“I got a new sewing machine for my 21st birthday. I know, even my mom was like, ‘Madison, you’re too much!’” says Aspiring Educator Madison Woosley. “But I love to quilt. It’s my way to chill out.”

Not only is Woosley a full-time elementary education major at Morehead State University and president of Morehead’s Kentucky Education Association chapter, she’s also a Student Government Association rep and involved in Christian ministry. Three afternoons a week, she tutors. The other two days, she runs an after-school elementary education program—an experience she is documenting and studying as an undergraduate research fellow.

It doesn’t leave a lot of time to stitch and baste. “My days are very full,” says Woosley, with a laugh.

As Woosley and other Aspiring Educators look ahead—beyond student teaching and graduation—this isn’t going to change. The crunch for time will be a constant throughout their careers. Indeed, 84 percent of teachers say they don’t have enough time in their day to get everything done, according to a 2024 Pew Research report.

That’s why it’s important for NEA Aspiring Educators to learn time-management skills now. Prioritizing work, setting boundaries, learning to say no, and making time for your own well-being are key skills that can be practiced and learned. Future educators also need to know how their unions can help.

Running Out of Time

In a recent national survey, K–12 teachers answered questions about their workloads. The most cited reason they can't get everything done? Ninety-eight percent said they simply have too much work. Other reasons include spending time outside of class helping students and covering for other educators.

98%

65%

72%

51%

The time crunch is a growing issue educators say. As students’ needs are increasing, parents’ demands are growing, and dictates on teachers’ time are multiplying. These burdens often lead to burnout, which causes educators to quit, which feeds the national educator shortage, which, in turn, makes more work for the remaining staff.

Who suffers the consequences when educators don’t have enough time? Students do! “Probably the biggest thing is students get less personalized feedback,” says New Mexico teacher Natalia Fierro, who, after teaching language arts for 20 years, recently switched to a media elective. “We probably also give fewer innovative assignments. There’s not time to plan them and get the resources for them.”

Of course, educators bear some of the brunt of the time crunch, too. A large majority (74%) find their jobs to be overwhelming. And although stress is common across the profession, it is more pervasive in elementary grades, the survey shows. It is also very common among special educators and specialized personnel, says Christina Rojas, a speech-language pathologist in Lancaster, Penn.

“It’s not about making our jobs easier,” she says. “The focus is students. How can we make this job manageable to provide better services to students?”

Solutions are possible, say NEA members, especially when educators work through their unions.

“How do we keep teachers in the classroom? How do we keep them from … burning out?” asks middle school teacher Michael Sniezak, president of Washington’s Eatonville Education Association. “The solution is to make it so teachers don’t feel spent beyond [reason].”

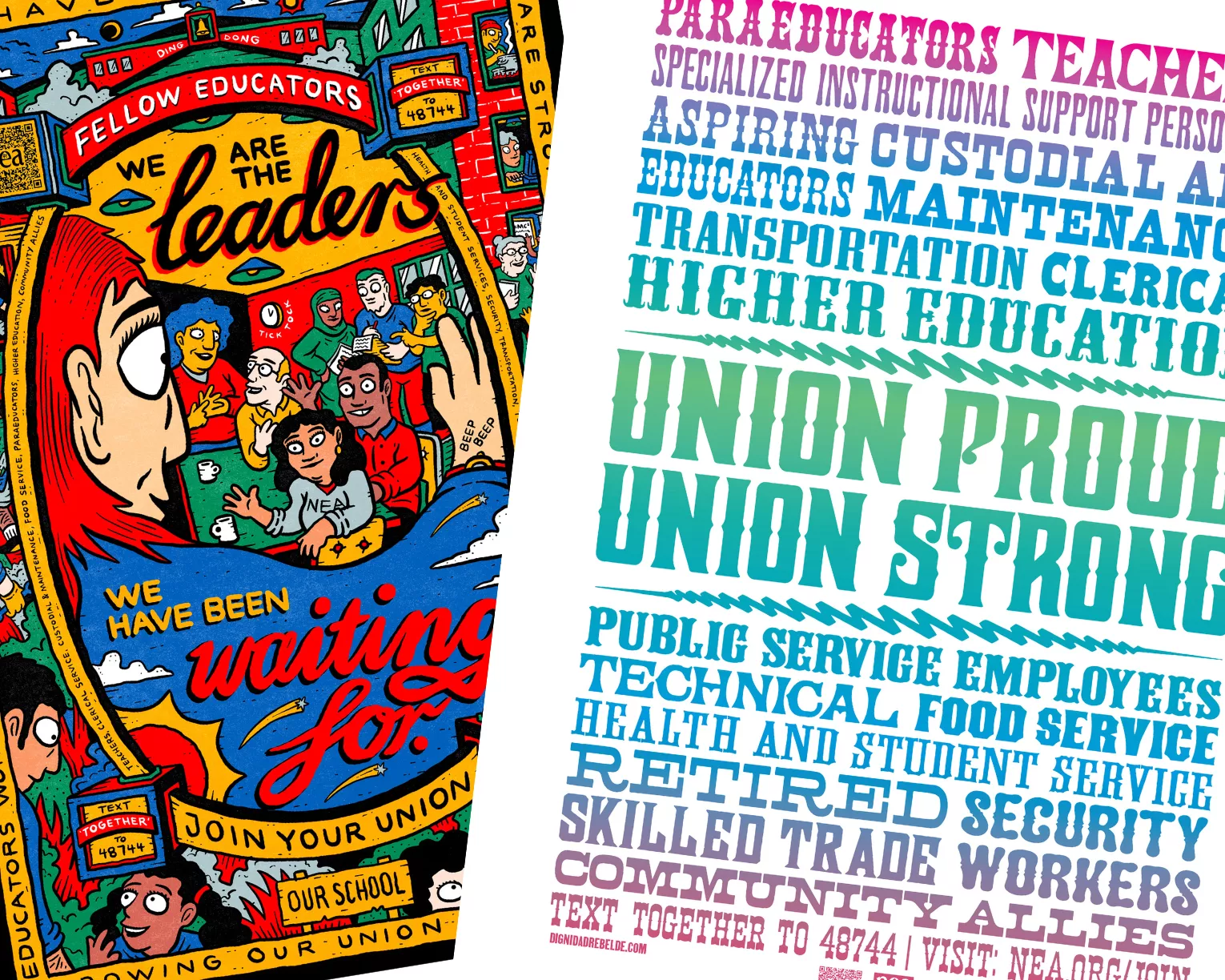

3 Things You Can Do Through your Union

You Can Make a Difference!

While local and state unions tackle workload, class sizes, planning time, and other issues at the bargaining table and in statehouses, Aspiring Educators can help themselves, too.

Fortunately, Aspiring Educators already know a lot about time management! About 4 in 10 college students also work part-time (and 74% of part-time students), so it’s not unusual for students to learn how to juggle.

Jonathan Oyaga is an Aspiring Educator in Los Angeles, where he recently graduated from University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Today, he’s serving as president of the California Teachers Association Aspiring Educators and on the NEA Board of Directors, as well as working as a research associate at the UCLA Center for Community Schooling and a transfer specialist at Pasadena City College.

He and Woosley have advice for their colleagues.

5 Things You Can Do For Yourself