Imagine standing up in a staff meeting at school and saying, “Let’s address institutional racism in our schools.” How would your colleagues react? Some might welcome an open discussion, but many would probably shift in their seats and glance around nervously. A few might even get up and walk out of the room.

Talking about race openly and honestly is essential to creating educational equity for all students and members of the school community. But the approach to the conversation must be handled with care.

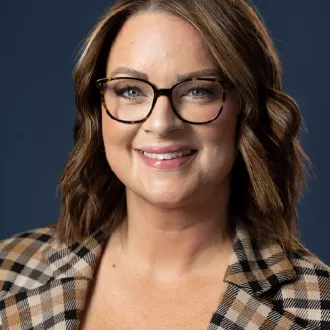

“You can’t march into a room of educators and announce that you are going to talk to them about racism. People will bristle and back away immediately,” says Caitlin Pankau, an Idaho English teacher, facilitator for NEA’s Leaders for Just Schools (LJS) program, and staffer with the Idaho Education Association (IEA). “You need to take the right steps first, and that’s what Leaders for Just Schools is all about.”

The program helps participants better understand how they can cultivate equitable, just schools for students of every race, place, background, and ability.

LJS focuses on the intersection of racial justice in education and understanding how to use the levers of local, state, and federal policy—specifically the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)—to create equitable learning spaces for all students.

Everyone Can Be a Leader

More than 200 educators from across the country are currently engaged in the three-year program. Typically held in summer, the training kicks off with virtual sessions followed by in-person learning experiences.

In the first year, educators learn about critical definitions and topics in education justice. And they turn inward to explore their own biases.

In year two, participants examine structural inequities in education and focus on building partnerships with families and communities to break those structures.

In year three, they create a plan to address a “problem of equity” that they have identified in their own schools or communities. Over the course of this learning journey, educators develop the knowledge and skills to advocate and organize for education justice.

A powerful preliminary step is to ask participants to reflect on their race and how it has impacted their experience.

“The goal is not to send White people down a shame path,” Pankau says. “It’s to help them identify and acknowledge advantages and disadvantages people of different races experience.”

Quote byCaitlin Pankau , English teacher, Idaho

Tapping into educators' talents

Pankau has completed all three years of the program and is now an LJS facilitator. She and two Idaho colleagues—high school science teacher Jamie Morton and middle school English teacher Lindsey Smith—were part of the pilot cohort in 2018 and engaged in the program as both participants and facilitators.

“We were so proud of where the curriculum had taken us, we wanted to take it more broadly at home,” says Smith, who worked alongside Pankau, Morton, and IEA to design a statewide LJS curriculum.

Today, the colleagues are fostering a community of educator-leaders who are prepared to address institutional inequities in their schools

and communities.

“The work, quite honestly, will never be done, but we are showing educators across the state how to advocate for equity for our students by using policies like the Every Student Succeeds Act to promote the schools we want.”

The LJS curriculum offers a structured journey for educators who are passionate about these critical issues.

“The first step is figuring out how we can change as individuals,” Smith says. “Then we learn how to talk about race and inequities, which are not always easy to discuss. Then, when we’re more comfortable talking about this openly, we look at the students and how they are impacted by what we teach and by other factors at school, like dress codes or discipline practices.”

That’s when it all comes together, say the three educator-leaders. They note that it’s powerful to discover how everyone can help make schools equitable by first taking a hard look inward at how one thinks, speaks, and acts, and how that is received by the world.

“Once you know better, you do better,” Pankau says.

So how have LJS participants been doing better?

They have the opportunity to create an advocacy plan addressing an issue in their school, district, or state. From implementing new classroom policies to reviewing school handbooks to offering testimony at school board meetings, an array of projects stem from members’ engagement in the program.

Quote byLindsey Smith , English teacher, Idaho

‘We're Continuing the Work Back Home’

The beauty of the program is that the work is ongoing, Morton says.

“Having one- or two-day trainings on equity wasn’t working, but with LJS, the goal is to make ongoing, systemic changes with a cohort of people who connect with each other like we did, and then make connections back home,” she shares. “We keep working on this, purposefully and intentionally, throughout Idaho. We may be graduates of the national program, but we’re continuing the work

back home.”

Now there are about 30 educators who are incorporating the LJS curriculum into learning experiences throughout the state. They hold sessions at state and regional IEA meetings and offer them through their districts and schools.

After the training, facilitators check in regularly on the educators’ progress: Are they making changes to lessons and updating curricula to make learning more equitable, inclusive, and culturally sustaining? Are they addressing unfair school policies? Are they participating in committees at the school, district, or state level to ensure equity is on the agenda? Facilitators find out where people need assistance and how they can help.

“Our hope is that folks will keep practicing what they’ve learned, either in groups or on their own,” Pankau says.

“If you’re not a facilitator by nature, then your role can be to simply change your awareness, which then impacts your classes and potentially the lives of thirty or more students,” she explains. “Then, if you have a conversation with a colleague or two, and they change their awareness, that impact grows.”

The training covers topics such as defining equity, understanding “-isms,” and examining the consequences of segregation on public education.

“The program does an excellent job of explaining White privilege. Two things can be true at the same time. White people may have worked hard for things they have in their lives, but they have White privilege all the same,” Smith notes. “I was not held back because of systemic racism or the color of my skin. It starts with acknowledging our own privilege as well as being more mindful of the way that policies can impact folks differently. The Leaders for Just Schools program allows White people to see themselves in this work. We learn how to become accomplices in uprooting systemic inequities without centering ourselves.”

Awareness generates empathy and grace. It also filters into lesson plans—such as including literature in which People of Color are the protagonists and heroes, or examples of leaders of color in the arts, science, or engineering. Awareness can help interactions with colleagues, too.

All of this work takes time, practice, and relationship building, Pankau says, but the effort pays off by creating more equity, more successful students, and better humans.

Quote byJamie Morton , Science teacher, Idaho