Key Takeaways

- Cellphone bans in schools are proliferating in the face of mounting evidence that the devices are taking a serious toll on students' ability to focus in the classroom and their overall mental health.

- District policies can be vague, inconsistent, and difficult to enforce.

- Educators and their unions have been advocating for tougher and more uniform approaches that allow them to spend more time teaching in their classrooms, and less time policing cellphone use.

90%

83%

Two years ago, Devon Espejo, an art teacher at San Marcos High School in Santa Barbara, California, attached a numbered storage shelf, made from wood and with 36 pockets, on her classroom wall. Most of her colleagues didn’t do the same, that is until the shelves, or at least the intent behind them, became district-wide policy in the 2024-25 school year.

“It’s better now that we all have them,” Espejo says. “A more uniform approach will help us control these devices in the classroom.”

The devices are, of course, cellphones, and the pockets hanging on the wall are makeshift “cellphone hotels.” High school students in Santa Barbara United School District (SBUSD) must park their phones in the holders before taking their seats—making the devices out of reach, out of sight (more or less), and (hopefully, eventually) out of mind.

Better late than never, says Espejo. She and her colleagues were done competing with smartphones for students’ attention.

“In addition to all the other things we're expected to do, we were policing cellphones by implementing our own rules,” Espejo explains. “It was exhausting and not what I am here to do. I don't want to be the phone police. I want to teach.”

SBUSD is just one of a rapidly growing number of districts across the country that have enacted some form of cellphone ban in schools.

To most educators, there is no compelling argument against taking these steps.

“It seems that everyone—including parents—agree that excessive phone use is detrimental to teenagers,” says Cassandra Dorn, a high school teacher in Red Bank, New Jersey. “We know about the negative effects on academic performance and mental health. Yet, as a society, we really haven’t had the collective will to address the problem.”

In many communities, it has been up to educators and their unions to make the case that the status quo is unacceptable.

“No one else was going to do it,” said Noelle Gilzow, a science teacher in Missouri and president of the Columbia Missouri National Education Association (CMNEA). “Our number one job is creating a sound and effective learning environment. Cellphones were making that impossible.”

Enough is Enough

As of September 2024, 15 states have passed laws or enacted policies that ban or restrict students’ use of cellphones in schools statewide. And seven of the nation’s 20 largest school districts forbid use of cellphones during the school day.

The new momentum behind regulations at the state and local level did not happen overnight, says Victor Pereira, a lecturer on education and co-chair of the Teaching and Technology Leadership Program at the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. “This is really just the culmination of a decade and a half of schools trying to negotiate cellphone policies, trying to solve the problem of how much it distracts students from being engaged in learning.”

As smartphone ownership among young people accelerated 15 or so years ago, districts banned the devices. A few years later, under pressure from parents and willing to at least try to accommodate new technologies, many reversed course—even as the word “addiction” began to be associated with teenagers’ reliance on their smartphones. This dependency worsened during remote learning after COVID shut down schools—and followed students back into the classroom.

A 2023 student survey by Common Sense Media found that, on a typical day, the average student receives hundreds of notifications on their phone, about a quarter of which arrive during the school day. That’s a lot of 'pings’—and distractions—during instructional hours.

“Students are so reassured by that sound. They're flipping it over and looking at the screen without even realizing that they're doing it,” says Gilzow.

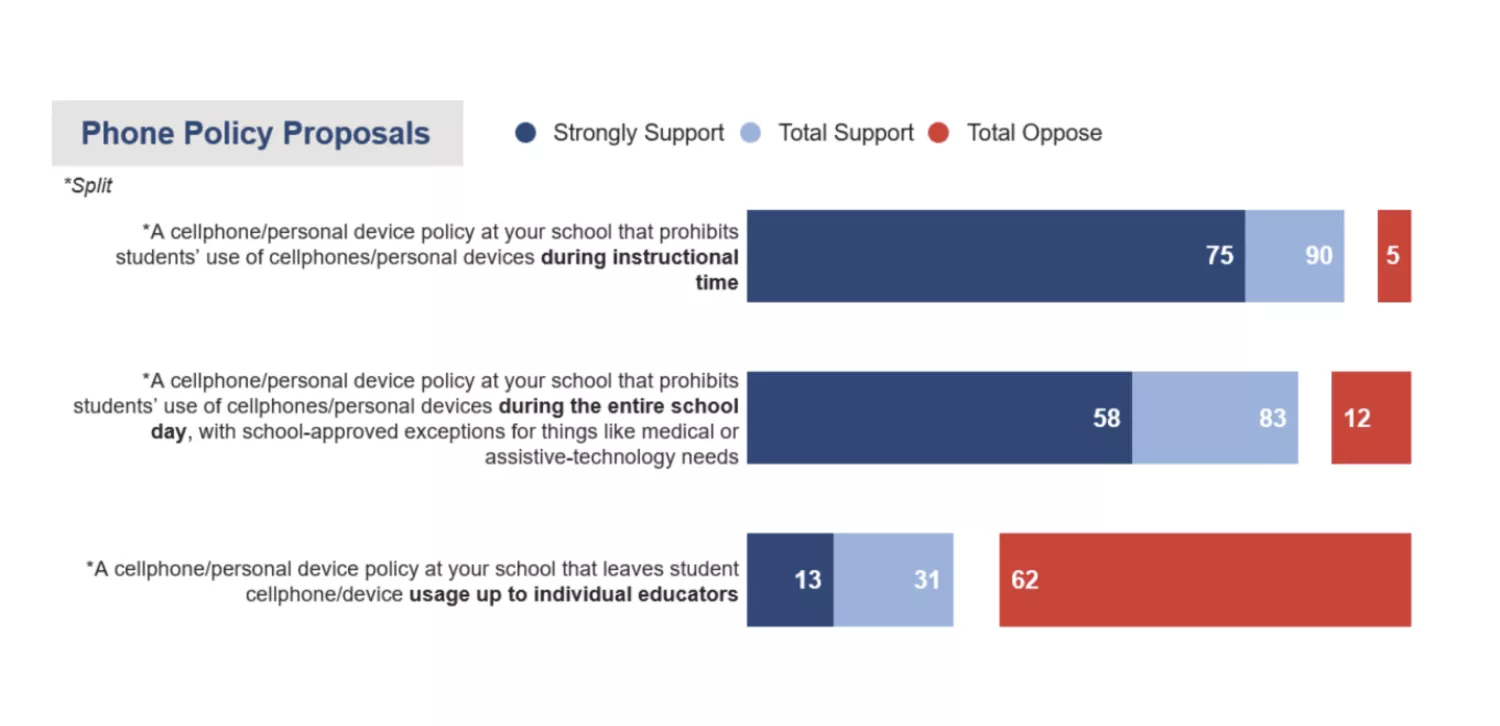

A 2024 National Education Association (NEA) poll found that 90 percent of teachers support prohibiting student cellphone use during instructional hours. Seventy-five percent favor extending restrictions to the entire school day.

Educators are deeply concerned about the impact social media has on students' mental health, and believe those negative effects are another reason to limit access to phones at school. But, according to the NEA survey, the biggest concern about social media use in school is the constant disruptions to learning.

And it’s not just social media.

“We’re competing with Netflix, FaceTime, texting,” Gilzow said. “They’re even watching March Madness!”

Kim Tilton, a science teacher at San Marcos High School in California, agrees. “If the phone is in their hands, there is zero engagement, zero focus. That’s the experience we were all having, and it became a major working condition issue for us.”

‘A Teacher-Led Movement’

While acknowledging the challenges posed by cellphones, too many districts and school leaders avoided enacting any sort of formal restrictions. Educators were usually told that a uniform policy would be complicated, controversial, and even unnecessary. Do what is best for your individual classrooms. Enforce it yourself. And good luck.

“There was no discussion at all,” Tilton recalls. “The district didn't really want to get involved or even make any effort to get feedback from us about the impact of the devices. This had to be a teacher-led movement.”

Tilton, who is an at-large representative for the Santa Barbara Teachers Association (SBTA), stepped into the leadership void. She sent out a survey to members that asked about, among other topics, their views on cellphone use in schools.

SBTA presented the data to the district and successfully lobbied the district to take the issue seriously. In 2022, discussions between SBTA and the district led to a new policy called “Off and Away.”

After a slow roll-out, the policy was fully launched in 2024, with "phone hotels" in every classroom across three high schools. Unless a student has a health exception, all phones must be parked before class begins. The devices stay there during restroom breaks, but students can get their phones after class and use them during lunch and other breaks.

“Initially, ‘Off and Away’ was more of a suggestion,” says Devon Espejo. “But the district came out stronger this past year, so the hotels became a uniform policy.”

At Red Bank High School in New Jersey, English teacher Dorn piloted her own cellphone hotel program (an over-the-door shoe holder) in her classroom in 2023. With the support of her colleagues and the administration, the program became school-wide policy the following year. “An overwhelming majority of my colleagues see phones in the classroom as a major hurdle to effective instruction,” Dorn says.

A collaboration between the Columbia Missouri National Education Association (CMNEA) and Columbia Public Schools led in 2024 to the adoption of new school cellphone regulations.

During the lead-up to contract bargaining, CMNEA surveyed members about their top issues. Unrestricted student access to cellphones was cited by 61 percent as the working condition issue of greatest concern. Educators asked the district to devise a new policy restricting access. Despite officials’ reluctance, CMNEA was persistent, and in April 2024, the district rolled out new regulations.

Beginning in 2024-25, cellphone use is not allowed in any high school classroom in Columbus and must be “out of sight” during instructional time. In middle schools, cellphone use will not be allowed at any time during the entire school day.

With cellphone use in schools emerging as a working condition for educators, policies governing their use may begin to appear at the bargaining table. In 2022, Ohio's Wooster Education Association (WEA) successfully advocated for inclusion of language in their contract that requires the district to solicit WEA’s input when updating its cellphone policy.

Pushback from Parents?

When designing and implementing a new policy, the voices of all stakeholders must be considered, says Victor Pereira.

“You need to listen to everyone - educators, students, family, parents, and school leaders. This is a complex issue, and all those folks come with very different perspectives.”

Consistency is also critical.

“What we had in place was piecemeal, and it varied widely across the district,” Gilzow said. “If the policy isn’t clear and consistent in a school, you get a slippery slope. You have the ‘cool’ teacher who lets me use my cellphone in class. And then there is the ‘mean’ teacher who does not. Not only will the policy fail, but it also confuses students and can set up a bad dynamic, an unhealthy culture in the building.”

Quote byDevon Espejo , Art Teacher, San Marcos High School

Any plan to restrict cellphones will draw concerns from at least a few parents. A recent poll by the National Parents Union found that 78% of parents want their children to have cellphone access during the school day in case there is an emergency.

In Santa Barbara, however, parents have been largely supportive, although that could change. They have legitimate concerns about being able to reach their kids for a variety of reasons, but schools in the district have systems in place to handle emergencies, along with potential workarounds to provide another access point for communication.

“Parents are struggling with monitoring and dealing with these devices at home, so they know what we are dealing with,” says Espejo. “We understand why some parents are uncomfortable with the policy. But if they were to sit through a class with kids who have access to their phones and then sat through one where phones were not allowed, they would endorse it.”

Patching the Cracks

Enforcement is another perennial challenge. Students can be tricky. Some will lie about not having a phone, or they will put other things in the hotels to try to trick teachers, reports Espejo.

“Many students are still glued to their phone,” said Dorn. At Red Bank, Dorn saw the policy’s effectiveness decline a bit over the course of the 2023-24 school year. “Overall, I would say it was a qualified success, but there was some ‘discipline fatigue,’ the red tape involved in referrals. It can become a question of priorities, and some chose the priority of teaching rather than policing.”

In 2024, however, the administration decided to extend the restrictions. Students must still use the “cell hotels," but also are prohibited from carrying or using phones in the hallways. “The school is taking this seriously and hopefully that will make a difference,” says Dorn.

At San Marcos, Espejo would like a system that sends parents a text if their child breaks the rules or has their phone taken away. The district already has a system of notifying parents via text if their student is absent or late to school.

“I would love for a way to have some kind of automatic way to send messages to parents that’s just like one click,” she says. "Otherwise, there’s too much red tape.”

Even though the policy in Santa Barbara has been in full effect for only a few months, the reviews from educators are positive. They report greater engagement, lower stress levels, and, on the whole, widespread acceptance.

“It was a long journey, but the district did listen to us,” Tilton says. “That's the power of having a strong union. Our collective voice brought us a new systemic cellphone policy. But cracks are going to appear, and we just need to patch them, keep everyone on board. We will continue to lead on this because our feedback, our ideas should be front and center. We know what works and what doesn’t.”