Key Takeaways

- Although 1 in 28 children have a parent in prison or jail, schools still struggle to destigmatize this unique but common experience.

- Education about mass incarceration and training for how to identify implicit biases can help educators learn how to best support students impacted by the criminal justice system.

- Creating affirming spaces at school and identifying community resources can decrease feelings of isolation for students whose parents are incarcerated.

When children are not able to frequently see and talk to a parent in prison, they may often feel alone and unable to talk about what they are going through.

An elementary school counselor in Minnesota, Anna Whooley regularly sees how the stigma of having an incarcerated loved one negatively affects students.

“I see students with a lot of anger, sadness, confusion, or even fear that it may happen to them or the other parent as well,” Whooley says.

Although the United States makes up roughly 5 percent of the world’s population, the country is the world leader in incarceration, negatively impacting millions of families.

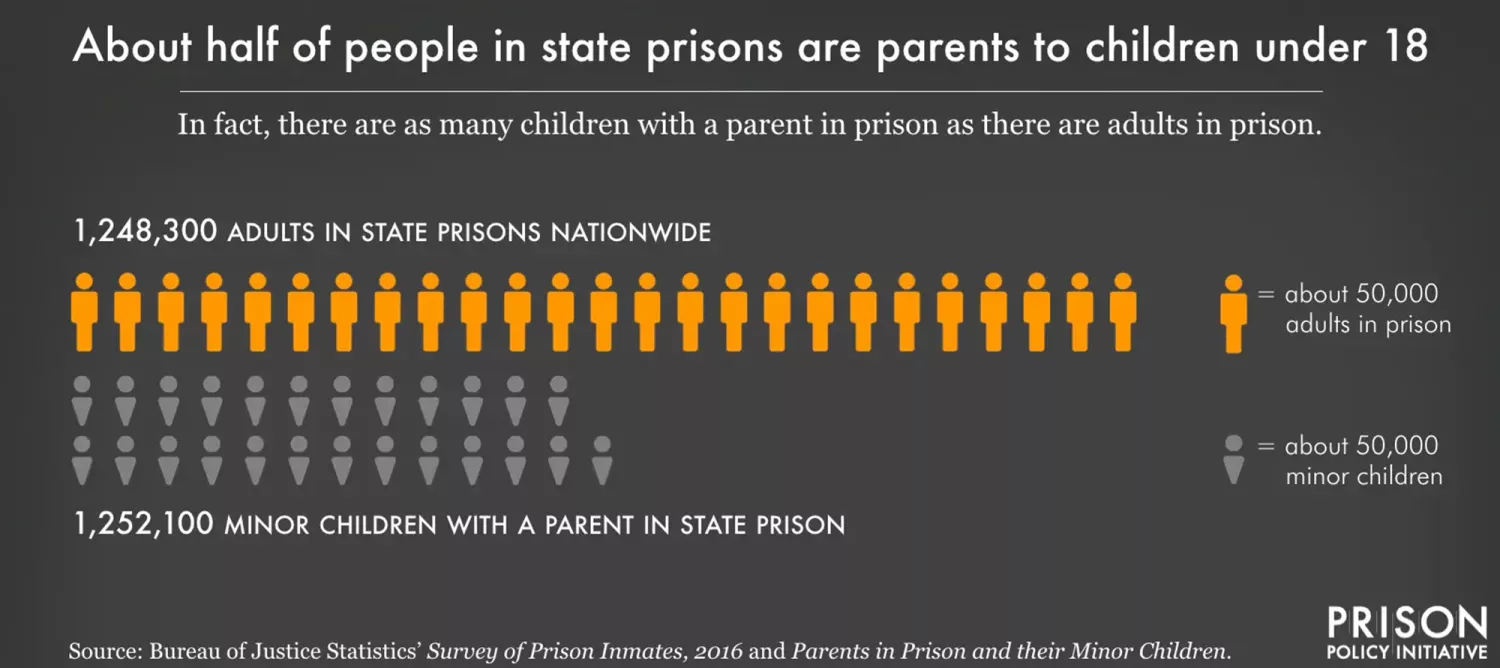

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, roughly half of all incarcerated people in state prisons are parents with children ages 18 or younger. The Annie E. Casey Foundation found that over 5.1 million children in the U.S. have had a parent in jail or prison in their lifetime.

Systemic racism results in racial and ethnic disparities within the criminal justice system, such as racial profiling from the police, racism influencing prosecutorial decisions and even producing harsher sentences. The Prison Policy Initiative also found that Black Americans are incarcerated in state prisons 5 times more than white Americans and Hispanics are incarcerated in state prisons 1.3 times more than white Americans.

Black and Hispanic families are disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration, with 1 in 9 African American children and 1 in 28 Hispanic children having an incarcerated parent compared to 1 in 57 white children. This means that Black and Latino students are disproportionately affected by the lack of resources and services available to help them cope with the emotional trauma of having an incarcerated parent.

Research shows that frequent visits between the child and incarcerated parent not only reduces the likelihood of them being incarcerated again, but it also lowers the child’s experiences of anxiety and depression. Unfortunately, there are several barriers that could prevent families from visiting their loved ones in prison, including lack of transportation and the often far traveling distance to a facility.

When a loved one is in jail or prison, students may process their grief and trauma for this type of loss differently across grade levels.

“It’s an ambiguous loss, which I think makes it difficult [for younger children] because they can’t really wrap their brain around exactly why mom or dad isn’t here and what that means moving forward,” Whooley says.

A Need for Training

While the incarceration of a loved one negatively impacts children, schools may often feel ill equipped to provide support and resources for these students. This is due to a lack of training that not only discusses mass incarceration and its impact on students, but also how to best support students experiencing this type of loss. This includes training for how to create affirming spaces in school, find and offer community resources, respect family wishes, and destigmatize the topic so that students don’t feel alone in this experience.

Training also allows for people to learn more about their implicit biases, meaning the prejudices and stereotypes one may unconsciously carry. This helps educators become more aware of the implicit biases they may direct towards someone incarcerated as well as their child.

Research published in the Journal of School Health finds that implicit biases towards children with incarcerated parents can negatively impact their academic performance. This is especially true when teachers begin to lower their expectations for the child.

“It’s really important to not associate the child with the crime because they are also second-hand victims in this situation,” Whooley says.

Allison Hollihan, a licensed mental health counselor, works as the director of the New York Initiative for Children of Incarcerated Parents (NYCIP) through the Osborne’s Policy Center. In this position, she advocates for a more inclusive and supportive environment for students impacted by the justice system.

“Training is so critical to help teachers understand the issue and the implicit biases that they may not realize they carry,” Hollihan says.

A survey conducted by Cornell University and FWD.us, a criminal justice and immigration reform advocacy group, found that 6.5 million adults have an immediate family member in jail or prison. Additionally, about 1 in 7 adults have had a family member incarcerated for over one year.

This means that there are adults in schools that could connect with students on this shared experience.

“We also always recommend, when working with schools, to identify a couple key people in the school who feel comfortable talking about incarceration,” Hollihan says. “Oftentimes, those tend to be people who also share the experience of having an incarcerated family member.”

Destigmatizing Leads to Peer Support

When working with children whose parents are involved in the criminal legal system, Hollihan noticed that many of them are told not to talk about their parent being incarcerated, making the children feel extremely alone in this common experience.

“People are learning at home that ‘this is not something that we talk about’ and they are learning shame,” Hollihan says. “They come to school, and they are carrying all this weight of the separation and worry of having an incarcerated parent and they feel like they can’t talk about it.”

Knowing this, NYCIP began an afterschool program for students experiencing parental incarceration.

“Creating a space in the school or finding an afterschool program in the community that specifically supports children with incarcerated parents is critical since peer support is so empowering because of the stigma attached to having incarcerated parents,” Hollihan says.

Two girls, both whose father was incarcerated, went to elementary school together without knowing they were going through similar experiences until they began going to the afterschool program.

“Although they knew each other, they really bonded over that shared experience and started going on trips to visit their fathers together,” Hollihan says.

Schools can also consider providing peer group support options for their students.

“In high school, they might understand more of why their parent is incarcerated and that is complex grief and second-hand trauma, so having a counseling group could really help support them,” Whooley says.

Creating Affirming Spaces

Another powerful way to reduce the stigma of incarcerated parents is by acknowledging in the classroom the various family dynamics a student may be involved in.

“Using simple phrases like ‘parents that don’t live with us’ in conversations can really help with making people feel included,” Whooley says.

It is also recommended for school libraries and teachers to keep books appropriate for their grade levels that discuss the unique but common experience of having a parent in jail or prison.

“I think that having a book that represents that experience appropriate for their age level is so important because that might be the only place where they see that experience reflected,” Whooley says.

To help educators, NYCIP has created a list of book recommendations and noted the age group they are appropriate for.

“I would encourage librarians and teachers to have those on their shelves so that children can seek them out on their own or if they disclose, they can be encouraged to check out the book,” Hollihan says.

Respecting Requests of Families

Recognizing that every family and situation is different by asking what the family needs is critical to providing necessary support.

“It’s important to meet the family where they’re at,” Whooley says. “If they are in a place to talk about it and want to have that conversation, don’t shy away from it.”

“There are a lot of challenges and it's not easy for these children to navigate the experience, but when people believe and invest in them and have high aspirations for them, they will succeed,” Hollihan says.

For more information about how to create affirming spaces for students whose parents are involved in the criminal legal system, visit NYCIP’s website of resources and tips for educators.