The bottom line on student learning today is this: “You can’t teach if you’re not addressing mental health,” says Rene Myers, an intervention specialist in St. Paul, Minn.

Myers has been working in public education for more than 33 years. Over the decades, the mental health needs of her students have grown, and grown, and grown, she says. The pandemic, coupled with decades of inaction by school boards and state legislators, has only made things worse.

About 214,000 U.S. children have lost a parent to COVID-19. They’re adrift, grieving. Many other parents and caregivers lost their jobs. Today, 17 million U.S. children struggle with hunger—about 6 million more than before the pandemic. On top of that, recent years have reinforced how much this nation still struggles with racism and antiLGBTQ+ hatred.

So when Myers sat down at the bargaining table this year, seeking to negotiate a new contract between the St. Paul Federation of Educators (SPFE) and her school district, her number-one priority was students’ mental health.

“To know what our students and staff have gone through in the past two years … to say we don’t need mental health supports? It’s like saying you don’t need air. It’s unimaginable!" she said.

In February, St. Paul educators voted to strike. Then, in early March, just hours before hitting the streets, union negotiators reached an agreement to preserve the mental health teams that SPFE won during 2020 bargaining. Those teams include counselors, nurses, social workers, and school psychologists in every St. Paul school.

These professionals are essential to providing students with what they need, says Myers.

From Bad to Worse

In the past year, even as the nation has returned to “normal” life, the latest research shows that many students are still living in a state of mental health crisis. This data isn’t at all surprising to educators and parents.

“Of course we see advanced need! On top of the pandemic, everything happening with the economy also is impacting our families,” says Theresann Pyrett, a Michigan middle school teacher and president of the West Ottawa Education Association (WOEA). “It’s like a perfect breeding ground for mental health issues to develop.”

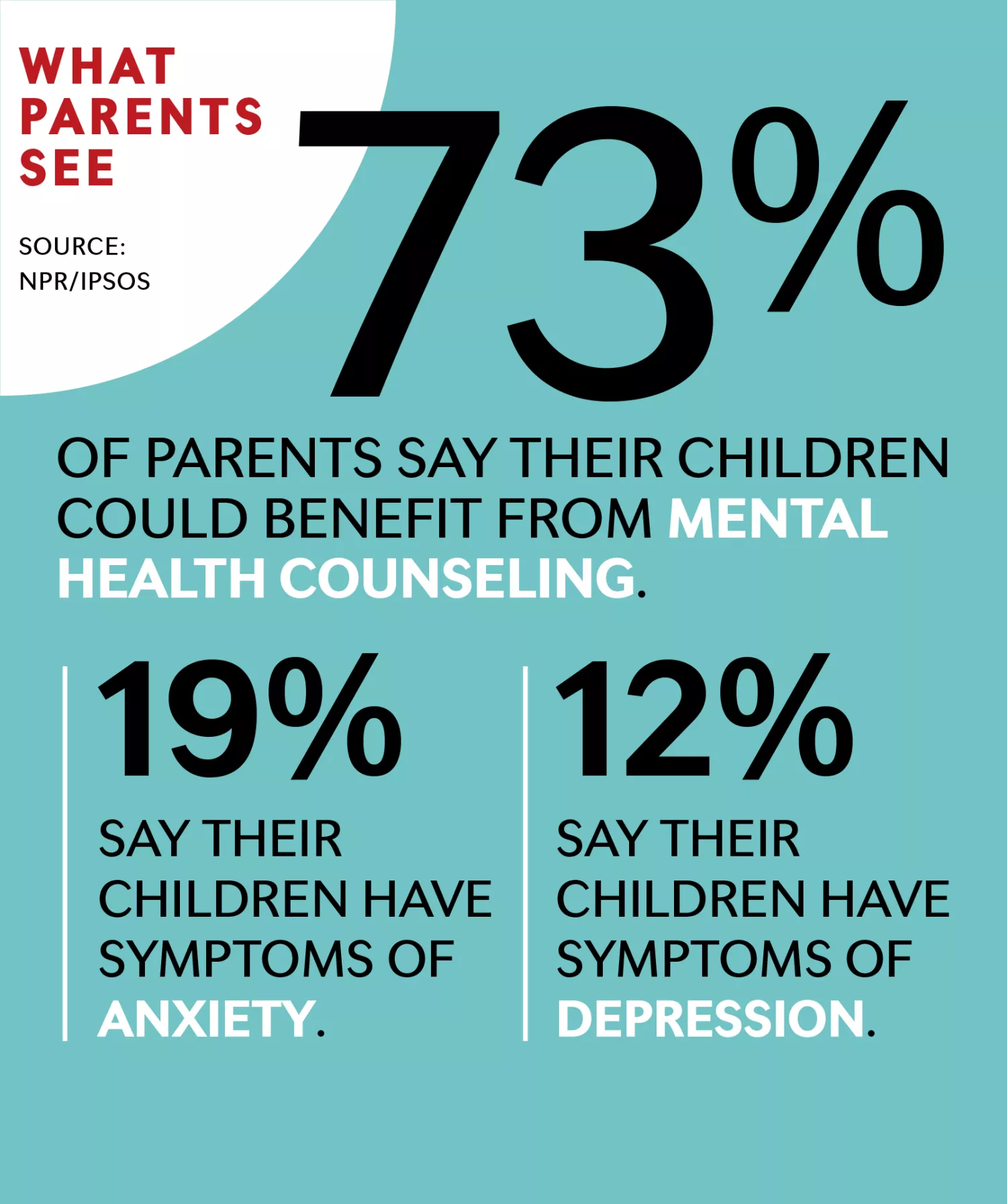

In an April poll, nearly three-quarters of U.S. parents said their child would benefit from mental health counseling—up from 68 percent in 2021. Additionally, about a third said their child has recently shown symptoms of mental health issues, including anxiety (19 percent) and depression (13 percent).

Among parents of students with disabilities—including learning, developmental, and physical challenges—almost a third said their child has anxiety, and rates of depression are higher as well.

“The biggest misconception is that COVID makes people mentally ill. From my point of view, COVID unmasked people who have underlying vulnerabilities,” said John Walkup, chair of the behavioral health department at Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital, in an interview with the New York Times.

Before the pandemic, between 2016 and 2019, the number of children diagnosed with anxiety rose by 27 percent, while depression diagnoses rose by 24 percent. But recently, it’s worse than ever.

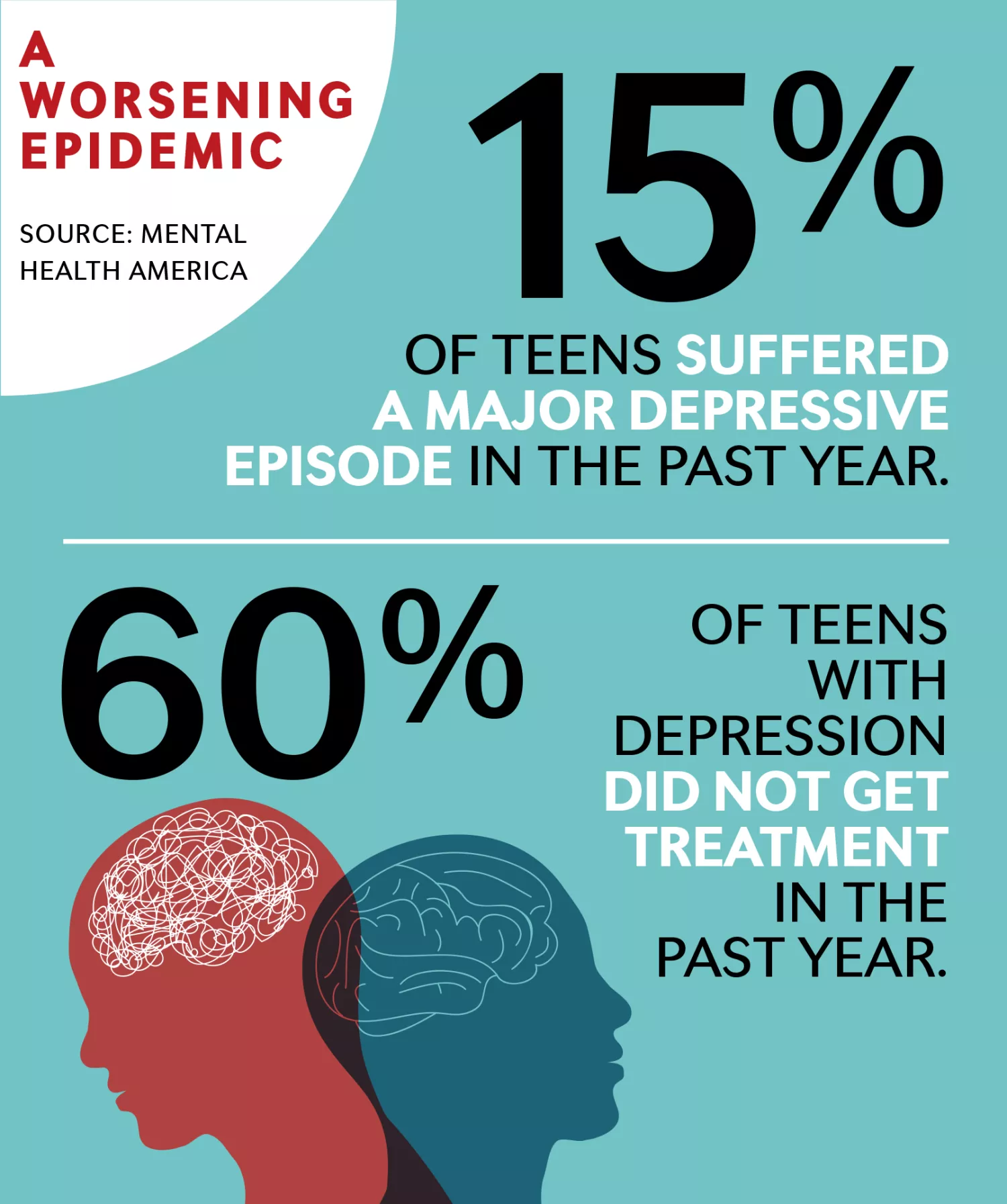

In the past year, 15 percent of teens suffered at least one major depressive episode—that’s an additional 306,000 teens over the previous 12 months, according to the 2022 data from Mental Health America. On top of that, nearly two-thirds of teens with major depression say they haven’t gotten any help.

Demanding Help for Students

In West Ottawa, the local union is making sure students get what they need. That includes using local property tax revenues to hire 10 additional mental wellness coaches throughout the district and using federal pandemic relief funds to hire 16 additional interventionists.

WOEA leaders work closely with district administrators, all asking the same question: What’s best for students?

“One thing I keep repeating, over and again, is that more hands on deck makes for a lighter load,” Pyrett says. “We’re focused on picking up kids—and if you have more hands to pick those kids up, it’s so beneficial for those kids.”

The Biden administration’s pandemic relief plans have made the largest-ever, single investment in public schools. Now educators are making sure that money is used for the counselors, social workers, school psychologists, behavioral coaches, etc., that students need to be successful.

Unions also are bargaining contracts that include those supports. In Minneapolis, educators went on strike this spring for more than two weeks, finally settling a deal that doubles the number of nurses and counselors in elementary schools and provides a social worker in every school.

"Don't Say Gay" — Or Trans, Either

Maybe the most alarming figure in recent mental health data is this: Nearly half of young LGBTQ+ people have considered ending their lives in the past 12 months, according to a survey of 34,000 young people by the Trevor Project.

Among those young people with suicidal ideas, more than half are transgender and nonbinary youth and nearly half are Black. (Nonbinary is a term for people who do not identify as male or female.)

The numbers are troubling, but not surprising to Palm Beach County, Florida high school teacher Michael Woods. “Especially here in Florida, with the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ law, which should also be called ‘Don’t Say Trans,’ we have a lot of kids in stress,” Woods says. “They’re just coming back to the rigors of school [after the pandemic]—and now this!”

The Florida law enables parents to sue school districts if they think their child has had inappropriate instruction on gender and sexuality. The cost of litigation will be borne by districts, which are already beginning to remove curricula on these topics.

Anti-gay laws are also spreading far beyond Florida. In Texas, Gov. Greg Abbott has ordered teachers to report parents of transgender youth for child abuse if the parents seek gender-affirming care for their child. NEA and state educators unions have spoken out against these laws.

For his part, Woods—an educator of 29 years—isn’t afraid. He wears his “We’re All Human” T-shirt and answers his students’ questions. But he worries about younger teachers with less job security, living in more conservative areas.

“I tell the kids, I’m always here for you. I’m always a safe space for you. I’m not giving up on you, and you shouldn’t give up on yourself,” he says. “When young people don’t feel like they have anywhere to turn or anyone to talk to … well, I know why the stats are the way they are.”

What Can You Do to Help?

NEA has resources for you!

Go to nea.org/ mentalhealth to take these steps and learn more:

Step 1: Email Congress. Ask for more mental health supports in schools and more funds for community schools, which provide additional services to students and families.

Step 2: Learn how to build social and emotional skills in students and take care of yourself, too.

Step 3: Work with your local union. The Biden administration’s historic investment in public schools has created the opportunity for more spending on mental health professionals and services in schools. Local unions that engage in collective bargaining can negotiate these sup - ports into their contracts.