Key Takeaways

- A recent study shows that teachers’ working conditions have declined significantly since the pandemic.

- Key indicators of teacher safety, student disruptiveness, “innovation”, and trust among teachers, parents and administrators are falling.

- “Our findings raise concern about the state of the teaching profession,” the co-authors wrote.

Teaching during the pandemic was hard. Remember that? Navigating entirely new, online learning management systems, while attempting to connect with and inspire and teach students who were sometimes sitting in their closets or McDonald’s parking lots, it was hard, hard, hard.

Today, it’s worse.

“Surprisingly, the pandemic was not a low point,” notes a new University of Missouri study of teacher working conditions from 2016 to 2023.

Indeed, the study shows that teacher working conditions have declined significantly since the pandemic, especially around key indicators of safety, student disruptiveness, and trust among teachers, parents, and administrators.

“Our findings raise concern about the state of the teaching profession,” write the co-authors, Sofia Baker and Cory Koedel, “complementing recent work by Kraft and Lyon, showing that professional prestige and satisfaction among teachers nationally have been declining broadly for over a decade.”

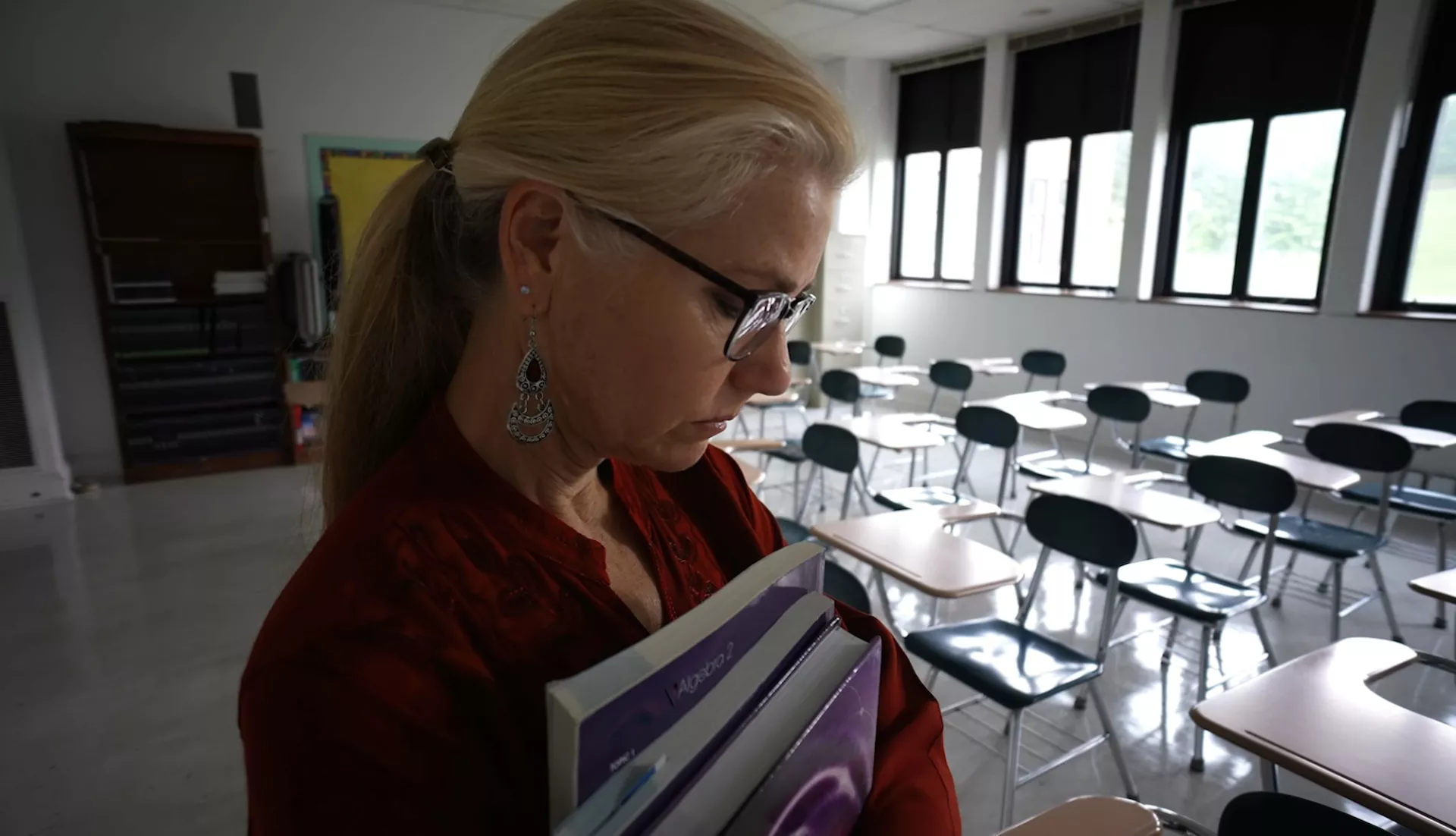

This issue of working conditions is key to the national problem of educator retention, which feeds the crisis in school staffing. While this study focused specifically on teachers, its findings may be applicable to all kinds of educators—everybody from school bus drivers to school psychologists.

“Sometimes staying becomes part of the problem when you become a willing party to your own abuse and degradation and that of your colleagues and students,” a Minnesota teacher told NEA Today. “Sometimes walking away is the only protest lever we have left to pull.”

The Pandemic Wasn’t Rock Bottom

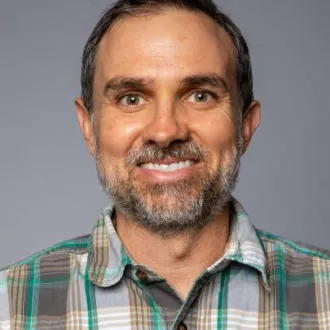

In this new study, Baker and Koedel take a deep dive into the annual “5Essentials Survey in Illinois,” in which almost every teacher in the state—from rural southern Illinois to urban Chicago and the suburbs in between—reflect on “how things are going on the job,” said Koedel.

Their analysis finds that between 2016 and 2023, which span the COVID-19 pandemic, just two of the 20 indicators of teachers’ working conditions improved slightly. (One is “new teacher socialization,” the other reflects parent participation).

The other 18 declined.

“There are a bunch of different indicators turning negatively,” Koedel told Harvard researcher Paul E. Peterson recently, during an episode of Peterson’s podcast, “Education Next.”

“The ones with the biggest declines are things like classroom disruptions, teacher safety, which I personally found a bit startling,” Koedel noted, “and then stuff relating to teacher-student interactions like the quality of student discussions, student responsibility, and dimensions of trust.

“Teachers get asked how is trust between you and parents and the principal, and those things have been trending quite negatively since the pandemic.”

The findings surprised Koedel, a professor of economics and public policy at the University of Missouri, who expected to see the biggest decline in working conditions during the pandemic, he told NEA Today.

“I thought that would be a really terrible time,” he said. “But then working condition got worse—and at a faster rate—in 2023.”

Quote byCory Koedel , Professor of economics, University of Missouri

Classroom Disruptions and Teacher Safety

During the pandemic, one aspect of teachers’ working conditions actually improved quite a lot: it was teacher safety.

“You see that the biggest increase of any working condition measure was during the pandemic [when we see] this big increase in teacher safety, which makes sense: they were working from home,” Koedel said. “Then, after the pandemic, teacher safety declined, more than offsetting the gains during the pandemic.”

The specific working conditions that fell farthest, during or after the pandemic, are:

- The level of classroom disruptions. This indicator had been improving in the years leading up to the pandemic, but it tanked after the pandemic, falling faster than any other indicator between 2021 and 2023.

- Teacher safety. particularly in 2021-2023.

- The quality of student discussions. This indicator has fallen significantly since 2019.

- Innovation. To measure this particular aspect, teachers are asked about their efforts to improve teaching and their ability to try new ideas. This measure improved slightly during the pandemic, but then fell dramatically between 2021 and 2023.

- School commitment. To measure this aspect, teachers are asked whether they look forward to work and whether they would want to work elsewhere. This measure held steady during the pandemic, then also nosedived between 2021 and 2023.

Additionally, all indicators around trust fell after the pandemic. That includes trust between teachers, trust between teachers and parents, and trust between teachers and administrators.

Overall, the rate of the decline was the same at schools with low rates of poverty among students and schools with high rates of poverty—although teachers at wealthier schools report better working conditions overall. Baker and Koedel also found that the rate of decline was worse at schools that stayed online longer during the pandemic, especially on trust measures and on some student-focused measures, like the quality of student discussions and reflective dialogue.

“Utterly Exhausted”

The findings reflect what Peterson hears from teachers, he told Koedel: they love teaching, but the job is getting harder and harder to do. They also match what teachers say on NEA Today discussion boards.

“This isn’t sustainable,” one Tennessee teacher said recently.

“I’d quit if I were in my first 10 years… disrespectful, defiant, and violent children—and no more pension!” said another, from New York.

And, from Colorado: “I still love teaching…it’s a changing society that has left me utterly exhausted… deep down in my soul…deep down in my bones…utterly exhausted.”

So, what’s driving these declines in working conditions? In his podcast, Peterson noted, “I can imagine that working conditions are getting worse because students are more challenging, [with] social and emotional distress obviously taking place.”

The data doesn’t provide the ‘why,’ Koeder said. “Our study doesn’t directly inform that question. We don’t have data into what exactly is causing teachers to report that their working conditions are deteriorating, but the data is certainly consistent with it being more difficult for teachers to manage their classrooms.”

The data around “instructional leadership” and “teacher-principal trust” also is consistent with “problems with administrators,” he noted.

Finding Solutions

These are issues that NEA members have answers to. Through their unions, at the bargaining table or in the halls of statehouses, NEA members are addressing working conditions.

NEA members have won lower class sizes in Washington State, additional duty-free time and time to collaborate with colleagues in Massachusetts, and more funding to hire specialized educators who work on student behavior and mental health issues.

Local and state unions have won greater professional autonomy, too, by claiming a seat at the table around curriculum decisions and other matters.

They've even negotiated for climate control (hello, Columbus!), ensuring that classrooms aren't freezing cold or searingly hot.

And they've partnered with parents and community members to make these changes happen. "We always say that our working conditions are student’s learning conditions," said Portland Association of Teachers President Angela Bonilla, in the run-up to Portland's 2023 teachers' strike, which ended with improvements in planning time, caseload for special educators, climate-controlled classrooms, and more.