At Old Mill High School in Millersville, Maryland, Sunny Deitrick’s classroom serves as a haven for newcomer students. Here, first and second generation teenagers from different countries meet to study the English language, share photos from their native lands, commiserate over irregular verbs, and on some occasions to eat cake.

At Old Mill High School in Millersville, Maryland, Sunny Deitrick’s classroom serves as a haven for newcomer students. Here, first and second generation teenagers from different countries meet to study the English language, share photos from their native lands, commiserate over irregular verbs, and on some occasions to eat cake.

"I have tres leches cake,” Deitrick says to the dozen or so students, most of them Latinos from Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Puerto Rico. An earlier group who hail from Kenya, Pakistan, Korea, Ivory Coast, and Syria had just shuffled out to their next class where they will join classmates who for the most part were born and raised in this rural area of Anne Arundel County.

“Who wants a slice of cake,” asks Deitrick, Old Mill’s lead teacher for ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages). “Miss D,” as students know her, holds up a slice of the Latin American “three milks” cake as an opportunity for what she calls a “teachable moment.”

“Okay, who can tell me the English word for leche,” she asks.

As Congress rewrites the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) – also known as No Child Left Behind (NCLB), ESOL students at Old Mill and across the nation are experiencing fewer teachable moments like those Deitrick and most teachers espouse in their classrooms. Why? No time.

Instead, hurried students are being put through a regiment of word drills, grammar exercises and rote memorization designed to arm them with basic facts and test-taking skills. This approach of teaching to the test – repetition without full comprehension – is designed to help students score well on federally mandated multiple-choice tests.

“These students have to somehow go from zero English language to proficient within two to three years,” says Deitrick, a member of the Teachers Association of Anne Arundel County (TAAAC). “They have to be able to pass rigorous courses as well as a high stakes test.”

Under NCLB, teaching methods in many ESOL departments have shifted from employing natural language learning techniques toward strict test-prep strategies. These methods have one goal: get students to score well on standardized tests.

“This is very difficult for these kids, especially if they have no background knowledge of a particular content area,” says Deitrick. “We as teachers have to continue to encourage our students to learn in all their classes while promoting the benefits of speaking English.”

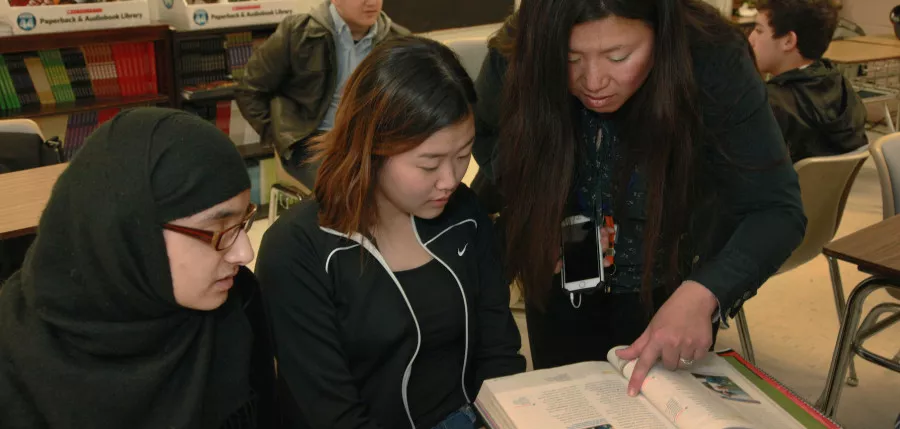

Seventeen-year-old Rozina Ahsan with teacher Sunny Deitrick. After three years of study, Rozina learned English and exited the English Language Acquisition program last year. She is now an ESOL student aide.

Seventeen-year-old Rozina Ahsan with teacher Sunny Deitrick. After three years of study, Rozina learned English and exited the English Language Acquisition program last year. She is now an ESOL student aide.

While some ESOL students arrive in the U.S. intellectually ready to soak up a second language, many arrive with little or no schooling. Some of these students have spent years in refugee camps where there was no school. Others have suffered the consequences of living in countries ravaged by war or revolution. As a result, many can’t read or write in their own language.

After relocating to the U.S., whether they know the difference between a noun and verb or not, newcomer students will likely be tested in English. Even more, their school will face the consequences of their scores if they fail.

“It makes little sense to administer high-stakes tests in English to students who are still learning English because these tests can’t accurately measure what students know,” says Sharon Adelman Reyes, a former teacher and principal who now serves as program director for DiversityLearningK12, a consulting group that conducts professional development training and publishing. “Educators and kids are being judged, often unfairly, by scores on these inappropriate assessments.”

Rather than closing achievement gaps and providing equal opportunities for all students, says Reyes, NCLB has turned schools into test-prep factories.

“Teachers of English learners are under enormous pressure to focus on preparing students to pass tests,” says Reyes, who has worked with K–12 schools serving low-income communities to improve curriculum and instruction in ESOL, dual immersion, transitional bilingual education, and literacy. “Creative teaching and curriculum are falling by the wayside, demoralizing teachers, and encouraging some of the best to leave the profession.”

Reyes says what often takes the place of high-quality bilingual teaching are prepackaged, commercial programs that stress skill-building approaches to language teaching and transmission-model teaching.

“These programs are really just a glorified form of test prep,” says Reyes, author of Engage the Creative Arts: Instruction for English Language Learners, and the more recent, The Trouble with SIOP (with James Crawford). “Assessments can and should play an important role for English learners and, indeed, for all students. But they should be designed to provide information that’s useful to teachers in improving instruction and meeting the needs of individual kids – not to serve half-baked “accountability” systems that serve primarily political purposes.”

The original purpose of the 1965 act was to help level the playing field for our nation’s most vulnerable students—including children living in poverty, students with disabilities, and English language-learners (ELLs). Instead, ESEA has perpetuated a system that delivers unequal opportunities and uneven quality to students, making it impossible for educators to teach and inspire students from different countries and heritages. By law, states are allowed to test ELLs in a language other than English for up to three years, but not many do.

“Few states offer tests in Spanish or other native languages,” Reyes says. “Even when they do, these assessments are inappropriate for the vast majority of ELLs, who are taught exclusively in English.”

Even the Department of Education, says Reyes, does not pretend that current tests "are valid and reliable for ELLs – that they consistently measure how much students really know. Yet, they are still being used for high-stakes purposes.”

At Falls Church High School in Virginia, paraeducator Christopher Robinson typically spends about 75 percent of his workday helping a variety of ESOL and other students to learn how to read and write English.

“A lot of students in the same class are working at different reading and writing levels,” says Robinson, special programs instructional assistant and member of the Fairfax Education Association (FEA). “ESOL students are brand new to the country and we often don’t know enough about their background at first.”

Instructional assistant Christopher Robinson

Instructional assistant Christopher Robinson

While some ESOL students arrive at Fall Church with no formal education or school records, school officials are able to assess their English language and literacy proficiency level and place them in the most appropriate of four education levels. Students who only know a few words of English are placed at level one. Students in level two usually have an intermediate understanding of English while those in levels three and four are considered reasonably proficient in speaking and understanding English.

“Many of them have been working from a young age in small villages and rural areas,” Robinson says. “That’s all they know.”

When ELL students struggle with their lessons and are forced to take multiple-choice standardized tests, Robinson says, they get frustrated.

“Some of them talk about dropping out of school, like maybe one of their cousins who now has a job, an apartment and a car,” says Robinson. “It’s tempting for some of them.”