Key Takeaways

- Since the enactment of universal school voucher programs, states are struggling with the programs’ cost and lack of transparency and accountability.

- Overwhelmingly, school vouchers are being used by families with children already in private school to subsidize their tuition.

- Voucher programs’ skyrocketing costs will divert funding not only from public schools, but also other critical public services.

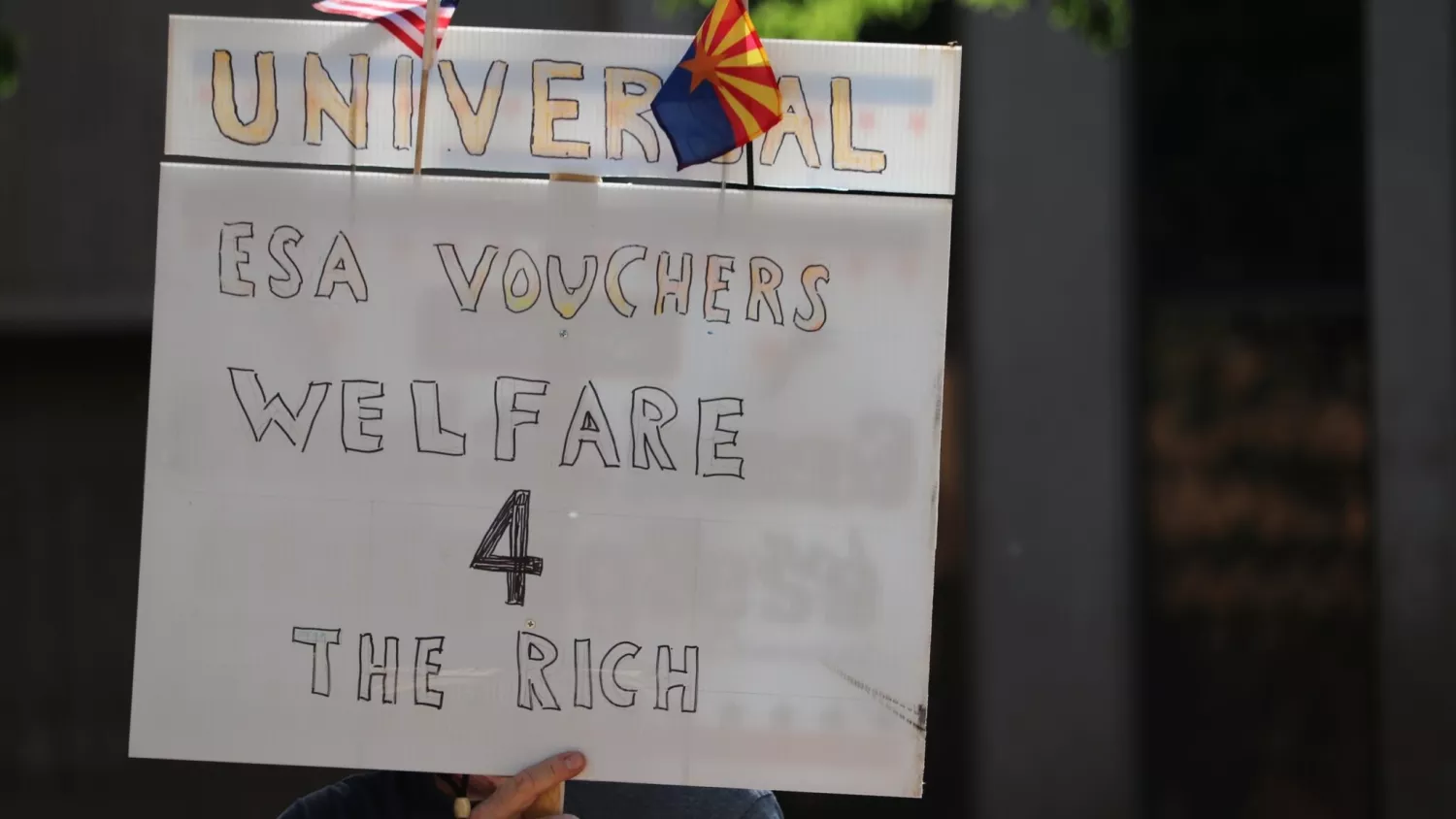

In December 2022, Arizona became the first state in the nation to enact a universal school voucher program. The Empowerment Scholarship Account (ESA), as it is called, provides roughly $7,000 of taxpayer dollars per child to cover a wide array of broadly defined “educational expenses,” including private school tuition, home-schooling, and other private expenses—with very few strings, if any, attached.

Enrollment has skyrocketed, quickly surpassing 70,000 students by the beginning of 2024.

While it may still be growing, Arizona’s ESA voucher program is also a fiasco. All the promises made over the past year by the law’s most zealous supporters have run aground amid reports detailing the program’s astronomical cost and lax accountability. Voucher laws generally do not require any sort of disclosure from private schools about their finances, how they operate, or how they measure student achievement. Arizona’s is one of the least accountable voucher programs in the nation.

Recent audits revealed that private school parents, and now voucher recipients, have used the funds for a slew of, at best, questionable expenses, including kayak lessons, horseback riding lessons, home gyms, televisions, and more. Earlier audits conducted prior to the most recent expansion revealed similarly questionable uses.

Why private school parents? Because that is who the program has mainly benefited. The funds are being used predominantly by families whose children are already in private school. Far from saving money as promised in 2022, school vouchers are proving to be a budget-buster.

No one should be surprised about any of this, says Marisol Garcia, president of the Arizona Education Association, which has led the opposition to the voucher program in the state since its initial introduction in 2011. “There has been no accountability, no transparency,” says Garcia.

For school privatization advocates, the lack of oversight and other failings are a feature, not a bug.

“These lawmakers don’t care about the strain on the budget or what this does to our schools and our communities,” says Michael McGowan, a high school teacher in Glendale. “It’s just an attack on public education. Taking money out of the system, draining resources, weakening our schools— that’s the point.”

Bankrupting the State

Under an ESA, a portion of a state's per-pupil education funding is put into an account that parents can tap into to pay for generously approved education expenses, including private school tuition.

ESAs are merely “Vouchers Plus,” Josh Cowen, professor of education policy at Michigan State University, recently wrote. “They’re similar in nearly every respect— “plus” in the sense that allowable expenses include not only private tuition but other education-related items.”

Arizona’s ESA voucher program was first enacted in 2011, but it came with eligibility requirements that limited access to students with disabilities. In 2022, the program became universal, available to every student in the state. The Republicans running the legislature helped sell universal vouchers under the ruse that they would help low-income students.

When it was being debated, educators and community organizations urged opposition to the program. They warned that far from serving lower income families, vouchers would serve private school families, siphon valuable funds from public schools, and disrupt and destabilize the state budget.

All of that, and more, has happened across the state.

A 2023 analysis revealed that most universal ESA recipients in Arizona live in areas with median incomes ranging from $81,000 to $178,000. Just 5 percent come from ZIP codes where the median income is under $49,000.

An earlier Grand Canyon Institute report found that 80 percent of voucher applicants did not attend a public school, meaning they were are already attending private schools or being home schooled.

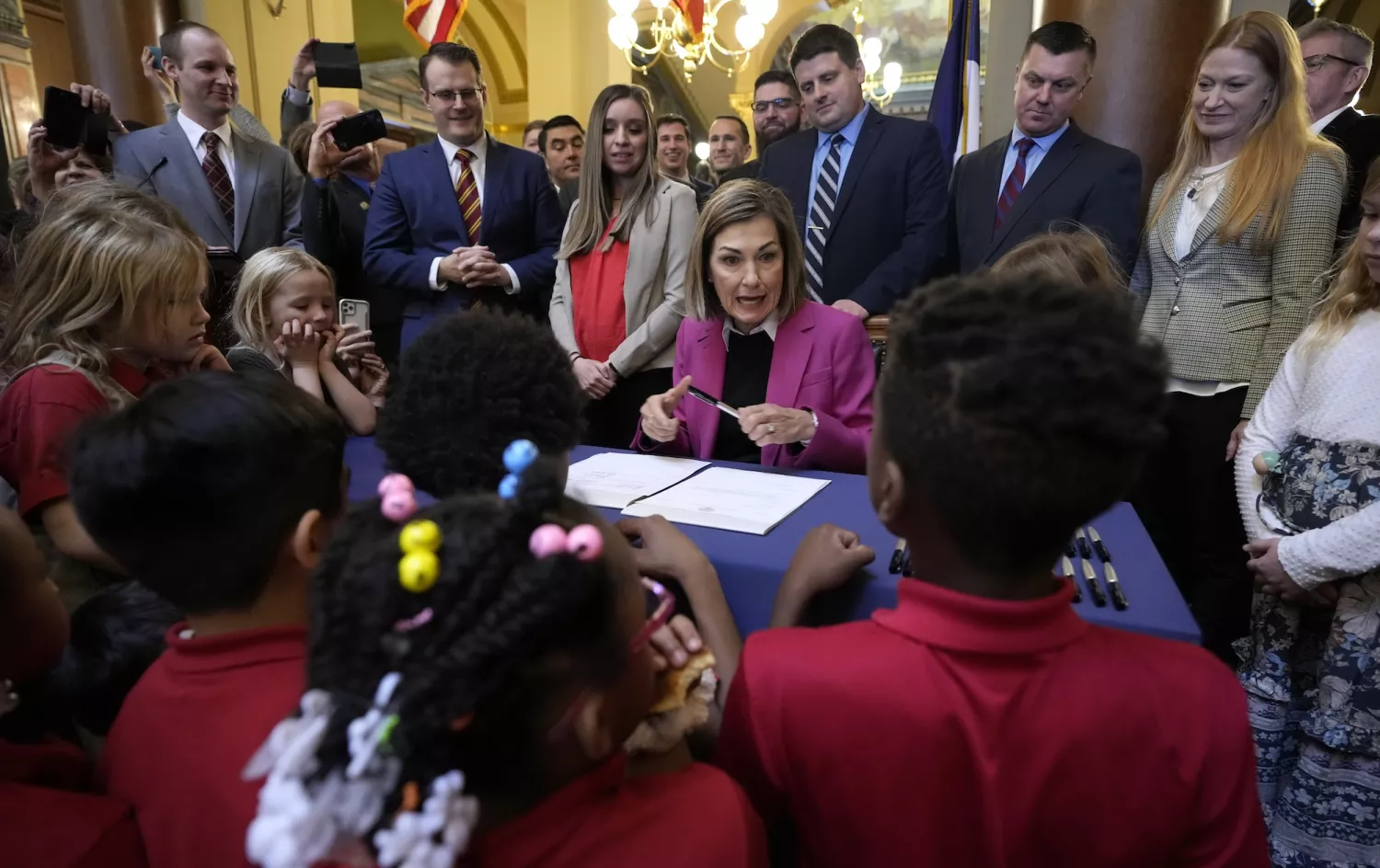

This disturbing trend can be seen in other states that have enacted sweeping voucher laws. When Ohio expanded access to its "EdChoice" voucher program in 2020, the percentage of participating students who were already enrolled in private school jumped from 7 percent in 2019 to 55 percent in 2023. And new data from the Iowa Department of Education reveal that two-thirds of students in that state who received a voucher were, again, already enrolled in private school, and only about 13% of recipients had ever previously attended a public school.

In addition, far from saving taxpayer dollars—a selling point from voucher proponents— Arizona’s general fund pays out more for ESAs than it does to pay for a public school education, according to research by the Joint Legislative Budget Committee (JLBC), the state legislature’s independent analysts. For example, the per pupil allocation is $900 less for high school public school students than for students whose education is funded through an ESA.

Overall, Arizona’s ESA voucher program is projected to cost $950 million next year, $320 million of which is unbudgeted.

The program, Gov. Katie Hobbs told Arizona lawmakers, “lacks accountability and will likely bankrupt the state.... It does not save taxpayers money, and it does not provide a better education for Arizona students.”

The damage won’t stop with public schools. Because ESA vouchers are funded from the state general fund, runaway spending on the program will inevitably jeopardize other services and programs.

“If other states want to follow Arizona, well—be prepared to cut everything that's in the state budget," Marisol Garcia warns. “Health care, housing, safe water, transportation. All of it.”

Vouchers Gain a Foothold

Even in the face of overwhelming evidence that these laws are damaging public schools and draining state budgets, many state legislatures were particularly receptive to vouchers in 2022 and 2023.

The school privatization agenda is supported by very deep pockets and recent rulings by the U.S. Supreme Court have paved the way for states to divert more public dollars to private religious schools.

“But if you ask, why more vouchers now, you also have to ask: Why attacks on LGBTQ students now? Why book bans now? It’s all part of the plan to destabilize public education,” explains Josh Cowen. “These lawmakers and their financial supporters don’t care about educational outcomes, and they don’t care that they blow through state budgets.”

In addition to Arizona’s universal expansion, seven states—Arkansas, Iowa, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah—passed new voucher programs, and 12 states expanded existing programs. Eleven states now have universal voucher laws, and more may be on the way in states such as Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee.

School privatization groups have also been quite successful at restructuring and rebranding vouchers to make them more attractive to many lawmakers and, to some extent, the public.

Most of these new laws are either in the form of ESAs or tuition tax credits. Tuition tax credits are designed to incentivize individuals and corporations to donate to non-profit organizations, which in turn bundle the funds and disburse them as private school vouchers. The donors receive a dollar-to-dollar tax credit in return.

These reconfigurations “represent an appealing end run around tough questions” around school vouchers, says Samuel E. Abrams, director of the National Center for the Study of Privatization in Education at Teachers College, Columbia University.

Still, despite the legislative successes, “it would be a mistake to think there is some massive, grassroots, public outcry for vouchers, because there isn’t,” adds Cowen.

And there is good news to report. In 2023, the Texas State Teachers Association helped keep enough lawmakers, nervous about vouchers’ impact on rural schools, on their side to repeatedly defeat Governor Greg Abbot’s universal voucher proposal. The Idaho Education Association led the way in defeating no less than seven voucher bills in the state legislature.

And Illinois recently became the first state to end its voucher program. In November 2023, lawmakers chose not to fund the tax-credit scholarship program, which was draining up to $75 million of state money.

“Public money belongs in public schools, and we are glad our lawmakers believe that, too,” said Illinois Education Association President Al Llorens. “Eighty percent of our public schools in Illinois are underfunded. We need to focus on providing the necessary funding to our public schools so that all children in Illinois continue to have access to a high-quality, public education.”

Elections Matter

“Where vouchers go from here probably comes down to the 2024 election,” says Josh Cowen. “And defunding public education is not a winning message. People still overwhelmingly support their public schools.”

In 2022, Arizona voters elected a pro-public education governor in Katie Hobbs, who has made rolling back the ESA voucher program —curtailing the runaway costs and demanding accountability measures—a top priority.

“The public expects that private schools, or anybody who is receiving this money, should be under the same regulations that public schools are,” says Marisol Garcia. “The polling is very clear on that. We will continue to educate the public, because I don’t think many families understand the potential impact these vouchers will have on public schools and their community.”

Even as the ESA voucher program’s abysmal record is exposed, educator activists in Arizona don’t expect too many of the law’s supporters to have second thoughts. Voucher supporters in the legislature have drawn a line in the sand: no cuts to the program.

“There’s so much national money behind vouchers, [and] these lawmakers are only responding to their donors. So the only way we will see real change is by electing a new legislature,” says Michael McGowan. “As a union, that’s what we have to focus on: help people understand what’s at stake and then flip some seats.”