Key Takeaways

- Title IX, a federal civil rights law, is intended to guarantee equal access to education for all students. But it's often not working for victims of sexual violence.

- Four out of 10 students who report sexual violence to their schools also suffer "substantial disruption" in their education, meaning they're forced to transfer schools, take time off, or drop out.

- Advocates say this will only get worse if the Trump/DeVos rewrite of Title IX regulation isn't undone. In April - Sexual Assault Awareness Month - the Biden administration announced a comprehensive review of those regulations.

Even as Title IX, a federal civil rights law, aims to make all students feel safe and equally able to access education, a recent report shows how survivors of sexual violence often suffer more harm when they report their assaults and attempt to get help.

Four out of 10 students who formally reported sexual violence to their high schools or colleges experienced “substantial disruption” in their educations, according to a survey administered by Know Your IX, a survivor- and youth-led project of Advocate for Youth, which published “The Cost of Reporting: Perpetrator Retaliation, Institutional Betrayal, and Student Survivor Pushout.”

Survivors describe how they feared attending class with their rapists. Some were told by their schools that it was their responsibility to stay away from their attackers. While some switched to online classes or changed their majors, 39 percent took a year of absence, transferred or dropped out of school altogether. Meanwhile, more than a third of survivors were told by their schools to “take some time off.”

Survivors also struggled with financial, career and health impacts, and backlash from attackers, including retaliatory, defamation lawsuits. Making matters even worse, they often were re-traumatized through the Title IX reporting and investigating process.

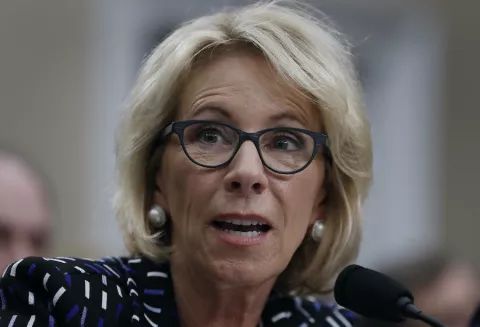

Advocates say this will only get worse for survivors, if the Trump/DeVos administration’s rewrite of Title IX regulations, which went into effect in August 2020, isn’t undone. Their changes, which include the opportunity for rapists to cross-examine their victims, through an advocate, were vigorously opposed by NEA, which submitted a detailed, 12-page letter of objection to former Education Secretary Betsy DeVos in 2018.

President Biden has promised to reverse the Trump/DeVos regulation, and last month, he ordered the Department of Education (ED) to conduct a comprehensive review of Title IX regulations. (Biden also created the Gender Policy Council to prevent and respond to gender-based violence, among other things.) However, formally rewriting the Title IX regulations, like DeVos did, is a process that will take years.

What is Title IX?

Since 1972, Title IX has ensured that girls and women have equal access to education in schools and colleges that receive federal funds, which is all public K-12 schools and almost all colleges, regardless of whether they’re public or not. Maybe best known for paving the way for women athletes, the law also makes sure girls and women have equal access to academic offerings and on-campus housing—and that they are safe from sexual harassment and assault.

More than one in four undergraduate women experience rape or sexual assault through violence or incapacitation, according to a 2020 report. But the numbers could be even higher than that—more than 90 percent of sexual assault victims on college campuses don’t report their assaults, reports the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

Under the law, when a student reports an assault, their school is obligated to take measures to make them feel safe on campus so that they can equally access their education. “In other words, schools are bound by Title IX to help make sure sexual violence doesn’t push a survivor out of school,” notes the Know Your IX authors.

"I was in class with the perpetrator of my rape. I was unable to attend this class without flashbacks and had to take it as an independent study. My grades dropped significantly as I became afraid to leave my dorm room as he was still on campus." - student survivor (“The Cost of Reporting" by Know Your IX)

This seems like a clear-cut mission, but during her tenure DeVos embraced so-called “men’s rights” advocates who said it went too far. Her changes to Title IX regulations include: narrowing the definition of sexual harassment that requires schools to ignore misconduct until it becomes “repeated and severe;” the exclusion of off-campus conduct (such as the well-known Brock Turner rape case at Stanford); and new requirements for Title IX grievance procedures, including the cross-examination of victims.

Additionally, while the pre-DeVos guidance advised colleges to use a “preponderance of evidence” standard, meaning allegations would be proven when schools find it’s more likely than not that harassment or abuse occurred, schools now must find “clear and convincing evidence.” The new standard encourages mini-trials, giving an advantage to wealthier perpetrators who have the money to hire their own attorneys.

In its review of the DeVos rules, NEA called them dangerous. Incidents of sexual harassment and violence already are known to be under-reported, and advocates anticipate the new rules will make it even less likely that victims will come forward. Who wants to relive the trauma of their assault through the cross-examined of their rapist?

The Consequences of Reporting

Title IX is intended to protect educational access in the wake of sexual violence, but the survey found that this isn’t happening. Survivors often miss out on learning, and the survey shows how much work schools still need to do.

One survivor reports telling her professor that she was struggling with the aftermath of sexual violence. His response? “Well, we are all going through something.” Similarly, when a high school survivor told her counselor that she was uncomfortable being in the same room as her perpetrator for meetings related to their shared specialized program, the counselor recommended dropping out of the program, “if she couldn’t handle it.”

Financial consequences also are common. When one survivor dropped a class she shared with her abuser, she had to pay $500 to retake it. Another survivor reports losing their scholarship when they transferred to avoid their abuser, while even others point to increased student debt from re-taking classes. Graduate students, in particular, face financial constraints, especially when their abusers are also their employers, advisors and professors.

And then there are the mental-health costs. More than 40 percent of survivors disclosed that they suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and more than a third experience anxiety. Nearly 15 percent mentioned panic attacks and the same percentage brought up suicidal attempts or suicidal ideas.

The process of reporting and surviving can be as traumatizing as the original incident of sexual violence, survivors reported. This includes extensive victim-blaming, discouragement from reporting, and procedural issues that lead to broken trust between survivors and schools. One survivor was told by a Title IX coordinator, “if you don’t want to report it and ruin his life, you don’t have to.”

After coming forward, 15 percent of survivors say they faced or were threatened with punishment by their schools. Of them, nearly two-thirds either took a leave of absence, transferred schools or dropped out. When one high-school student was sexually assaulted on a field trip, “the field trip sponsor blamed me and told me that if I reported the student, I would lose my officer position and no longer be allowed to travel with the organization for competitions.” Meanwhile, a graduate student reports, “Ultimately I was dismissed from the [Master's of Social Work] program for ‘unprofessional conduct,’ including leaving the classroom when I was triggered by hearing my perpetrator’s voice.”

One survivor told researchers, “Honestly, what the school did to me was worse than what my rapist did to me.”

The report also notes a disturbing increase in retaliatory “cross-filings” by attackers, which can include defamation lawsuits or frivolous complaints. Wealthy attackers, in particular, have a new advantage: “Because they hired a lawyer who specialized in suing institutions, the university caved and let my abuser skip out on the punishment that was mandated at the end of the Title IX case,” reports one survivor.

Where Do We Go from Here?

While a comprehensive rewrite of the regulation could take years, Education Secretary Miguel Cardona announced earlier this month that the ED has committed to three actions in the near future:

- Publishing a Q&A on their interpretation of the regulation and highlighting areas where schools have discretion under the rule.

- Hosting a virtual public hearing to obtain feedback on the regulation.

- Proposing amendments to the regulation through the rulemaking process.

Meanwhile, "The Cost of Reporting" also includes extensive recommendations to improve the process. Some of these include enhanced mental-health services, funded through local, state and federal governments. This is particularly important for K-12 students, who often said their counselors didn’t have enough training in sexual violence.

"When I started having severe panic attacks because of his presence on campus, they forced me to drop all my classes. I tried to re-enroll for the next semester but couldn’t do it and left for good over spring break." - student survivor (“The Cost of Reporting" by Know Your IX)

Survivors must be accommodated in their schools and on their campuses—in residence and dining halls, and in classrooms, the report's authors say. Survivors should be able to withdraw from classes, if they choose to, without penalty.

And discipline processes need to be fair, unbiased and equitable. This includes timely and clear notice, the opportunity to review evidence, access to counsel, and more. Any cross-examination should be done through a neutral third-party, after the questions are reviewed by a panel of impartial, trained decision-makers.

“Survivors have been forced out of school, been punished for being raped or speaking out, lost thousands of dollars, died by suicide, and been killed by intimate partners after their schools refused to take action to keep them safe,” the report’s authors note.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. “Together, we can build a world where the promise of Title IX—that students be able to learn free from violence and its impacts—is not just a right on paper, but also in reality,” they wrote. “Because the cost of an education should never include sexual violence.”