Key Takeaways

- Students of all ages and backgrounds are experiencing unprecedented levels of sadness and hopelessness.

- In rural communities, however, mental health challenges tend to be more severe, compounded by lack of access to services.

- With the crisis growing, educators in rural districts have been mobilizing to bring more resources to their schools.

A Plea From the Community

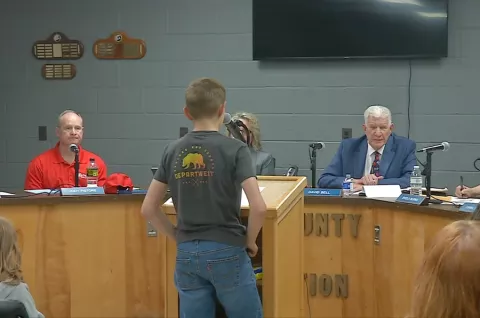

When educators, parents, and students filed into the town hall center in Hamlin, W.Va., one day in April, they were determined and hopeful that they would change minds. The school board had recently announced plans to lay off the 10 social workers employed by Lincoln County public schools. The county, everyone was told, simply could not afford them.

Putting a price on children’s mental health seemed abhorrent. One by one, community members stood at the microphone and implored board members to find the money. The social workers were saving lives, and the students could not imagine facing the upcoming school year without them. Hamlin is the county seat and has a population of 1,040. Much of the county is marred by poverty, crime, and opioid addiction.

“The social workers speak to our kids every day,” says Catricia Martin of the West Virginia Education Association (WVEA). “They are an integral part of this community.”

Ten-year-old Grace told the board how her social worker helped her through post-traumatic stress disorder after a recent car accident. “If they take away these social workers, … people with depression and suicidal thoughts … suicide will increase,” she told a local TV reporter after the meeting, as she fought back tears. “It’s not OK!”

The school board listened impassively and expressed concern but said their hands were tied. The grant that paid for the positions had expired, and there were no available funds in the general budget. Anyway, there were other priorities—including the possibility of a new school sports complex. The county could keep one social worker. The other nine would have to go.

The school board’s decision was heartbreaking and gut-wrenching, says Cassie Stone, vice principal of Duval PK-8 school, in Hamlin.

“It felt like a slap in the face. The trauma our students are facing is very real. They can’t focus on learning. If we don’t give them the help and resources they need, many are not going to make it.”

Record Levels of Sadness and Anxiety

The surging mental health crisis facing young people has been on the nation’s radar since the pandemic. This heightened awareness, however, didn’t make the results from a recent survey any less shocking.

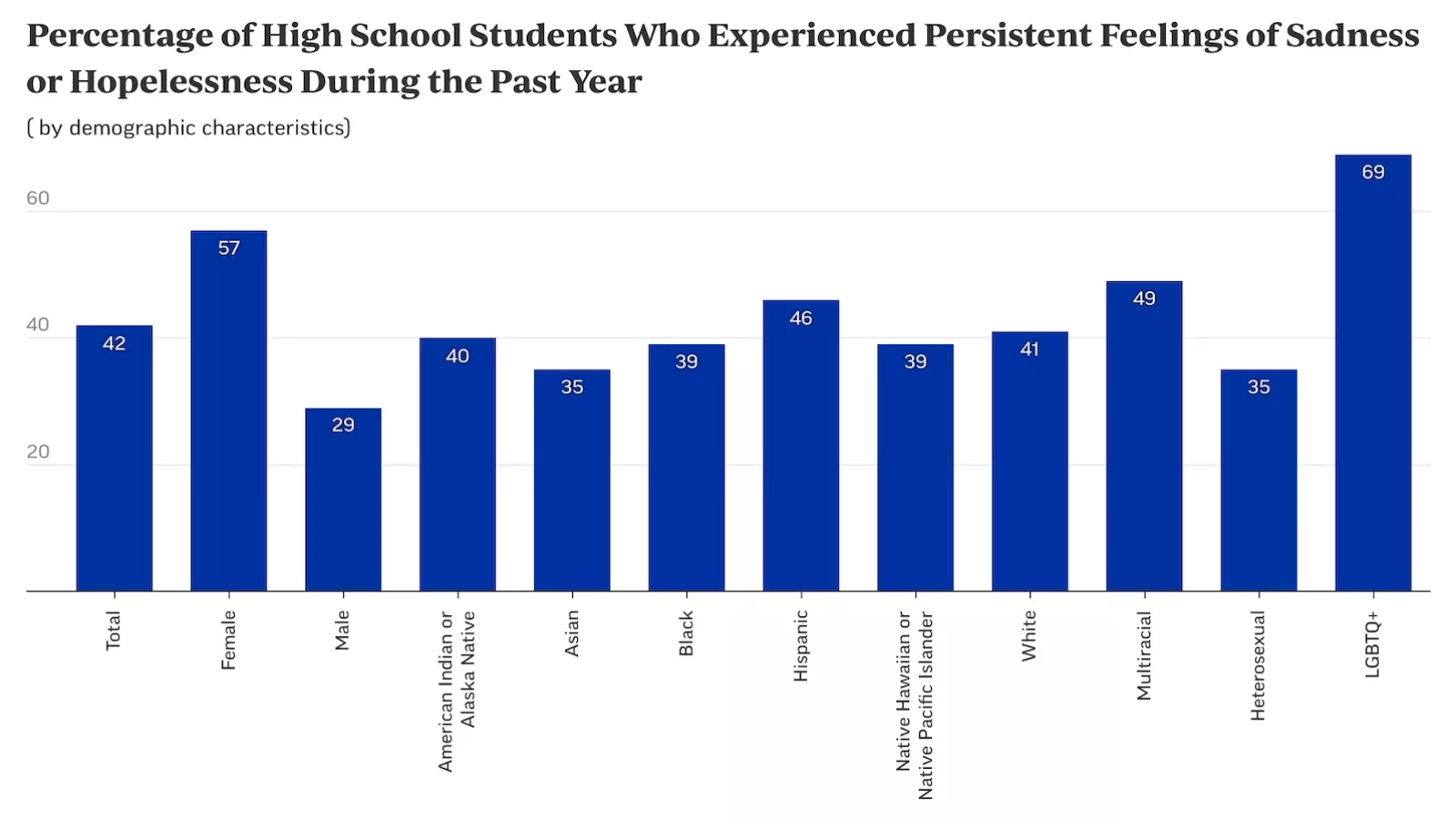

In March 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that 42 percent of high school students were suffering from overwhelming stress and anxiety—a 50 percent increase from 2011. But the data on girls was especially alarming. Nearly 3 in 5 girls felt persistently “sad or hopeless”—double that of boys. That figure represents a nearly 60 percent increase from 2011 and the highest level reported over the past decade. Nearly 1 in 3 seriously considered attempting suicide—up nearly 60 percent from a decade ago. Among LGBTQ+ youth, the trends were even more alarming.

Students of all ages and backgrounds are experiencing these heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and trauma. But young people in rural communities are facing graver challenges. Serious mental illness, adolescent depression, psychological distress, and suicide are higher in rural areas than in urban areas.

Mental health services, however, are limited in rural communities, and a lack of public transportation makes it difficult for many to seek help far away. Although more widely available, tele-health remains an imperfect solution.

Rural schools are also disproportionately affected by staff shortages. Recruiting and retaining counselors, psychologists, and social workers in remote areas is a perennial challenge. Caseloads can be overwhelming, leading to staff burnout and higher turnover rates.

And then there is the stigma.

“There are those ‘old school values’ in our town that prevent people from seeing the benefit of mental health treatment. It’s still taboo,” says Athena Robinson, who teaches social studies to middle schoolers in California City, located in the Mojave Desert.

Factor in high levels of substance abuse and the widespread availability of firearms, and it’s “a perfect storm scenario,” says Catherine Bradshaw, associate dean at the University of Virginia (UVA) and co-director of the National Center for Rural School Mental Health.

The influx of federal funds from the Biden Administration’s American Rescue Plan (ARP) and the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act—both championed by NEA—have boosted many schools’ abilities to support student mental health and social and emotional learning.

But school leaders and educators, especially in many rural communities, continue to struggle with dwindling resources and a stubborn lack of attention to the severity of the crisis. “We needed more preventative interventions prior to the pandemic, and now we have more stress on the system than ever before,” Bradshaw says.

The Burden on School Counselors

In many rural communities, a school counselor or psychologist may spend hours in the car each day, traveling long distances to visit multiple districts.

Haley Kunze and Brandy Rose, who are psychologists for Nebraska’s Educational Service Unit 7 (ESU 7), do just that. ESU 7 is 1 of 19 education subdivisions in the state and serves 13,000 students in 19 school districts across 7 counties.

Kunze, Rose, and their colleagues fan out each day, sometimes driving an hour from their respective homes to their first school visits.

“I usually drive somewhere between 1,000 to 1,200 miles every month,” Rose says. “You get used to it, but it can be exhausting.”

Quote byBrandy Rose, School Psychologist, Nebraska

Prior to the pandemic, the psychologists’ school visits usually entailed check-ins with special education teachers as well as testing and evaluations. Since 2020, however, they have fielded more requests from teachers to meet one-on-one with students who need help with social skills and emotional regulation.

“My workload in that area has doubled over the past few years,” Kunze says.

But time and resources are limited. And the counselors in ESU 7—and across the nation—are stretched thin. The three pillars of school counselors’ work are academic development, career development, and social and emotional development. They are not therapists, says Jill Cook, president of the American School Counselor Association.

“Counselors help ensure that the systems are in place to get students the help they need,” Cook explains. “But schools need social workers, school psychologists, school nurses—all those school-based mental health personnel to support students.”

All Hands on Deck

In ESU 7, Kunze and Rose say community support for their work is strong, and awareness of the severity of the mental health problem has increased. But moving the work forward and being able to focus on “Tier 1,” or preventative strategies, as well as social and emotional learning, and less on reactive measures should be the next step.

“With the heavy loads our counselors are taking on, we need more funding and resources to address our students’ mental health,” Kunze says.

Rose recently represented the Nebraska State Education Association at the state legislature, in Lincoln, when she testified in support of legislation that would reimburse schools and ESUs for specific mental health expenses.

“Rather than delay until an incident occurs and then try to step in,” Rose says, schools can intervene earlier if they hire more counselors and school psychologists and train all staff, including teachers.

That was the goal last year when teachers in the Mojave Unified School District in California were trained to identify warning signs in student behavior. Robinson and colleague Benito Luna-Herrera both considered the training necessary.

“We’re already a steady presence in students’ lives. We have existing relationships with them and their families,” Luna-Herrera says. “And some of these students are in households that are just disasters. Staying at home during COVID just made their mental health worse.”

Even though the state has significantly ramped up hiring for school counselors, those positions have been difficult to retain in California City. And even when counselors are on staff, a teacher shortage has forced them to fill instructional roles.

“It’s been a really tough couple of years,” Robinson says. “We’re all under a lot of pressure, so the training helped. Hopefully the district will invest in more. I don’t think we could have survived if it wasn’t all hands on deck.”

‘We’re All on the Same Page’

Just three hours south of California City lies the Coachella Valley, a desert region known for hosting one of the most popular music and arts festival in the world. It's also known for extreme heat and staggering income inequality. With expensive resorts and clubs nearby, 94 percent of the students in the Coachella Valley Unified School District (CVUSD) live in poverty, with all the adverse childhood experiences and trauma that come with it.

The student population is predominantly Latino, many from families of migrant workers. Already plagued by economic instability, these families continue to struggle in the wake of the pandemic and live in fear of family separation and deportation.

The suicide rate in Coachella Valley far outpaces county, state, and national rates. And the anxiety and sadness that was widespread before the pandemic has only worsened since. Fortunately, CVUSD had already prioritized mental health in their district, committing to a portfolio of programs and initiatives.

“Over the past decade, everybody came together and said, regardless of what our politics are, regardless of whatever our views on other issues are, we all agree that mental health is an important thing that we need to tackle,” says Karina Vega, a K–12 counselor in CVUSD and a member of the Coachella Valley Teachers Association. “Everyone has been 100 percent supportive—the union, the school board, local politicians, and parents.”

Funds from federal pandemic relief packages helped some of the programs in Coachella Valley get off the ground, including the opening of student wellness centers in the district’s middle and high schools in 2022.

In the wellness centers, which Vega helps coordinate, students learn coping skills and can always find someone to talk to.

“[It’s] somewhere for students to put down some of the things they’re carrying,” Vega says. Staff at the centers work with school nurses and campus safety officials and refer students to services in the community. The Latino Commission, a nearby mental health therapy and counseling center, provides on-site therapists for every school.

Through these resources and partnerships, CVUSD is able to triage students so they receive the most appropriate and timely care. That level of coordination is required to meet the complexity and urgency of the crisis.

“These students and their families don’t have the luxury to grieve,” Vega says “There’s too much going on in their lives, too much loss, too much pressure to put food on the table. So the fact that our wellness centers are providing a place for our students to take their grief, for me, is a miracle in itself.”

Even when current grant funding for the wellness center expires, school leaders hope the future of the district’s mental health initiative is secure. The response from staff, students, and parents has been overwhelming, Vega adds.

No Time Left to Lose

Two months after the Lincoln County school board voted to eliminate the social workers’ positions, the district received welcome news. In June, a health clinician at nearby Marshall University struck an agreement with the board.

The social workers would be contracted with a local private health entity to provide services to area schools. Although this is a positive development, the issue of adequately staffing social workers in schools has not been addressed, says WVEA’s Martin.

“We want every county in our state to have the resources they need to support student mental health needs,” she explains. “A better outcome for the Lincoln County situation would have been for the county to utilize funding so that every school would have a social worker.”

The longer it takes to provide rural schools with these necessary resources, says UVA’s Bradshaw, the longer it will take to implement effective prevention strategies.

“We’re playing catch up here. These students need help,” Bradshaw says. “This isn’t just a flash-in-the-pan problem. This is going to be something that is with us for an entire generation of students.”

Resources to Support Student & Educator Mental Health

Get more from