Elementary school teacher Shayna Scott worked in New Jersey for 20 years, but she didn’t realize the power of the state’s collective bargaining rights—until she moved away. Her New Jersey local, the Irvington Education Association, had negotiated for better pay, safer workplace conditions, and more job security—successes that impacted Scott’s life, both personally and professionally.

But that changed when she became a teacher in Gwinnett County, Georgia, outside of Atlanta.

She soon learned that Georgia lawmakers have denied workers the right to collective bargaining—and the difference in her salary and working conditions was stark.

“The Gwinnett County Public School district has 30 steps,” Scott explains. “That means a new hire starting on step zero would have to work nearly three decades prior to earning maximum pay.”

According to NEA’s 2024 report on educator pay in the U.S., the average starting salary for teachers in New Jersey is the second highest in the nation. And the average salary overall for the state’s ESPs is the fourth highest in the country. By comparison, Georgia’s average starting salary for teachers is 39th in the nation; and the average ESP earnings are 36th.

And with no contract governing the daily duties of Georgia’s school employees, educators often do not have duty-free lunches or adequate planning time to collaborate with colleagues.

Still, Scott has seen how her union—and others across the country—are lifting educators’ voices and creating positive change, even without collective bargaining rights.

Who Can Bargain?

Collective bargaining laws vary greatly across the country. Some states guarantee bargaining rights while others “permit” bargaining, meaning that it is allowed only if the employer and the union agree to it, explains Dale Templeton, NEA’s Director of Collective Bargaining and Member Advocacy.

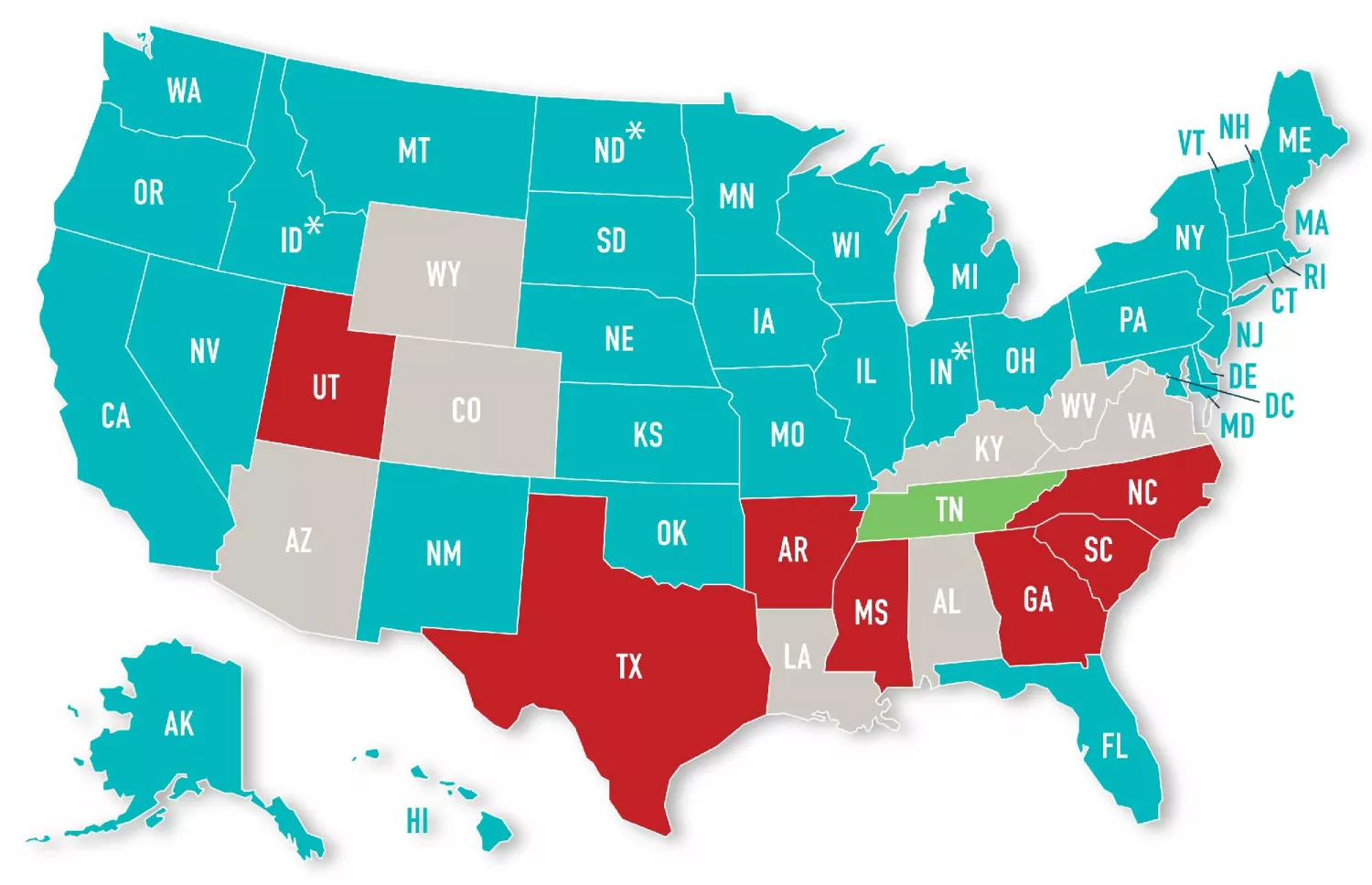

K–12 educators in 34 states, plus Washington, D.C., have a state law giving them the right to bargain collectively, and they are permitted to bargain in eight states. K–12 ESPs in 31 states and Washington, D.C., are guaranteed the right to bargain and are permitted to bargain in 11 states.

Templeton adds that states with collective bargaining pay educators higher salaries, increase student learning, improve educators’ working conditions, and attract and retain the highest-quality employees.

However, collective bargaining is illegal for public employees in Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Utah; for ESPs, it is also illegal in Tennessee. The remaining states permit bargaining at the discretion of individual school districts, Templeton notes.

“But if you live in a state without collective bargaining rights, you and your colleagues still have the power to advocate for better pay, benefits, and working conditions,” she says. “And Georgia is proof of that power.”

Georgia Educators Win Big

This year is a turning point for Georgia educators. Thanks in large part to advocacy by the Georgia Association of Educators (GAE), the state’s 2024 – 2025 budget includes boosts to educators’ salaries; more funding for pre-K and free and reduced lunches; and improved retirement benefits for bus drivers, cafeteria workers, custodians, and maintenance personnel.

“We use our voice to fight for our working conditions,” says Timothy Lyons, a language arts and life science teacher in Hephzibah, Ga. “We are consistently in contact with elected officials to address our concerns across the state.” GAE also regularly schedules meetings with district representatives and attends board meetings, Lyons adds.

Similar advocacy by GAE members in Atlanta led to an additional 11 percent salary increase for their district’s teachers—the largest ever earned by teachers in the district.

Another key strategy that paid off for Atlanta teachers? Electing a local educator to the school board who voted in their favor. But, according to Lyons, this increase is “not enough to compete with the ever-changing housing market in the Metro Atlanta area.”

Advocacy throughout the state must continue, Lyons says, because there are counties where the starting teacher salary is still low, and ESPs did not get a raise when the teachers did.

“[ESPs] do not make enough money to take care of basic living needs, so they are forced to work multiple jobs,” he adds. “Our ESPs spoke about needing a pay raise when certified employees received one. They are using their voice at meetings with politicians to have

this addressed.”

Tennessee Educators Gain Negotiating Power

Educators in Tennessee are also standing up for what they deserve. “[We] face unique challenges, including limited legal avenues for traditional collective bargaining,” says Neshellda Johnson, a professional learning coach at Hamilton K–8, in Shelby County, which includes Memphis and is the largest county in the state. “Despite this, we’ve found ways to stand together, raise awareness, and work toward change.”

Back in 2011, Tennessee lawmakers voted to outlaw collective bargaining and replace it with a process called “collaborative conferencing.” According to the Tennessee School Boards Association, collaborative conferencing allows representatives—designated by professional employees and the management team—to “confer, consult, discuss, and exchange information, opinions, and proposals on matters relating to terms and conditions of professional service, using the principles and techniques of interest-based collaborative problem-solving.” Collaborative conferencing is not collective bargaining, because agreements are non-binding, and local associations are not equal partners in it with the school district, Templeton explains.

In 2014, members of the Tennessee Education Association teamed up to form the United Education Association of Shelby County (UEA). Last year, UEA members voted to allow the association to negotiate with the school district through collaborative conferencing.

“[The vote] allows us to organize and collectively advocate for fair pay, adequate resources, and better working conditions,” Johnson says. “It’s also important to highlight that better working conditions for teachers directly benefit students. We hope the broader audience will recognize the connection between supporting educators and improving education as a whole.”

Another benefit to UEA’s efforts, Johnson adds, is that it helps gain respect and recognition for the education profession.

Five Ways to Create Change

Find out how your school community can create change, even without collective bargaining.

Sundjata Sekou (pronounced Sund-Jata Say-Coo) is a Hip-Hop loving, “dope”, Black, male, elementary school teacher in Irvington, N.J., and NEA’s 2024 writer-in-residence. You can follow him on Instagram @blackmaleteacher and email him at [email protected].