needed.”

‘I Just Might Have a Problem that You’ll Understand’

Washington was the first epicenter of COVID-19 in the U.S., and substitute support coordinator Aneeka Ferrell, who works in the Renton School District, just outside Seattle, remembers how fear began to spread as quickly as the virus.

“My assistant/substitute specialist, Shantika O’Pharrow, and I were sent home, and we both thought it was for a little while. Then we were told everything is shut down. … Members of our own families were getting sick and hospitalized, and we didn’t know if they’d be OK. We didn’t know what was going on with our jobs, and we didn’t even know what the next day would be like,” she remembers. “It was a lot.”

Five members of Ferrell’s family became severely ill from COVID-19. And as a Black woman, she became painfully aware of how her community was disproportionately impacted by the virus. And then, on top of everything, racial injustices amassed around the country, peaking with the murder of George Floyd, in May 2020.

What Ferrell also didn’t know was that she’d become a pillar to lean on for so many of her colleagues who were grappling with the same issues.

Ferrell conducts trainings on implicit bias for the Washington Education Association (WEA). Before the pandemic, she would travel around the area to give in-person trainings for gatherings of up to 100 educators, who had to juggle work schedules, commutes, and family obligations to attend. When everything shut down, and trainings had to go virtual, she regularly trained hundreds, with hundreds more on a waiting list. Over the course of the pandemic, she has trained thousands of participants.

Of course, Ferrell says, we’re always better together than we are apart, but she felt a sense of purpose, especially helping White colleagues who were struggling to understand the unrest and wanting to know how they could be helpful.

Through it all, she was able to lean on Jill Dahlen, the WEA statewide event coordinator who pivoted from scheduling in-person trainings to setting up virtual sessions.

“I’d talk things through with her, sharing the frustrations but also the benefits of providing this essential service,” Ferrell says. “At first, I didn’t realize how much I benefited from seeing her each and every day. I had her voice and her face to help visually support me. It created a sense of normalcy.”

The benefits of the relationship were reciprocal. Even though Dahlen no longer had state events to coordinate, she was busier than ever with Ferrell, scheduling virtual trainings during a time when educators urgently needed them.

“[Jill] still talks about how it brings her such great joy and how this work gave her a sense of purpose when we were all feeling such helplessness,” Ferrell says. “She is a White educator who is an ally, an accomplice, and now much more than a colleague. She is my friend.”

As summer begins, vaccines are rolling out and a new school year is on the horizon. A sense of renewal is setting in across the country. Friendships forged during the pandemic, like Ferrell and Dahlen’s, will continue to grow and strengthen in person and online.

Thompson says, as soon as it’s safe, educators everywhere will give every one of their school friends, old and new, “a big, giant hug.”

Air hugs may still be the safest for some time to come, but as the song goes, “If we are wise, we know that there’s always tomorrow.”

Resources

Online Learning Opportunities

Social-Emotional Learning Courses

NEA's Social-Emotional Learning courses offer a powerful means to explore and express our emotions, build relationships, and support each other – children and adults alike.

ESP Webinars

Recordings and session materials about supporting ESPs as part of the school ecosystem as we navigate through the crisis and beyond.

School Me Podcast: Building Relationships at All Levels

Shari Collins, a semi-retired training specialist from Omaha, NE, with 33 years of educational experience, discusses building relationships throughout both the classroom and the community.

School Me Podcast: Why Unions Matter for Early Career Educators

Felicia Raney, a language arts teacher from Camden, OH with 21 years under her belt, shares her advice about the importance of union memberships for early career educators and being active in your union.

NEA's Educating Through Crisis

Find information and resources on COVID vaccinations, educators' rights during the pandemic, tips for virtual and hybrid instruction, and ways to ensure our schools are safe and just for all students.

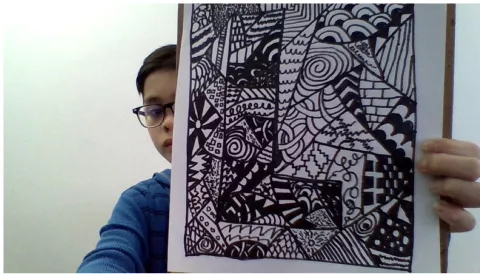

Mindfulness in Art

Storytime with Classroom VIPs

Top photo: The elementary art team from East Maine 63, in Cook County, Illinois, gave each other ideas, support, and a space for venting stress. From left: Juli Kim, Rick Karmik, Tina Daskalopoulos, Andrew Hancock, and Monika Larson.

Safe and Just Schools in 2022 and Beyond

Get more from