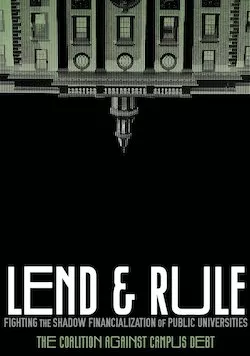

In a new book, “Lend & Rule: Fighting the Shadow Financialization of Public Universities,” the Coalition Against Campus Debt dives into the kind of campus debt that nobody talks about.

As state funding for public colleges and universities has declined, the amount that these institutions borrow to pay for new buildings, etc., has soared. Today, campus debt drives faculty and staff layoffs, academic program closures, and increases in student tuition. (Student debt, too!) It’s a primary reason why faculty and staff are working so hard, for so little pay.

The authors, who include Massachusetts Teachers Association members Joanna Gonsalves, Barbara Madeloni, and Rich Levy, explain how faculty, staff, and students can uncover debt on their campuses, reveal it to students and community members, and organize for a better vision for public higher education. The book functions like a handbook with useful appendixes of worksheets.

"Too much of this has been obscured and made difficult as a way of maintaining power," notes Madeloni. "By making this a handbook, rank-and-file union members can come to understand how this works on their campuses—and be confident about using their voices... Ultimately what we need to demand is fully-funded public higher ed."

Recently, Madeloni, Gonsalves and Levy sat down with NEA Today.

[Interested in purchasing "Lend & Rule"? NEA members will receive at 15% discount when they use the code LEND&RULE at Common Notions publishing.]

A lot of people don’t know what you’re talking about when you say campus debt. Their minds automatically go to student debt. How to do you explain or talk about it?

Rich Levy: My one-sentence summary is basically that because of state cutbacks to higher ed, campuses are forced to pay for capital construction and deferred maintenance, and then the cost of that debt is passed on to students through tuition and fees and to faculty and staff in terms of cutbacks.

Barbara Madeloni: And after that sentence, I say, ‘these colleges, universities, institutions are now carrying all this debt—and they pay debt servicing fees before they can address their operating costs. Who’s paying those debt servicing fees, except for students? And how are they paying those debt servicing fees? By taking out loans from the same banks!’ When people hear that, and I give them the numbers on what that means for individual students carrying that burden, it blows people’s minds. They’re interested in finding more.

The book makes clear that colleges and universities began borrowing when state lawmakers began cutting support, and it shows how that started during the Reagan-era when the notion of the “public good” also began declining. What’s also interesting is how colleges and universities were finally becoming more racially integrated at that same time. Can we talk about how race is a factor?

Madeloni: If you look at what happened with the California State University system and City University of New York in the 60s and 70s, [you’ll see how and when] politicians got afraid. Black and white working-class students were educating themselves and building a movement. So, they were terrified—and needed to shut down this point of access. It was about racism certainly.

Levy: Racism also comes out in the tail end, as students of color also have considerably more student loan debt, have a harder time paying it off, have a higher default rate—and up to a third of their student loan debt is campus debt. Campus debt is built into student loan debt. Essentially students are paying twice for it.

What do you recommend as the first step for faculty and staff interested in this issue?

Levy: The first step is raising awareness that institutional debt exists—because most people don’t know and it’s virtually invisible. The next step is figuring out what your campus debt is. The book [and website] include a worksheet that will take about an hour and a half. You can figure out what percentage of the budget is debt service, and then figure out how much each student pays per year. You can also start imagining what else that money could pay for—how many faculty, what kinds of student programs.

Joanna Gonsalves: This allows workers to start asking questions!

Why Write This Book? And Why Read It?

Elapsed time: 0:00

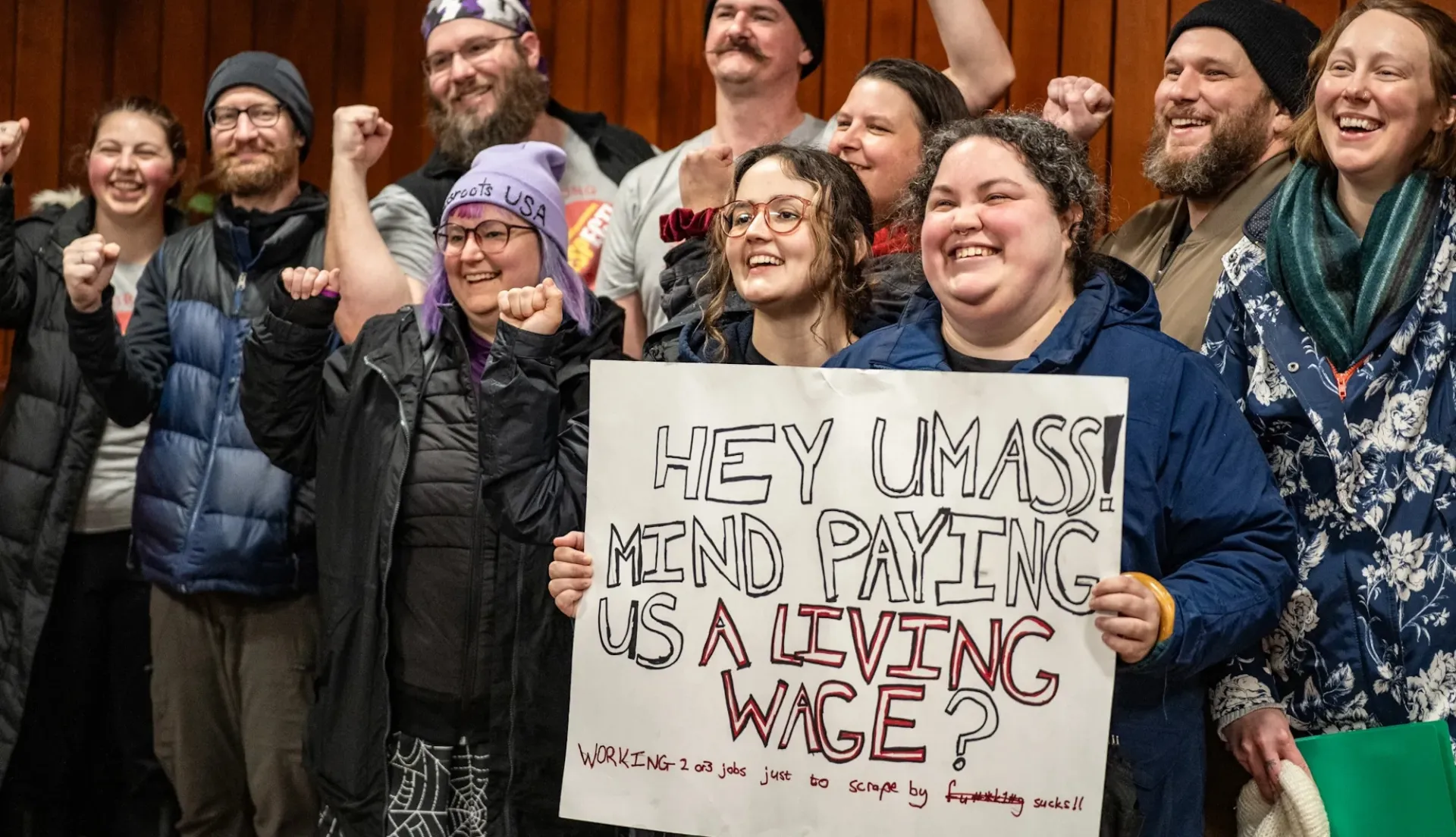

Total time: 0:00At Salem State University (SSU), the issue of campus debt emerged in spring 2020, when college administrators announced suddenly that they planned to lay off 25 percent of adjunct faculty and furlough everybody for five weeks. A small group of union members dug into the numbers and found that institutional debt was driving the budget crisis. Ten percent of SSU's budget—$2,690 from every student every year—went to pay back SSU's construction loans. When tuition payments dipped during the pandemic, SSU's loan agreements forbid them from going into reserves to make debt payments. You all led an incredible effort to make the community aware. How do you reflect on that time now and tell that story?

Gonsalves: We talk about it all the time, but interestingly what we’ve been focusing on lately is how the crisis—the discovery of how debt was ruling our institution—has actually helped radicalize our campus a little bit more. It certainly got our union more involved. Our focus is using this in a way to strengthen us—not to just depress us. How do we, as workers, do something? The book provides the framework and analysis of what needs to be done and why.

Levy: Two other parts of the Salem State experience: One, it provided a material basis to align with students—because they’re the ones who get it. That increased our collective power a lot. One of the phrases in the book is ‘administrations do not respect students, but they disrespect them less than they disrespect faculty.’ When we would ask to talk to the president’s executive committee, we’d get ‘uhhhh.’ But when we said we had four students coming too, we’d get an audience. That also empowered the students. Four thousand of them—on their own—signed a petition against the furloughs and its linkage to campus debt.

The second thing: Salem State is now super sensitive to taking out debt. We have a new giant construction project and amid ongoing discussions of how we’re going to fund it, they’re saying, ‘We’re not going to take out more debt! We’re not going to take our more debt!’

Something That Might Surprise You About the Organizing Work at SSU

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00What are some of the challenges to this work?

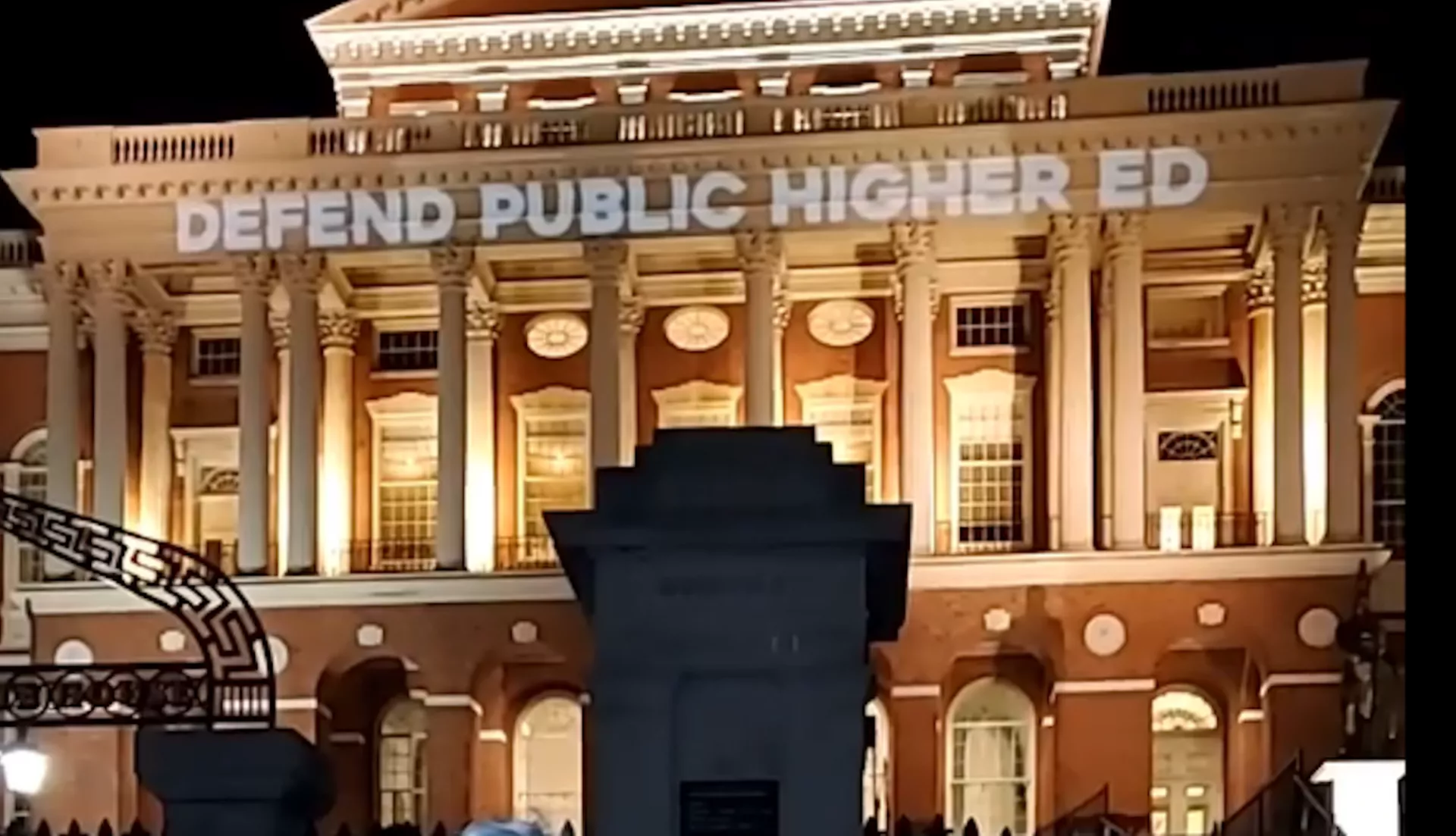

Madeloni: Ultimately what we need to demand is fully funded higher education, which doesn’t include taking on this kind of debt. It can feel like we’re walking toward a horizon that is very far away, but we are building power and getting some wins along the way. Look at what happened with the millionaires tax in Massachusetts: We won.

Levy: Because of austerity, people have increased workloads and a lot of the faculty are teaching adjunct jobs as well, just to get by. So, when we try to do rank-and-file organizing, one of the responses is that ‘this really makes sense, I just don’t have any time. I can’t possibly take on more thing.’ It’s really imperative to break that spiral by finding and creating small victories that increase confidence and encourage people to take the next step. The other thing is that fear of retribution by the university can be serious. People are justly afraid of that.

But as sophisticated as university administrators can be, they can do incredibly stupid things — and never miss the opportunity to use those. At Salem State, they published that each student pays $2,960 per year, just for campus debt, because they thought it would inspire lenders. They never thought we’d read it. When we started using it, they yelled at us!

What’s next for you all?

Gonsalves: Rich and I are part of a project that is looking at all the other corporations on our campus. Once you start looking at the budget, and where the money is going, you start to see it’s not just the banks and their capital lending projects. We’re looking at all the other corporations on our campuses, taking away union jobs and sucking the money right out of our campus. They’re part of the reason tuition and fees are so high. It’s not just campus debt. It’s the financialization, the corporatization of higher ed… Our campuses are nothing more than a marketplace where there can be profits for corporations.

Madeloni: When you look at the title of the book, “Lend and Rule,” it’s about who is making decisions on our campus—and it leads to questions: what should be happening instead? Debt has been naturalized. A business mentality of what is the purpose of higher education has come to dominate. When we pull back the curtain and then ask ourselves, ‘What are we here for?’ the conversations [that ensue] are part of what will carry us forward in the struggle. We have a vision of what we want—and it’s fully funded public higher education.

What Makes Barbara Madeloni Hopeful? Listen here.

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Register for the Webinar

How did it get this way? How do we organize to free public higher education from the talons of debt and create a space for liberatory education? Join the Coalition Against Campus Debt for a free webinar at 8 pm ET, October 29, as they share insights to these questions from their book, Lend and Rule: Fighting the Shadow Financialization of Public Higher Education.