Key Takeaways

- The Brown v. Board of Education decision ended legal segregation in public schools overnight; it also ignited mass resistance that continues today through policies that drive segregation and racial inequities.

- The promise of Brown has always existed, and so the work of educators, unions, and allies continues to help achieve integration and equitable outcomes for all students.

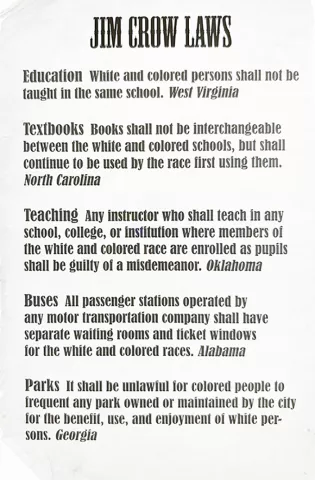

This year marks the 70th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, a landmark Supreme Court decision that ended the legalization of racial segregation in public schools. The decision, issued on May 17, 1954, also shattered Jim Crow laws and served as the cornerstone of the civil rights movements.

Since then, it’s been a seesaw of social progress and setbacks to fulfill the promise of Brown: Integrated and equitable schools for all students.

White resistance by certain elected officials, community members, and families has long plagued the ruling, and renewed efforts are on the rise. Extreme conservative groups purposefully mischaracterize students—whether they’re Black, brown, or white; Native or newcomer; Asian; LGBTQ+; or differently abled—and stoke fears about what's being taught in schools, from kindergarten through college.

These dog-whistle strategies are being used to dictate what teachers and faculty can and can't say, to ban books, and to block students from learning shared stories of confronting injustice.

While the road to racial and educational equity may be long, the collective vision of Brown can be achieved.

Brown Showed Potential Early On

The implementation of Brown v. Board (known as Brown II) was slow going given that the court left it up to Southern states to end segregation with “all deliberate speed.” This essentially translated to no speed at all.

It would take more than a decade for school officials to desegregate schools.

However, “it did move the ball forward,” says Derek W. Black, a professor of law at the University of South Carolina School of Law, where his work focuses on educational equality and opportunity, civil rights, and constitutional law.

“There was tremendous amount of progress made between the late sixties and the end of seventies,” he says, explaining that post-decision the number of Black students enrolled in desegregated schools in the South went from less than 1 percent to 40 percent.

“When you think about effective education policy and social change, there's nothing that gets close to [Brown v. Board], achievement gaps closed more during that time than any other period in history,” he says.

According to a 2001 analysis by the National Center for Education Statistics, throughout the 1970s and early 80s, academic achievement and high school completion rates among Black students climbed substantially, and the gap between them and white students narrowed sharply.

By the 1990s, progress stalled and achievement gaps in every grade and subject widened. And today, schools are more segregated then in the late 1960s.

What happened?

“It's not that Brown failed,” says Black. “It's that we failed to finish the job.”

And by “we,” he means federal officials who withdrew their support from school desegregation efforts.

In a 2022 article, Janel George, an associate professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center and the founding director of the Racial Equity in Education Law and Policy Clinic, spells out this departure:

“President Nixon nominated Supreme Court justices who pushed back on school desegregation remedies. President Reagan eliminated the Emergency School Aid Act, which provided federal funding to school districts committed to desegregation. He eventually eliminated most federal funding for school diversity, leaving only the Magnet Schools Assistance Program intact, and undermining progress on diversity,” she said.

And the tactics of the past are being used today to preserve segregation and racial inequality.

The New Massive Resistance

Today’s resistance resembles much of the past practices post-Brown.

In an upcoming paper out of the Georgetown Law Journal, George frames the new resistance as deny, defund, divert, and argues that “the same tactics lawmakers employed during massive resistance underlie [today’s] anti-CRT efforts as well," and explains that “a lot of white supremacists use the same tactics over and over because they've proven effective,” she says.

Critical race theory has been used by the likes of conservative activist Chris Rufo who, in 2021, tweeted, “We have successfully frozen their brand—‘critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perception. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all the various cultural insanities under the brand category.”

According to George, here’s how the new resistance compares:

The Road to Progress

Undoing policies that drive segregation is a good start toward integration and racial equity, and progress has been made.

When discriminatory policies like red lining and restrictive covenants laws, for example, confined Black families to segregated neighborhoods, this reflected in school buildings across the country.

Transportation, such as bussing, would be critical toward desegregation efforts. However, anti-bussing backlash from the 1970s caused Congress, at the time, to bar the use of federal funds for transportation to support school integration. The law remained in place for nearly 50 years—until 2021, when the Consolidated Appropriations Act was passed and included language that eliminated the prohibition.

“For people who want to maintain segregation … it's more politically palatable to say, ‘I'm opposed to bussing’ than to say, ‘I'm opposed to integration,’” says George.

Today, this happens with vouchers, created by politicians who saw them as a way to override laws that guarantee every student, whether Black, brown, or white, has the freedom to learn and thrive. Vouchers have perpetuated segregation, too.

“We saw vouchers, in the late sixties and early seventies, as a way … to allow white parents to avoid desegregated schools,” says Black. “Now they are using them to avoid public education altogether.”

And vouchers pose a real threat to the existence of public education.

“If vouchers end up allowing some large number of middle-income families to leave the public school system … what we have left is a public school system in which only poor kids and kids of color go,” he says. If this were to happen, then “the public education project as we have known it for the last two centuries is over. Full stop.”

Voucher Schemes Blocked Nationwide

That’s why NEA continues to beat back voucher schemes across the country so that tax dollars go to schools that are accountable to the public. Here are some of the latest victories:

-

Ruled unconstitutional, NEA Alaska won its court case against the state to stop parents of children enrolled in homeschool programs from using public money to buy curriculum materials and pay other costs related to their children’s coursework, including private and religious school tuition.

-

In Tennessee, a voucher program failed in the state legislature, after the Tennessee Education Association loudly opposed it.

-

The Texas State Teachers Association helped keep enough lawmakers on their side to repeatedly defeat Governor Greg Abbot’s universal voucher proposal.

-

The Idaho Education Association led the way in defeating no less than seven voucher bills in the state legislature.

-

And Illinois recently became the first state to end its voucher program, which was draining up to $75 million of public money.

Gloria Register Jeter, a North Carolina high school student in the 1960s, recounts her experience with desegregation.

Elapsed time: 0:00

Total time: 0:00Where Do We Go from Here?

For the team of attorneys who litigated on behalf of Brown, they envisioned a more all-inclusive approach to integration. Instead of firing Black educators or demoting them to another position, they would teach in classrooms with white and Black students.

“Their vision … included the presence of Black teachers who would provide that kind of nurturing and support for Black students. Instead, the burden was placed on Black children to go to majority white schools that were violent, hostile environments,” says George.

Nonetheless, the decision was still a powerful ruling.

“We had to, as a country, decry Jim Crow,” she says.

And so, the work of educators, unions, and allies continues to help rebuild the Black educator pipeline through programs such as Grow Your Own and Call Me Mister; fully fund public schools so that every student, of every race and place, has a high-quality education that prepares them for their future; and attract and retain more educators through competitive pay; and end exclusionary policies that push out Black students from schools, among many more successful efforts.