Key Takeaways

- As the educator shortage reaches crisis levels, listening and learning from those who are staying could help end the shortage and lift up the profession.

- When NEA asked its members about job satisfaction, most said they were very satisfied with their jobs but very dissatisfied with working conditions.

- Three educators explain why they are staying in the classroom and how their union is working to make them feel valued, trusted and respected.

The Lessons Are Clear

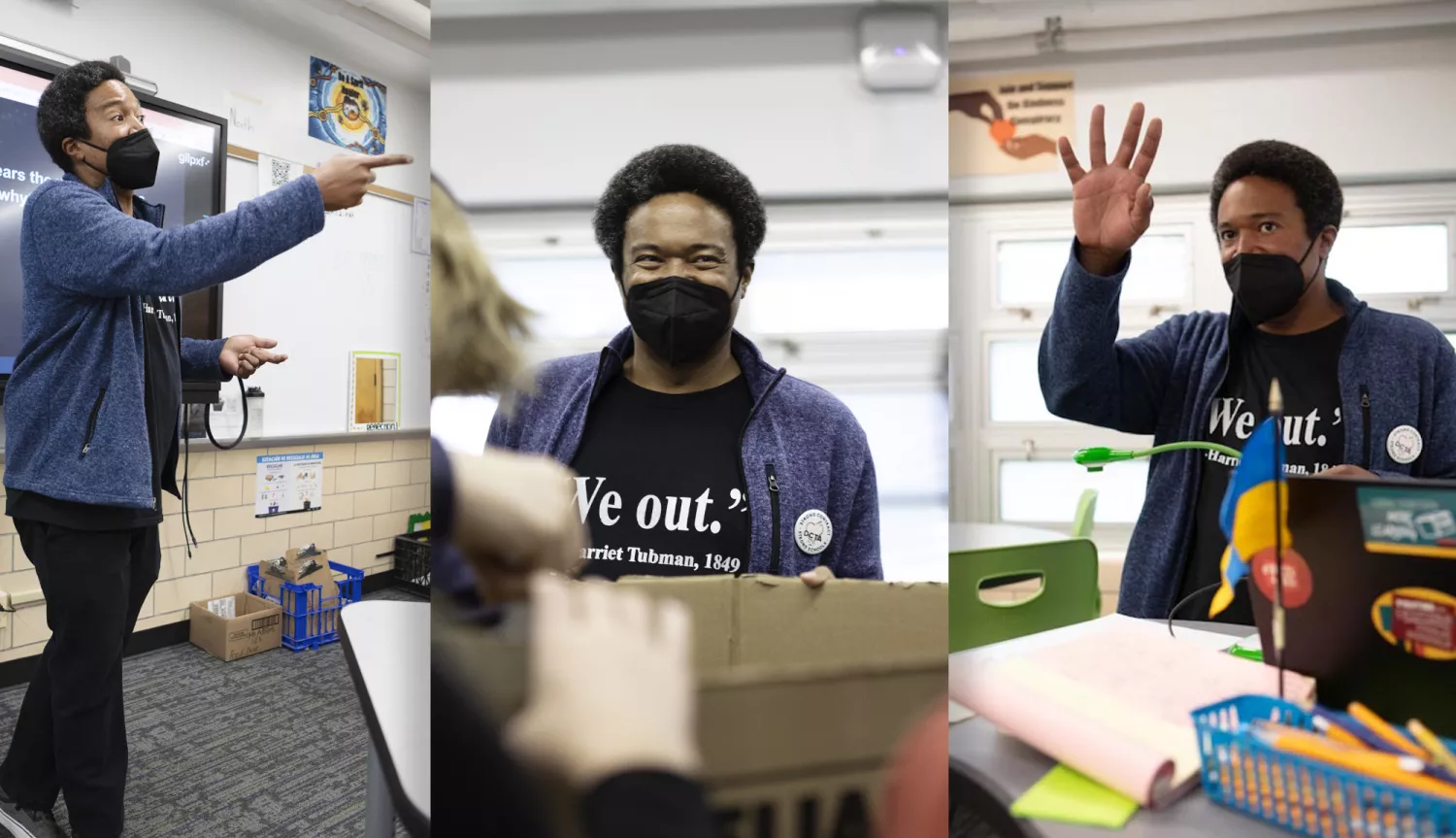

Kevin Adams has moments when he considers packing up his classroom and starting a new career. He realizes no job is without its challenges, but the education profession is inordinately demanding without much financial reward. Heap on the problems the pandemic created and, Adams acknowledges, it can start to feel hopeless.

“Sure, I flirt with the idea of leaving,” says the Denver social studies teacher. “It’s especially tough when you don’t feel your work is respected by the community, or even sometimes by the people you work for. You wonder, ‘Do they realize the sacrifices we educators make? Do they know what we’ve given up in order to give our all to this job?’”

But then his thoughts go back to his students. He remembers what it’s like to watch them grow and evolve, to see the sparks of understanding light up their faces, to interact with their spirited young minds, and even to hear their silly jokes. There’s joy and fulfillment in each day at his middle school— enough of it to tip the scales. And so he stays.

“That is the number one reason I’m still here, hands down,” Adams says. “It’s the kids.”

Last year, record numbers of educators left the profession. In a 2022 NEA survey of its members, 55 percent said the pandemic made them more likely to leave the field at the end of the school year. Some educators were so fed up that they made the tough call to leave midyear.

The educator shortage has reached crisis levels, threatening to push even more people from the profession because of stress and exhaustion. Policymakers can learn a lot by listening to the experiences of educators who have hit their limit.

But this is a story about those who stay and why. These educators, too, have powerful insights to share. Listening and learning from those who choose to continue could help end the shortage and lift up the profession, for teachers and for education support professionals (ESPs).

When NEA asked members, “How satisfied are you with your job?” and, “How satisfied are you with conditions facing educators these days?” educators said they were very satisfied with their jobs but very dissatisfied with the conditions. And not by a small margin—there’s usually a 40 to 50 point difference in the responses.

The lesson is easy to understand for those who pay attention: Improve working conditions and educators will stay.

So what do educators want most? Time to connect and collaborate with trusted colleagues; the agency to create lessons that work for their students; the autonomy to make job-related decisions based on their expertise; and, of course, gains in professional pay. They also want to feel the power of their voice and the strength of the union behind them to improve conditions.

Most educators are called to the profession because they love working with students. But feeling trusted, respected, and valued is what will keep them there.

A Need for Representation

Adams brings critical representation to his students. As a Black male educator, he feels a responsibility to remain in the classroom for the benefit of his students of color.

“It’s important to have folks like me in education,” he says. “I understand that they might not get another teacher who looks like me, who connects with them and advocates for them the way I have.”

In 2015, Adams launched a podcast, Too Dope Teachers and a Mic, with colleague Gerardo Muñoz, the only other male teacher of color in their school. They had long traded recommendations for podcasts, often discussing comedy and insights from a favorite weekly podcast, Denzel Washington Is the Greatest Actor of All Time Period.

“The hosts engaged in very silly, esoteric conversations, but also spoke in a serious way about race and representation in Hollywood,” Adams says.

Similarly, race and representation in education is top of mind for Adams and Muñoz, and they often found themselves exchanging a lot of glances during staff meetings.

“Sometimes things that were said were inequitable, sometimes even a little racist,” Adams says. “After the meetings, we’d carry on the conversation in one of our classrooms, talking about things we noticed, how people talked about the students, and how it impacted us and our experiences as male teachers of color.”

It soon occurred to the friends that others might want to listen in on these conversations. Muñoz did a lot of research on how to produce a podcast, and before long, Too Dope Teachers and a Mic was born.

Get the GM Educator Appreciation Offer

- Learn More

Connection and Collaboration

The ability to talk about his experiences has been cathartic for Adams, and he says carrying on the work of educational equity by reflecting and sharing on a deeper level has also contributed to his staying power. “It calls me to think about my role as a teacher differently,” Adams says.

That kind of reflection creates deeper meaning and purpose for educators, which helps them build resilience. Another factor in staying power, Adams says, is finding your people.

“You might not always agree with them 100 percent, but if you have similar philosophies about the work, colleagues can really push you to do something different and new,” he says. “I’ve changed as a teacher in my practice and how I interact with students. That kind of relationship [with colleagues] holds you accountable.”

Not everyone has to be in your inner tribe. Even more casual relationships can make a big difference.

“I rely on those times when we come together to talk about our struggles honestly and openly,” he says. “When you realize, ‘Oh, they’re having the same problem! Oh, it’s not just me,’ it helps a lot. There are so many times when we feel we’re in isolated silos, so when you can connect with colleagues, you get that bigger perspective that makes you feel less alone.”

Creative License

Niels Pasternak is an Oregon special education teacher who works with students who have profound needs. There are teenagers and students in their 20s who are learning to walk or talk, feed themselves, use the bathroom, or operate wheelchairs. It is arduous work for both educator and student, but the rewards are immense.

His positive relationships with students—and the joy of watching them hit new milestones—are what keep him coming back year after year. Making a difference in someone’s life is at the heart of education, and that inspires and motivates Pasternak and many others in the field.

He also has self-designed strategies that help his students learn and progress. And, importantly, he has the freedom to use them as he sees fit.

“When we’re able to tap into our creativity, educators are going to be happier and more fulfilled,” he says. “We don’t want to be told our students must consume information this way, and teach these standards that way, and have every 15 minutes planned for us. Our systems fail when we try to create obedient drones out of students and educators. We need to trust educators with creative control.”

Pasternak is aware of how frustrating the system is; how quickly it can grind you down.

“Assembly line education is soul-crushing, and that trickles down to the kids,” he says. “Rather than a model in which everyone teaches and learns the same things and passes the same tests, we should adopt a model where educators can allow students to pursue what lights a fire inside their imaginations and sparks curiosity. Success is about developing our strengths, not eliminating our weaknesses.”

What do educators really want to feel appreciated?

Quentin

Kathy

Jamie

Kristin

Susan

Katherine

Lakeisha

Margaret

Mary

'You're Worth It'

Suzanne Smith sometimes finds herself singing in the hallways without even thinking about it. That’s how she finds her calming state of “flow.” It’s second nature and stress relieving, says the Grenada, Miss., middle school teacher, who is also the music director at her church.

She knows the term “self-care” is overused, and it isn’t a cure-all, but finding a way to divert attention from the negative and focus on something you enjoy helps a lot.

“[Music] puts my mind in a better place,” she says.

But a big raise has given her even more reasons to sing. Last year, thanks to the advocacy of the Mississippi Association of Educators and members like Smith, Gov. Tate Reeves signed into law the largest teacher pay raise in the state’s recent history.

Teachers in the state, long among the lowest paid in the nation, will receive an average increase of more than $5,000 in the 2022 – 2023 school year, which is about a 10 percent pay hike on average. Teacher assistants will receive a $2,000 raise in the same school year.

“It’s huge,” Smith says. “In all the 30 years I have been teaching, this is the largest we’ve ever gotten at one time. I also appreciate the fact that our legislators appreciated us and cared for us enough to push for that.”

Smith, too, has considered leaving, wondering if she needed a change from the strain of teaching. She stayed because it’s what she’s wanted to do ever since she was a little girl, and she couldn’t imagine a career she would enjoy more.

But having her union work with her legislators to finally recognize educators’ value does wonders for morale and the desire to stay. Some educators had been commuting to Alabama to work. Soon after Mississippi’s raise, Alabama raised its own teachers’ salaries to compete and try to ease that state’s shortage.

Under the new Mississippi law, teachers will also receive annual step increases of at least $400, with larger increases in every fifth year and a more substantial bump at 25 years. The increase will not only attract more people to the profession, but it will help keep them there.

“Some teachers are saying it’s not enough,” Smith says. “Is it ever enough? The fact that we’ve come this far is a milestone, and will set a precedent. We’ll only go up from here, and I think we’ve shown what we are worth and why we deserve professional pay. Now the rest of the country is watching.”

Back in Denver, Adams is a member of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association bargaining team. He says the process is sometimes disheartening, but it’s also empowering. He and his colleagues are determined to create an environment that will make educators want to stay—better working conditions, more resources for schools and student mental health, and bigger paychecks.

“That becomes the inspiring thing—working for what it could be in public education,” he says. “The world I want to work in doesn’t yet exist, but the work I’m doing with my union and my colleagues is to create the right systems for teaching and learning, the ones we dream about seeing.”

And so he stays, feeling ever more optimistic as we head back to school.

“Around the corner there’s hope,” he says. “Things get better and change.”

Get more from