Key Takeaways

- Fueled by misinformation and dehumanization, extreme or "affective" polarization is a threat to our democratic values.

- While teachers should always be careful about overstepping boundaries, they should not avoid discussions about controversial political issues in the classroom.

- "Neutrality"in the classroom is counterproductive if it prevents educators from correcting misinformation and calling out toxic, divisive and racist statements by political leaders.

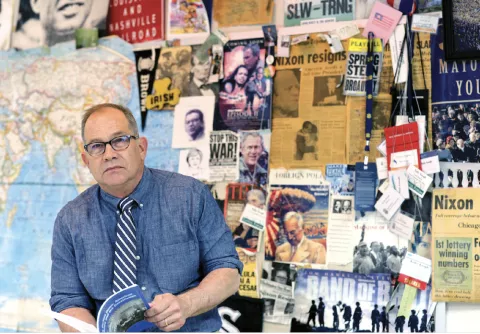

For the first time in his 32-year teaching career, Kelly Keogh found himself standing in front of his social studies class, reminding students that Nazis are, in fact, not good people. Keogh, who teaches AP government and international relations at Normal Community High School in Illinois, was responding to then-President Donald Trump’s shocking comments that the neo-Nazis who marched on Charlottesville, Va., in August 2017, included “some very fine people.”

Obviously, no student in Keogh’s class endorsed Trump’s comments. Keogh’s condemnation was borne out of exasperation and frustration at the toxicity of what now passes as political discourse in the country.

The danger, as Keogh saw it, was the normalization of such rhetoric in our hyper-polarized political climate. There was no “both sides” to the Charlottesville violence, nor was there any legitimate defense for the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Until 2016, Keogh was guarded about expressing his opinions about politicians’ statements, however controversial. But when the rhetoric, particularly over the last five or so years, began to obliterate already blurred standards of civility, decency, and established fact, Keogh shed some of his neutrality.

“I struggled with it at first, but I began to take more of a stand. As an educator and presumably a role model, I couldn’t let this stuff go by without comment,” he recalls.

But many educators still stay far away from discussing political topics or events, either because they fear reprisal or believe it to be inappropriate (or both). But today, “political” subjects could mean just about anything.

Educators should always be mindful of overstepping boundaries by endorsing candidates or specific party positions, says Paula McAvoy, a professor of social studies education at North Carolina State University. But she believes the danger posed by polarization may require teachers to have a more active presence and focus.

“Extreme polarization can lead to an attack on our values,” McAvoy says. “We need to recognize that it’s undermining our democracy, and that’s not something that schools can or should ignore.”

Consumed by Rhetoric

Christine Nold, a sixth-grade social studies teacher at Frederick H. Tuttle Middle School, in South Burlington, Vt., believes that avoiding political issues in her classroom would be an abdication of her responsibility.

“We can’t deny the experiences so many of our students are having in their lives.” she says. “This idea of avoiding what is political means that there is nothing to be done in a classroom. It’s on us to provide the space to discuss these issues.”

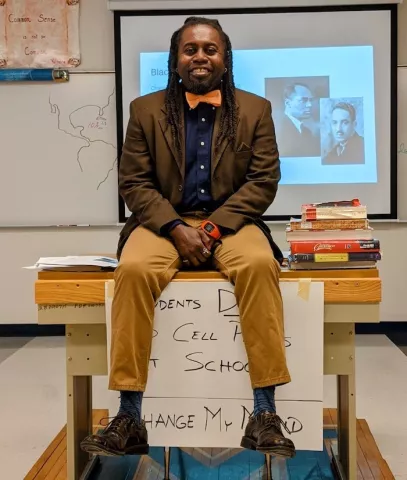

Duane Moore agrees. A government teacher at Hamilton High School, in Ohio, Moore is appalled that in many districts, educators are not allowed to bring up certain topics in class.

“I find that absolutely heretical, because our job is to study that which happens outside the classroom, bring it in the classroom, offer content, and help make sense of it so our students know what is going on when they go back out into the social world.”

Nold was thinking about this responsibility as she watched rioters overrun the U.S. Capitol Building on Jan. 6—some armed with stun guns, pepper spray, and baseball bats. Horrified by what she saw, she tweeted, “Each person knocking down those doors once sat in a classroom.”

The comment immediately sparked a flood of comments. Some accused Nold of blaming educators and public schools for political extremism. Nold was actually calling out what she saw as a missed opportunity. She believes our educational system can do more to prepare students to become citizens: Where is the focus on critical thinking skills? Do we need to change how we teach civics? Are we pushing too much “neutrality” on teachers, even when misinformation, animosity, and even racism pollutes classrooms?

It can be daunting to address and navigate around the toxicity of the public discourse, no question about it. “Students are consumed by the politics of the moment and the overheated rhetoric,” Moore says.

Clearly, today’s politics are plagued by extreme or “affective polarization”—the tendency to view those in another political party as not only wrong or misinformed, but malicious, distrustful, in short, an enemy. “I tell my kids all the time that we are going to have to start talking to each other if we have any hope of getting out of any of these messes we are in,” Moore explains. “Staying neutral or playing it safe as an educator is not going to help.”

Modeling Process, Not Opinions

Moore teaches African American history in addition to government and approaches many issues from a social justice perspective. “The [students] know generally where I stand,” Moore says. “I have a degree of comfort and openness that I bring to the conversation. That helps to develop a rapport with students.”

He adds that it’s key to always having a defensible position, which he insists is not the same as persuading students to subscribe to a particular ideology. When you present a well-reasoned, evidence-based point of view that skews one way or another, Moore believes you are showcasing how to source information. “I’m modeling the process, not the facts,” he says. “I’m highlighting media literacy, reliable sources, coming to an issue and understanding its complexity and nuance.”

“I tell my kids all the time that we are going to have to start talking to each other if we have any hope of getting out of any of these messes we are in. Playing it safe as an educator isn't going to help.” - Duane Moore

Civil discussion, says Maria Jarzabek, is a "skill that is lost in our culture right now." A history teacher in Londonberry, New Hampshire, Jarzabek teaches a current events class where discussions can get a little heated, but never personal.

"I try to develop a climate in my classroom where hopefully students feel comfortable with one another," she says. The first thing she does every semester is help students identify reliable sources of information. "It's not my job to tell my students where I stand, but I will correct misinformation."

Jarzabek says promoting respect for facts and civility in the classroom - especially when discussing issues and events that generate such deception and vitriol outside the classroom - is a challenge.

"I enjoy teaching current events but it takes a lot of preparation. I'm consuming news all the time and it can be a bit overwhelming. But the students love the class, and they think it should be a required course, not just an elective."

Boundaries and Ground Rules

Educators don’t have to be experts on every issue, says Kelly Keogh, but agrees that teachers need to do their homework. “There’s been this downplaying of content knowledge to quite some detriment,” he says. “So preparation on the part of the teacher is critical. Know what you are talking about all the time. You can’t just let students go forward without you having that solid foundation of knowledge.”

When students deliberate over an issue in his classroom, Keogh will have students present arguments in front of the class they don’t agree with and help them find dependable sources of information.

Outside the classroom, students probably haven’t been exposed to many competing viewpoints—at least not those already demonized and ridiculed through the lens of their favorite news sources (or their parents for that matter). “Students want to do well, so they’ll do a good job arguing a position they personally may find otherwise unacceptable,” Keogh says.

He is careful to establish and enforce ground rules around any personal attacks and cut off arguments based on false information or biased and racist stereotypes.

Nold also structures discussions with her sixth graders carefully. Her classes focuses on media literacy and reliable sources without the potential pitfalls of a debate, which could lead to hurtful or dehumanizing comments. “I make it clear that the lines people cross outside my classroom in discussing an issue, such as immigration, are not acceptable inside my classroom,” she says. “I will not hesitate to point out to my students the harm that is done by certain language and the harm that is done by repeating it.”

Without these and other guardrails, Nold believes an educator can’t create the space needed to have constructive, humanizing conversations about any topic.

More Deliberation, Less Debate

Ultimately, for these educators, the goal is to deliberate over an issue, not merely to debate it.

Debate can be healthy and stimulating, especially when facilitated by experienced and first-rate teachers. But debates can go wrong, McAvoy says.

“Student engagement is good, hurt feelings and anger are not,” she adds. “I think we should turn our classroom into places where we can collectively explore how to live together, versus let’s all figure out our views, hold them, defend them,” she explains. “Deliberation is a different type of discussion. Deliberation is about trying to come to a common understanding rather than winning.”

“Extreme polarization can lead to an attack on our values. We need to recognize that it’s undermining our democracy, and that’s not something that schools can or should ignore.” - Paula McAvoy, North Carolina State University

Although moving toward deliberation-based classroom strategies, McAvoy adds, can help curb affective polarization, such a shift doesn’t necessarily make the classroom any less challenging. This is why teachers, colleges, districts, and school leaders have to prioritize professional development, and, perhaps more important, have the trust and confidence in educators to be the professionals they are.

By helping teachers get comfortable with bringing politics into the classroom, Nold says, schools can play an important role in lowering the country’s political temperature. “What’s so great about public schools is that they bring so many students together with various perspectives, so it’s a real opportunity to help them develop a more humanizing approach to viewing the world—and not have them leave my classroom and fall prey to radicalization,” she says.

“If we help them explore these issues responsibly, I think we will see less people go down that path.”

Suggested Further Reading

-

Teaching Across a Political Divide

Harvard Graduate School of Education

-

Civic Online Reasoning institute

Stanford University

-

Project of iCivics

CivXNow

-

Choices Program

Brown University

-

Combat Misinformation and Manipulation

AllSides

-

Media Literacy Resources

Newseum

-

CIRCLE (Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement)

Tufts University