Key Takeaways

- Virginia lawmakers lifted a ban on collective bargaining by public employees in 2020; the law went into effect in 2021.

- About a half-dozen local unions already have their first contracts; most recently, Virginia’s largest, in Fairfax County, inked theirs.

- Collective bargaining guarantees them a voice in the terms and conditions of their employment. That means pay, benefits, and working conditions, like duty-free lunch or planning time.

[Editor's note: This story was updated on December 9.]

“Good morning, ladies! I’ve got really good news and doughnuts!” calls Loudoun Education Association (LEA) President Kris Countryman to a pair of bus drivers, walking through a depot lot on a recent morning.

The really good news? In early December, Loudoun educators had the opportunity to vote on whether they want LEA to sit down at the bargaining table with Loudoun County Public Schools administrators and negotiate a legally binding contract.

“It’s finally here,” Countryman tells a bus driver. “Saying yes means we can negotiate on your behalf for better wages, better working conditions, and better benefits."

And 'yes' is what they said. On Monday, December 9, LEA announced that the union had won overwhelming support from its two bargaining units, winning 91 percent of the vote among bus drivers, paraeducators and other "classified" staff and 96 percent of the vote among teachers, counselors, psychologists and other licensed staff.

With this, LEA is now the 10th Virginia Education Association (VEA) affiliate to become the exclusive bargaining representative for public school employees. Three other counties in Northern Virginia—Fairfax, Prince William, and Arlington—already have ratified their first contracts and won legally binding language around protected planning time, workload, bereavement leave, and more.

LEA hopes to begin bargaining in the coming months. Calling it a "significant win," Countryman says, "This will not only help us attract and retain quality teachers and support staff, but it will ultimately benefit our students and strengthen the school division.”

“I really should be a member.”

Dozens of Loudoun's union leaders worked together for years toward this election. But on a late November day, in advance of the election, Countryman is a one-woman road show, packing informational flyers, bags of red LEA t-shirts, stacks of union-branded caps, and dozens of glazed, frosted, and sugar-dusted doughnuts.

“Help yourself, there are chocolate-frosted back there,” she says, urging drivers to stop for a minute.

Countryman’s day started before dawn and would likely end around midnight. While parked outside a tiny, rural elementary school, eating a drive-thru chicken sandwich in her car, her husband would call and say, “How’s it going, honey? I haven’t seen you in a few days.”

Her first stop of the morning? One of the county’s school bus depots. Parking her own car strategically, in between lanes of school buses and drivers’ personal vehicles, Countryman catches drivers as they finish their morning routes.

Many who stop to chat hadn’t heard of the election—but are curious to know more. A constant topic? Pay. “A lot of drivers I know work two jobs,” one says.

“One job should be enough!” Countryman responds. Drivers also let slip that the district had suddenly stopped providing glass cleaner for their windshields. How are they supposed to clean with plain water?

Some are not LEA members. “You still get a vote,” Countryman assures them. Others proudly are, or considering it, now. “Union members will decide what we negotiate. If members say wages, then it’ll be wages,” she says.

“I really should be a member,” agrees a veteran driver. (Spoiler alert! By the end of the day, he would be!)

Around 10:30 a.m., when the stream of drivers trickles to a stop, she grabs a flyer and walks across the parking lot to a bus mechanic whose head is hidden by an upright engine hood. “Hi! I’m Kris, I’m your union president!” she calls.

"Spread the Word!"

Elapsed time: 0:00

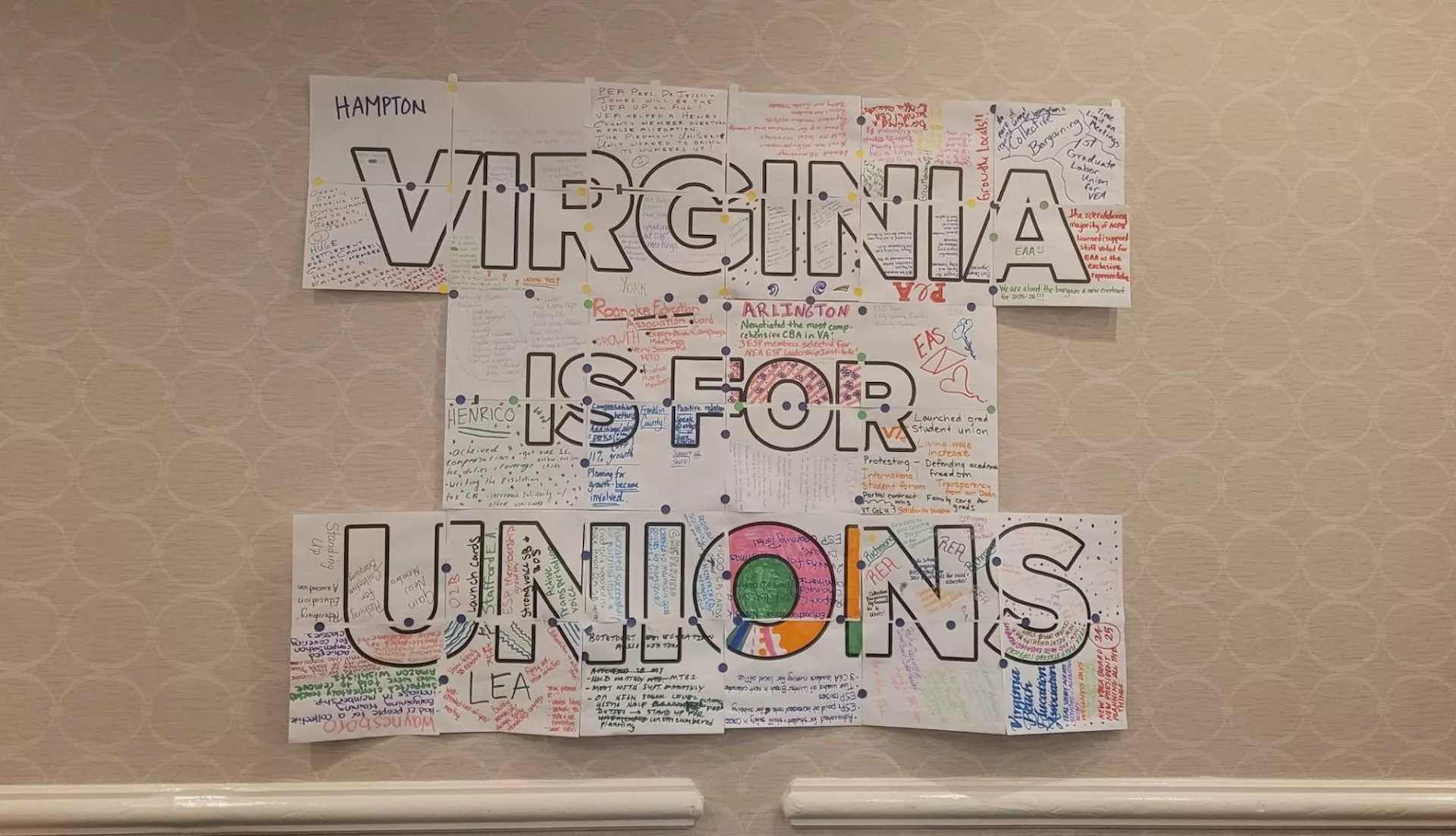

Total time: 0:00A Wave Across Virginia

In 2020, Virginia’s General Assembly lifted its nearly 50-year ban on collective bargaining by the state’s public employees, enabling educators to sit down and negotiate with school divisions. The new law, implemented in 2021, is complicated, but while VEA members work to improve it, they also are exercising their new rights across the state.

In May 2023, union members in the capital city of Richmond became the first in the state to ratify collective bargaining agreements, winning pay raises ranging from 5 to 38 percent, plus step raises. Protected planning time? Check. Limits on meetings? Check that, too. Richmond’s bargaining team also won 3 days of paid personal leave and access to healthcare benefits for food-service workers. In all, they inked four contracts for various bargaining units.

The Montgomery County Education Association, in southwest Virginia, followed with a first contract that went into effect in January. Among its provisions? Duty-free lunch and more control over lesson plans, caseload limits for special-education teachers, and a guaranteed 85 minutes of planning time a day for elementary teachers (and 80 for middle and high school).

Meanwhile, the Northern Virginia unions began inking contracts in 2023, beginning with Prince William County, followed by Falls Church and Arlington County.

“When we embarked on this journey, we knew it would not be easy,” said Arlington Education Association (AEA) President June Prakash, at the June school board meeting where AEA’s two contracts were approved. “We faced resistance, skepticism and numerous challenges. Yet we remain steadfast driven by the belief that every worker deserves a voice, a seat at the table, and the power to shape their working conditions.”

Fairfax Wins!

Most recently, the Alliance of Fairfax Education Unions, representing educators in the biggest school district in Virginia and 11th biggest in the U.S., ratified its groundbreaking contracts on November 25.

Its two contracts—one for teachers, counselors, librarians, school psychologists, and other certified educators, and the other for instructional and public health assistants, custodian and transportation staff, cafeteria workers, and other "operational" staff— include pay raises of roughly 7 percent this year, followed by average 5.5 percent raises, including step increases, in years 2 and 3.

But the thing that Fairfax Education Association Leslie Houston is most proud of? It’s the new “just cause” protections for discipline and dismissal, which will go a long way to protecting educators from capricious administrators.

“There’s still this ‘good old boy’ system here that folks are trying to change. In that system, you’ll find some principals—not all, I want to make sure we understand it’s not all—but some who feel like it’s their school and all the things are their way,” says Houston. “Just cause will make sure disciplinary actions are based on legitimate reasons that are clearly articulated. The process has to be fair.”

The 27,500 educators represented by these contracts also have the right to union representation in disciplinary meetings now. They have bereavement leave. Support staff have six additional paid holidays. And teachers finally have an answer to the perennial problem of no planning time: The new contract ensures elementary teachers’ 300 minutes of planning time per week can’t be gobbled up for meetings. And it guarantees at least 30-minute increments.

“Ninety-eight percent voted to pass the [tentative agreement]. That’s incredible,” says Houston. “After all of this done, I’ll go and look back and say, ‘wow, did this really happen? This is really what happened.’”

And what it shows the rest of the Virginia? Or even the whole nation? “What this shows is it can be done,” she said. “But people have to be persistent. You have to drown out the white noise and focus. You have to believe.”

“I’m voting yes…”

In Loudoun, Countryman pulls out of the bus depot around 11 a.m. and heads to LEA’s office where she meets with union staff, talked about email lists and get-out-the-vote efforts, and jotted notes in the margins of her crowded day planner.

A tiny charter school in the far reaches of western Loudoun County sent her an invitation to visit. Can she fit it in? Of course she can.

Back in her car, she first makes a quick stop to meet with a building rep at the small alternative high school in Leesburg, Loudoun’s biggest town. He needs more flyers about the election to share with his colleagues.

From there, Countryman steers toward the tiny burgs of western Loudoun. This isn’t what people likely envision when they think about Northern Virginia’s suburbs; it’s narrow roads that twist between expansive green fields, past tiny stone churches and elementary schools with 100 or so students. Countryman checks her GPS, over and again.

She visits two more schools and meets with dozens more members and potential members. A custodian rolling his cart down an empty hallway—students are long gone—says, “I’m not a member… but I’m voting yes.”

One teacher tells her, “I love working here. I love working in Loudoun County. But I do not trust the school board. I don’t think they care about educators, or even students sometimes.”

She is also voting yes.

United We Bargain, Divided We Beg

The sun is low when Countryman pulls into Loudoun County High School for an LEA town hall. On the agenda: Identifying issues that union members want to tackle in their first contract.

When you live in a state where politicians explicitly prohibit public employees from collective bargaining—like Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas—educators can still be active and effective advocates. Union members rally at statehouses, speak up at city and school board meetings, and leverage community power. They ask, demand, beg, and shame their lawmakers to do what’s right.

Bargaining, on the other hand, guarantees educators a seat at the table and a voice in the terms and conditions of their employment. (Check out NEA’s 2022 white paper on the benefits of bargaining!)

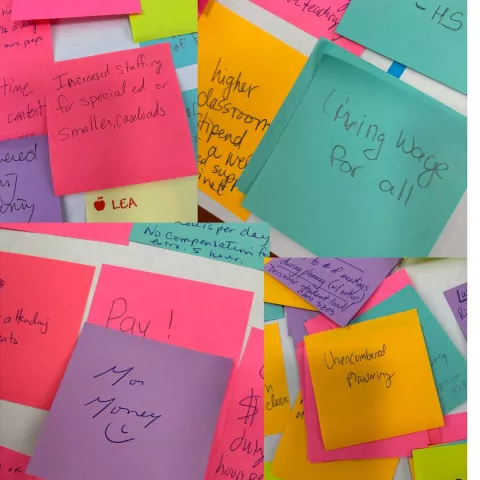

In Loudoun, union members can bargain in three areas: working conditions, wages, and benefits. That could mean more planning time. Workload caps. Bonus pay for coaches and club advisors. Fewer meetings. On-call pay for substitute drivers. Maybe even more affordable housing.

“What are you willing to fight for? What is going to make an immediate impact?” VEA organizer Jeremiah Hoyt asks the 40 or so LEA members assembled in the high school’s library.

“Protected planning time,” murmurs one teacher. “More pay,” writes down another on a stack of Post-its.

Countryman displays her own employee contract with Loudoun County Public Schools. It’s a page and a half. By comparison, the new collective bargaining agreement in Prince William County is 53 pages. Arlington’s is 81. For an hour, LEA members pore over the new Virginia contracts, taking notes.

Excitement grows.