Key Takeaways

- Creating inclusive classrooms requires understanding the difference between cultural appropriation and appreciation.

- Educators should avoid using stereotypes and teach cultural practices with respect and understanding.

- Teaching students to think critically fosters empathy and respect for diverse cultures.

Over 350 languages are spoken in homes across the U.S., reflecting the rich cultural tapestry in today’s public schools. As classrooms become more diverse, the need for educators to create inclusive environments that honor and mirror the backgrounds of their students while fostering mutual understanding and respect has never been more pressing. Key to this is distinguishing between cultural appropriation and appreciation.

What’s the difference?

Cultural appropriation happens when elements of someone else’s culture are taken and used in a way that strips away their original meaning or disrespects their importance. It can often lead to the exploitation of other cultures. Appreciation, on the other hand, means someone takes the time to understand and honor the culture, often involving collaboration with people from that background.

Take, for example, Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead. This is a holiday that celebrates life, death, and family. It’s observed in Mexico and other places, including the United States. If people are interested in celebrating this day, it’s not simply a matter of painting a sugar skull or dressing up as a Catrina, a central symbol of the holiday. Instead, they should learn about its significance as a day to honor loved ones who have passed away and consider creating an ofrenda (offering) with real understanding of its symbolism.

And so, how does this filter down into classrooms?

Recognizing the line between respect and harm

“Stereotypes are still present in classrooms,” says Tucker Quetone, a retired English teacher and now a Native American liaison for Rochester Public Schools, in Minnesota. “I see it in textbooks, on school walls, and even in grade school activities like coloring pages,” adding that this perpetuates outdated and harmful ideas.

He’s seen, for example, the misuse of sacred traditions, such as an educator asking students to pick their "spirit animal" or leading an activity where students create dreamcatchers or Southwestern sand paintings. Using “spirit animal” casually, for example, is often considered cultural appropriation because it trivializes its deep spiritual significance in Indigenous culture—where animals serve as sacred spiritual guides tied to specific tribes and traditions.

“Teachers need to understand that these items have deep cultural and ceremonial significance. Making dreamcatchers in class can trivialize their meaning,” he explains. Sand paintings, for instance, are very sacred and have to do with ceremonies. Even drumming—you need to be careful because tribes have certain protocols on who can drum.”

Celebrating culture thoughtfully

When it comes to cultural appreciation, Quetone shares an example from his time in Rochester.

“We focused on traditional values of local tribes like the Ojibwe, Anishinaabe, and Dakota, such as honesty, respect, and courage. These values were tied to icons—like a turtle or eagle—and [exhibited] on posters in English and the Native languages. This approach celebrated the culture without crossing boundaries,” he shares.

His advice to avoid classroom practices that perpetuate stereotypes or strip traditions of their deeper meaning is to start local.

“Engage with Native students and their families or consult nearby tribes to determine what is appropriate to share in the classroom," he advises.

For Quetone, another critical element to celebrating Indigenous culture is to focus on Native people who are still here, practicing their language, culture, and traditions.

“We’re a part of the modern world,” he says. “We want to be part of the curriculum, but we want that to be done in a respectful way—not just historically.”

Going beyond the basics

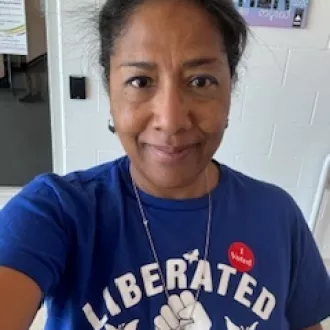

Cassandra Sheppard, a social studies teacher, who teaches critical ethnic studies, in Saint Paul, Minn., explores cultural appreciation in various ways and throughout the year.

She recalls a classroom discussion focused on culture and power, where a famous singer wore traditional Hmong jewelry with a revealing outfit, sparking conversation about cultural appropriation.

The students debated whether it was done out of ignorance or intentionally without respect for the culture’s origins. This led to discussions about solidarity and how students can stand with communities facing such issues.

“I always remind [students]: ‘It’s a big deal to do stuff for us but not without us,'" says Sheppard.

Sheppard adds another layer to this topic by emphasizing the importance of creating a sense of community in classrooms.

“Having kids not feel like they have to be the sole voice for their culture is huge,” she says, explaining that “when we talk about different aspects of culture, especially cultural stereotypes, I ask, ‘Have you ever heard this before in your life?’ Some students have, and some haven’t, and this opens up authentic discussions without making blanket statements.”

The goal for students is for them leave her classroom with some critical consciousness.

“I want them to be able to assess the world and … make it a better place for themselves, their families, and their community,” she says.

Building inclusive classrooms

For Kimberly Colbert, a high school English teacher, who also teaches ethnic studies, in Saint Paul, a key point is the prioritization of cultural literacy among educators.

Quote byKimberly Colbert , High School English Teacher

As a Black and Asian educator, with 30 years of teaching experience, she underscores that instead of relying on outdated classics just because they’ve always been taught, to instead look for diverse narratives that resonate with today’s students.

Colbert also emphasizes the need to frame historical narratives in empowering ways.

In her African American literature class, for example, students read excerpts from “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” as well as Colson Whitehead's “Underground Railroad.” She organizes the readings under themes, such as Black strength, Black creativity, and Black ingenuity. This approach counters the narrative of perpetual oppression and instead celebrates resilience, she says.