Key Takeaways

- Incidents of antisemitism on U.S. college campuses have increased since the Israel-Hamas war began.

- Even before this recent wave, many faculty were working to educate students on the roots of antisemitism.

- Education is key! Check out NEA’s compiled resources on antisemitism and learn how to talk about the Israel-Hamas war without crossing the line into antisemitism.

At Cornell University, in New York, anonymous threats flooded an online message board: “If you see a Jewish ‘person’ on campus, follow them home and slit their throats,” said one. At Tulane University, in Louisiana, two students were assaulted as another attempted to burn an Israeli flag. At the University of Maryland, students found “Holocaust 2.0” chalked onto campus sidewalks.

These are just a few examples of the 843 incidents of antisemitism on college campuses that Hillel International has tracked since the Israel-Hamas war began in October 2023. It’s a 700 percent increase over the same period last year, and amounts to what the Biden administration has called an “alarming rise” of antisemitism on U.S. college campuses this fall.

Meanwhile, many NEA faculty and staff are responding and will continue to respond in the ways they know best: Through higher education and art, and by creating supportive and creative classroom spaces that foster learning.

“Educators have a professional responsibility to teach inclusion and respect for different beliefs and religions,” said NEA President Becky Pringle in November, as anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim bigotry and violence rose. “We also have a moral imperative to educate people about antisemitism, Islamophobia, and about how to support Jewish and Muslim students and communities.”

Teaching about the “oldest hatred”

“People have said to me, ‘How are you going to teach about that!? That’s volatile!’” says Nancy Koppelman, a professor at The Evergreen State College in Washington State, who teaches about Israel and the history of antisemitism. “But I’ve never had a problem in class. Ever. And I think that’s, in part, because when I was a student here at Evergreen State in the 80s, I had great faculty who were able to generate learning without engendering bad feelings. I learned from them—and I’ve been able to do that, too.”

A small number of U.S. colleges and universities offer courses about antisemitism, often through Jewish studies departments. There are only about 90 such programs nation-wide. At Evergreen, Koppelman was moved to develop her class a few years ago, after two incidents. The first was when the American Studies Association, of which Koppelman was a member, voted a decade ago to boycott Israeli academic institutions. “It was one of the first [boycotts] of its kind,” she recalls, “and it really upset me because I think academic boycotts are counterproductive to change. If there’s anything you shouldn’t boycott, it’s the exchange of ideas.”

The second impetus was the terrorist attack on Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, in 2018, when an antisemitic gunman killed 11 people during Shabbat services. “I was devastated and shocked and I felt like I needed to do something,” she says. At the same time, Koppelman lives in an area of the country where there are very few Jews—the Jewish population in Thurston County, Wash., is the same as the Jewish population worldwide: just two-tenths of 1 percent.

Addressing Antisemitism

With the rise of White nationalism, the number of antisemitic threats in K-12 schools and on college campuses has escalated, fueled even more by the Israel-Hamas war. Check out these resources, compiled by NEA, to address antisemitism.

“I see a lot of ignorance about Jewish topics and have for a long, long time. Since I’m in the business of challenging ignorance—that’s my job—I applied for a fellowship at Brandeis University,” Koppelman recounts. What she learned at Brandeis, plus her 30 years studying and teaching history and ethics, helped her to develop Evergreen’s courses on antisemitism and on Israel.

She began teaching about Israel in 2020 and about antisemitism in 2022—before the recent proliferation of antisemitic incidents on U.S. campuses—but antisemitism has been present on campuses and elsewhere for a very long time. Indeed, the Southern Poverty Law Center calls it “the oldest hatred,” and points to how antisemitism undergirds other hatreds and extremist ideologies, especially the White power movement.

Talking about the War

Since the Israel-Hamas war began in early October, Jewish college students report increasing incidents of antisemitism on their campuses, and increasing feelings that they aren't physically or emotionally safe. But criticism of Israel and its war in Gaza need not cross the line into antisemitism. Indeed, Israelis are among Israel's harshest critics, much as some Americans are most critical of their country, says Koppelman. She suggests five ways to prevent criticism of Israel that crosses the line. They are:

- Be as specific as possible. Indicate which of Israel’s policies you are upset about, and the specific actors or government officials involved.

- Reject rhetoric or images that could remind people of the classic antisemitic stereotypes.

- Reject speaking about “the Jews” as if they are the same as the Israeli government and avoid describing Jews as “the Zionists.”

- Don’t expect Jewish people to have a view on the conflict or ask them to justify or condemn Israel’s actions.

- Don’t permit your criticism to become censorship. Critics of Israel and supporters of Israel need to talk and listen to one another.

The Power of “I Am a Jew.”

Hearing antisemitic speech isn’t anything new for City University of New York professor Rebecca Shapiro—but she realized a few years ago that, among her students, it often stems from ignorance, not necessarily hatred. “A few years ago, I was talking to my students about ethnicity, and I told them I was a Jew. One of them looks at me and says, ‘Are Jews American?’” recalls Shapiro, who teaches at City Tech in Brooklyn, one of CUNY’s 25 campuses.

“It finally dawned on me, [my students] live in Brooklyn, they see Jews, but they never talk to them,” says Shapiro.

Shapiro welcomes any student’s inquiry—no matter how bizarre—about being a Jew. Her goal is to enlighten, educate, and also to make clear that Jews are a diverse people who don’t all look alike and think alike, act the same or even believe the same.

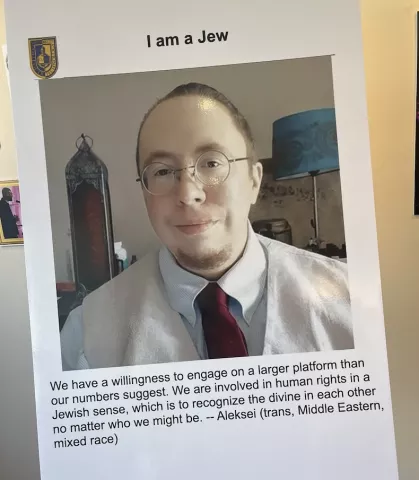

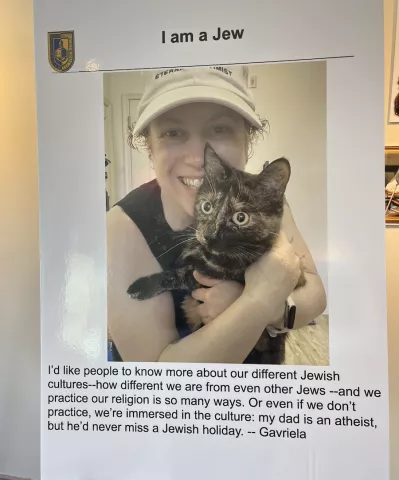

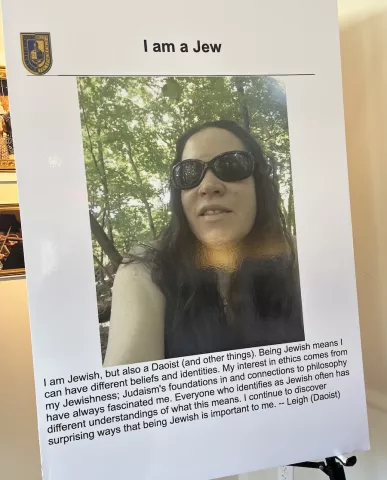

In September, with grant money awarded to CUNY from Hillel International’s Campus Climate Initiative, Shapiro and professor Keith Muchowski curated a photo and text exhibit called “I am a Jew,” which was displayed at City Tech. [It’s currently on exhibit on Washington, D.C.] The exhibit features portraits and personal statements that showcase the racial, ethnic, and religious diversity among Jewish people.

To prompt their responses, Shapiro asked each participant three questions: 1) What is it like being a Jew in America now? 2) What do you like about being a Jew? 3) What do you think people who aren’t Jews need to know? In their responses, Jews of different races, ethnicities, ages and sexualities talked about feeling “othered and unsafe,” about delighting in Jewish food and comedy, about fighting for justice and equality, and about feeling overlooked because they don’t “look Jewish.”

“Every single person’s [response] was different and, at the same time, they’re all Jews,” Shapiro says.

Raising Awareness

Today, not only are more Jewish college students experiencing antisemitism, but there’s a disconcerting gulf between the percentages of Jewish and non-Jewish students who see and recognize it.

The current lack of recognition among non-Jewish students points to a lack of education about antisemitism, says Koppelman, about Jews, and about Israel. And it’s okay to not know everything all at once, she tells her students—most of whom are not Jewish. “I always say that the smartest thing you can say as a student is, ‘I don’t know,’” she says.

Frequently, Jewish topics are reduced to two 20th century events: the Holocaust, which killed 6 million European Jews, a population loss that still hasn’t been recovered, and the establishment of Israel. In Koppelman’s courses, students start centuries earlier, as they learn about the history of antisemitism and the ancient and medieval roots of common stereotypes. “One thing I tell them right away is that there’s a lot behind what they see in the present. I explain what ‘presentism’ is, the tendency to look at the past through current values and ethics, and then being unable to understand what belief and faith meant in the ancient and medieval worlds,” says Koppelman. “I want them to learn how people thought before the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment (17th-19th centuries) brought rational thinking and modern science into the center of historical change.”

They learn that some of the prejudice against Jews has its roots in the 4th century’s Christian empire building—and how that prejudice continued in new forms through the centuries until the election of Hitler in 1933. The stereotype that Jews are all geniuses or masterminds? Students learn it has its roots in the exile of Jewish people from Jerusalem in the year 70. Without a physical place to practice their religion, Jews turned to the Torah (the Hebrew Bible, or Five Books of Moses) to keep Judaism alive—and so everyday Jewish people, mostly men, became literate long before most others.

These are the kinds of tropes that Koppelman’s students explore in her classroom—and during a daylong trip to Seattle’s Holocaust Center for Humanity—as they seek to understand antisemitism. Her goal? It’s decidedly not to create activists, she says. The goal is a non-partisan education, pure and simple.

“Over the years, I have seen what ignorance produces: an atmosphere where antisemitic ideas can live and thrive,” she says. “Ignorance that goes unchallenged is simply out of place on college campuses.”