Key Takeaways

- After World War II, hundreds of groups targeted public educators in a postwar anti-communist red scare.

- The NEA fought back against unfair criticism of public education through its National Commission for the Defense of Democracy Through Education (commonly called the NEA Defense Commission).

- The story of the NEA Defense Commission is relevant to educators facing attacks today.

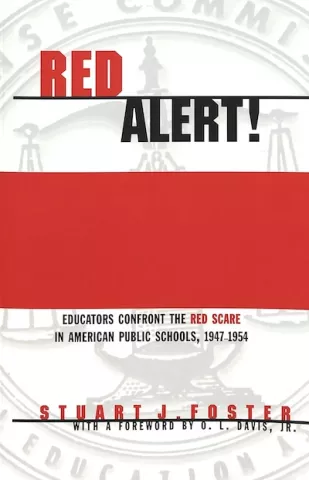

Recent efforts to ban books and to limit how public schools address topics of race and gender have a precedent in attacks on teachers during the 1940s and 1950s red scare. Stuart Foster’s Red Alert!, published in 2001, examines the NEA’s response to red scare attacks. Foster, now Professor of History in Education and Executive Director of the Centre for Holocaust Education at the University College London, spoke with NEA Today about his research and the lessons it may offer to educators today.

What was the NEA’s National Commission for the Defense of Democracy Through Education? When and why was it established?

SF: It was established in 1941 at the NEA National Conference in Boston, and it stayed until 1961. It was very, very busy and active in the period of what we term the “red scare,” the late 1940s through the mid-1950s.

The Defense Commission was set up in June 1941, and this is when Hitler’s tramping through Europe and the [German] invasion of the Soviet Union. So you’ve got this fear of fascism, of communism, of extremism, that is precipitating a lot of this. It gets created as a defense of democracy – the idea of freedom of speech, the importance of liberal values, and so on.

Its simple remit was to defend education against unjust attack, to promote democratic values through education, and I think, importantly, to increase public understanding of education at a time where questions were being asked about progressive education.

It wasn’t a big group of personnel at the NEA, but it was quite high-level. It had a committee of ten people that met regularly, and the NEA president was always one of the ten people.

What were some concrete things that the NEA Defense Commission did to defend the teaching profession and public schools during the 1940s-50s red scare?

SF: First is obviously responding to anti-communist attack, and particularly the plethora of organizations that sprung up during this period, the late 1940s and early 1950s. I was absolutely amazed by the scale of these organizations. The NEA calculated there were over 500 active anti-communist groups that were attacking teachers and attacking education in various ways. [One example], the National Council for American Education, was led by a guy named Alan A. Zoll, and his organization was everywhere, all across the country, challenging progressive education, challenging the racial integration of schools, challenging rises in taxes, calling out teachers for being “commies,” “pinkos,” you name it. This was a large-scale issue, and the NEA was recognizing the need to track and challenge these organizations at the local, state, and national level.

[Second], the Defense Commission had a newspaper called the Defense Bulletin. These defense bulletins were a recording of what was going on around the country.

I think another thing was this idea of PR. [The Defense Commission] put a lot of energy into making lay people outside of education understand and appreciate what educators were doing and what was going on in American schools. There was a PR campaign to say, “back your schools; back your teachers,” and there were opinion pieces in newspapers, there were radio interviews, there were records and movies and sound recordings.

There was an NEA campaign in the early 1950s called “Better Schools Make Better Communities,” and the NEA paid for 10,000 posters to go on bus shelters and in town centers around the country as part of that program. There were conferences with business groups, with local community groups, [and] with teachers’ unions that tried to establish and build a network of support for schools, and the Defense Commission was heavily involved in them. In 1953 they set up one called “Public Education in a Dangerous Era,” and this was very much on the idea that schools were under attack. These conferences were in places like San Francisco and Denver, Oklahoma City, New York City, and attracted large audiences.

The fourth thing was boosting confidence and well-being of teachers, [telling teachers] “There are people to defend you, to protect you.” They even had a small amount of money in the defense fund that if teachers were attacked and they needed legal fees or legal support, the Defense Commission was able to offer some of that. I think it was a great credit to the NEA that they were able to buttress the support for schools and educators in that way.

The fifth one was quite niche, which was particular and peculiar to the NEA. They conducted investigations. They would have a team go in, led often by Robert Skaife, who was the field secretary, to a particular city or town where there were red scare attacks.

Do you have any critiques of the NEA Defense Commission? Could they have done anything differently?

SF: I remember at the time [of writing the book] thinking a lot about this, because that thesis that the NEA could have done more – that’s easy for an academic to say. I think it would be unfair to be too critical of the Defense Commission, given its budget, given its resources, given its staff.

But I still think it holds that they were a creature of the red scare age. I think there is this sense that something becomes normalized because it’s so common in the media – the idea there are communists infiltrating higher echelons of government, that they are infiltrating our schools. So although I criticize the Defense Commission and some of the NEA membership [and] leadership for buying into that and playing ball with that kind of rhetoric, you also have to understand why they would do that.

In 1949, the NEA passed a resolution to ban communists from being in the teaching profession. Now for a lot of people, that’s a very reasonable thing. But it’s the idea of “Who is a communist,” you know? If you had leanings towards left-wing politics, or a friend of yours used to be a member of the Communist Party - [it becomes] a very gray area. Of course they’re doing it because they want to seem to be a democratic, responsible organization. But what that led to was people being identified as communists who almost certainly weren’t in many occasions.

If you take the issue of loyalty oaths – in the late 1940s, I think twenty-nine states had loyalty oaths, and that grew with HUAC and the loyalty investigations at the state and federal level. The NEA took the position that they never told teachers not to sign an oath, and they told them to completely fulfill the obligation of going to the investigations and giving testimony. You could argue, “Don’t sign the oaths. If we all don’t sign the oaths they have to take us all on.” You could say, “We won’t support these witch hunts, these loyalty investigations unless they’re conducted in a certain way.”

The NEA was very clear they didn’t like [loyalty oaths]. They were very clear that they opposed them, very clear that they felt they were misguided and sometimes unjust and unfair, and they were quite robust in their criticism. But [the NEA] never said, “Don’t participate; boycott them.” But it’s easy for me to say, sitting in my house in England, what they should have done.

Also, the Defense Commission had a budget in 1952 of $72,000 [editor’s note: this would be about $850,000 in 2024]. The revenue for the NEA was $2.75 million [ed: roughly $32.75 million today]. So in some ways it had a small budget – and you could argue if the NEA was really serious about tackling and addressing [the red scare assault on education], it should have put more resources and more time and more personnel in.

What is one compelling story or anecdote that sticks with you from your research for Red Alert?

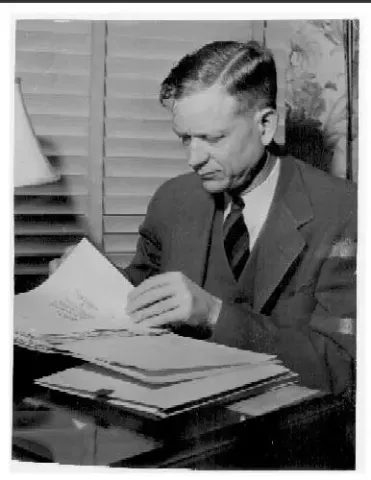

SF: In Pasadena in 1948, they had just appointed Willard Goslin to be school superintendent. Goslin was the president of the American Association of School Administrators. He was extremely well-respected, and he was head-hunted to go to Pasadena as the school superintendent. I describe him in the book as an educational king. But Goslin gets hit by the red scare, and he loses his job.

The story of Goslin stuck with me. Here’s a guy that’s got an incredible reputation. Incredible CV. Very well-respected. He went into a difficult situation in Pasadena – difficult because they were wrestling with post-war issues of growing population, low taxes, and they needed to get more investment in schools. You’ve got issues of rezoning and racial integration.

Very quickly he’s trying to get taxes to be raised, he’s talking about rezoning educational districts, and it just goes into this frenzy of criticism and all the red scare organizations start chiming in. They come, and they almost camp out in Pasadena to take this education king – Willard Goslin – out.

And of course, the guy basically is just trying to be a bit more progressive and a bit more open and just raise tax dollars. And he’s doing nothing at all which is subversive. I mean, there’s an example where he promoted some camping trips and [red scare organizations] were pointing to it to say, “Well, that’s what the communists do, they have camping trips, collectivization.”

It was nonsense, but it just kept coming, and in the end he’s forced to resign. By the summer of 1951 he’s out. And this story stuck with me because most of this was a manufactured crisis. It goes to show the power these red scare groups had.

What are some of the common themes that you’ve noticed in the culture wars that impacted U.S. public schools over the past century? Have you noticed more and less effective ways for teachers and teachers’ unions to fight back against assaults on their profession and their autonomy?

SF: First, I think it’s a strange thing to say, but [the red scare] really wasn’t about rooting out communists. It’s almost that the rhetoric and the context were used as a weapon to discredit people with whom you didn’t agree. I think that with culture wars, you heighten up this whole rhetoric of “We’re under attack! These people are undermining us!” The rhetoric is so extreme and so damaging. But it’s actually about discrediting opposition.

I think culture wars are also about setting an agenda. There may be more important issues, but because it’s heightened, because it keeps being brought up, it becomes the issue.

In terms of fighting back, I think [there’s] great importance in building coalitions to support the schools and teachers in communities amongst politicians, laypeople, businesses – making the public aware of what we do. Also, the importance of unity and solidarity – that point of supporting teachers, of looking after their well-being and welfare, celebrating their achievements, valuing teachers. Teachers wrote letters to the Defense Commission appreciating the support [the Commission] gave them.

A third would be the importance of defending academic freedom and the right for people to discuss controversial issues in a thoughtful, rational way. The two other things I would add would be to quash the criticism early. Pasadena is a case-in-point where [the Defense Commission] came in late, and the damage had been done. Last, if you really believe in the importance of supporting teachers and supporting academic freedom, you need to put resources into it. You need staff. You need the communications, the PR. All these things are time-consuming.

And I suppose the overarching lesson from the red scare: don’t accept the foundations, the basic tenets of the critcism.