Axel Herrera Ramos, a 19-year-old sophomore at Duke University, remembers the sound of the rain on the metal roof of his childhood home in Honduras. But that’s about all he remembers. Since age 7, he has called the U.S. his home.

Axel Herrera Ramos, a 19-year-old sophomore at Duke University, remembers the sound of the rain on the metal roof of his childhood home in Honduras. But that’s about all he remembers. Since age 7, he has called the U.S. his home.

“Let me put it this way—I can name every U.S. president, but I have no idea who is the president of Honduras,” he said.

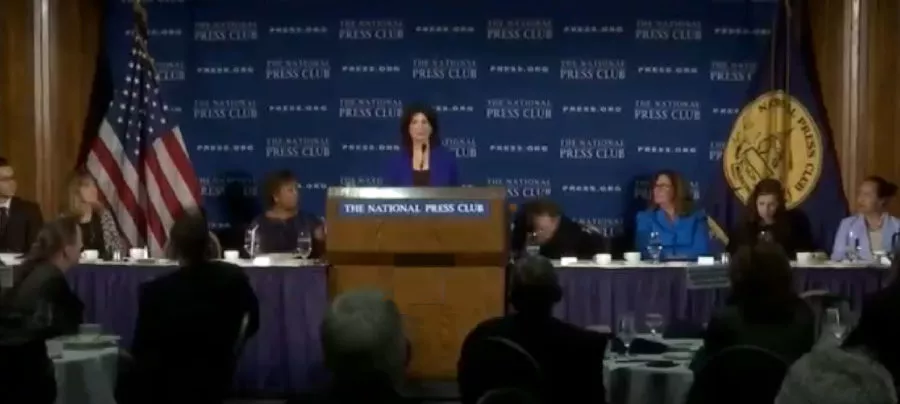

On Friday, just days after President Trump formally announced the end of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), a federal program that has protected from deportation more than 800,000 young people who were brought to the U.S. as children, Ramos accompanied NEA President Lily Eskelsen García to the National Press Club in Washington D.C. Eskelsen García delivered a speech in which she pledged publicly to protect Ramos, his peers, and the hundreds of thousands of other immigrant students, undocumented or not, in U.S. public schools.

“You have our hearts and we will be fighting for you. Whatever it takes,” she said.

DACA, which was implemented in 2012 by President Obama, has worked to protect eligible young people from deportation for two years, subject to renewal, and provides them with a work authorization permit. Its recipients—often called DREAMers—have graduated college to work in U.S. technology, health fields, and public education. Public school teachers in Texas, Florida, Colorado, California and elsewhere are among the nation’s DREAMers.

“DACA is an unqualified success on every level. It’s humane. It’s just. And it’s pumping millions of dollars into our economy,” said Eskelsen García. “These are our students and we want to comfort them, but it’s hard to tell them the president can’t hurt them. They know the truth…

“But they will have to come through us to get to those students.”

Sign the NEA pledge to protect DREAMers.

The Best Public Schools

Earlier this year, Eskelsen García sent a letter to U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, in response to DeVos’ invitation to meet. Eskelsen García’s letter asked her three questions: Will you hold privately managed voucher and charter schools to the same standards of financial transparency as public schools? Will you privatize federal programs, like special education? Will you protect all students from discrimination—our students of color, our immigrant students, etc?

Axel Herrera Ramos at the National Press Club on September 8.

Axel Herrera Ramos at the National Press Club on September 8.

DeVos has never answered—not explicitly. But the administration’s abandonment of 800,000 young people is a kind of answer. Its new multi-million dollar federal voucher program also is an answer. “Her actions scream,” Eskelsen García told the National Press Club on Friday.

These are the wrong answers for America public schools, she added. The right answer is to make sure every public school is as good as the best public school—and this is possible. “Some of the best schools on the planet are among American public schools,” Eskelsen Garcia said.

But schools aren’t great because they have fantastic test prep programs. Or because they’re in cutthroat competition with for-profit charter schools, she said. These schools are great because they have excellent educators, who have “the collaborative authority to make instruction decisions for their students. They have technology that works and books in their libraries, and after-school programs and field trips and choirs and a debate team.”

Something that actually works to improve schools, Eskelsen García noted, is to treat students as whole people with complex needs, and involve their families and communities in their schools. Across the nation, community schools are feeding students, providing them—and their parents—with health care, even teaming up with local orchestras to provide music instruction.

From Honduras to Duke University

“I am frightened that these people who don’t know what they’re talking about will destroy our nation’s brightest crown jewels—like public education,” said Eskelsen García.

But she is also hopeful—and her hope includes the promise that Congress may actually legislate a compassionate, just solution for the 800,000 DREAMers in the U.S.

For his part, Ramos, who is studying economics and public policy at Duke, one of the premier private universities in the nation, also has promised to stay and fight for that solution. “Personally, I’m not going anywhere. The magnitude of having to transition from here to there is incomprehensible,” he said. “What’s in it for us, for students like me, is everything.”

Ramos also thinks about his mother, who crossed the border more than a decade ago, alone with her 7-year-old son, 3-year-old daughter, and a 12-year-old cousin. She has worked ever since, investing in her dreams for her children. “I see the efforts of my mother. I see the efforts of my teachers and counselors, and all the people who told me I could find a way.

“Being a DREAMER…for me, it’s about working to achieve something great.”