When Cheryl Cochran started teaching in Tennessee’s Hardin County School District, in the mid-1980s, it nearly broke her heart to know that some of her high school students had to go hungry.

“Back then, on Mondays, students on free or reduced-price meals picked up an envelope with green tickets in it,” Cochran explains. But if something happened to those tickets—like, “My mom washed my jeans and the tickets were in the pocket!”—they might have to go without lunch Tuesday through Friday, she adds.

Even when students did keep hold of their tickets, they had to use them in front of peers, who would then know that those families had financial struggles.

But these problems vanished once the school district adopted the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, says Cochran, who has served as the district’s school nutrition program director for 29 years. The provision allowed the district to offer free meals to all students, and the positive effects were immediate: No more meal debt, no more embarrassment, and no more students distracted by hunger pangs.

“Now every student in the district can have a no-cost breakfast and lunch at school, so all students are on a level playing field,” she explains.

How much is a child’s health worth?

Research shows that CEP increases school meal participation, boosts school attendance and test scores, and reduces disciplinary problems. Despite CEP’s popularity and proven benefits, the program could be targeted for spending cuts. In fact, the Project 2025 policy document—concocted by a conservative think tank to serve as a blueprint for the second Trump administration—calls for CEP to be eliminated entirely.

Why? Because to some out-of-touch politicians, easing child hunger is simply not worth the price tag.

“If Congress refuses to fund universal school meals, expanding Community Eligibility is the next best way to help schools win the battle against student hunger,” says NEA’s Angelica Castañon, an expert in student learning conditions.

“NEA continues to advocate for CEP, and all the federal programs that help students get the healthy meals they need.”

How community eligibility works

CEP is available to schools in which at leat 25 percent of students comes from low-income families. Nearly 60 percent of the 3,275 students in rural Hardin County are considered low-income, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

CEP helps educators, too. Not only are well-nourished students more focused in class, but educators are no longer paying for students’ meals out of their pockets.

Cochran can’t stomach the thought that the federal government could roll back or eliminate the program.

“We live in a great, prosperous country, and it’s the right thing to make sure all students are fed,” Cochran says. “We provide transportation and textbooks—providing school meals is just as important.”

We can curb student hunger!

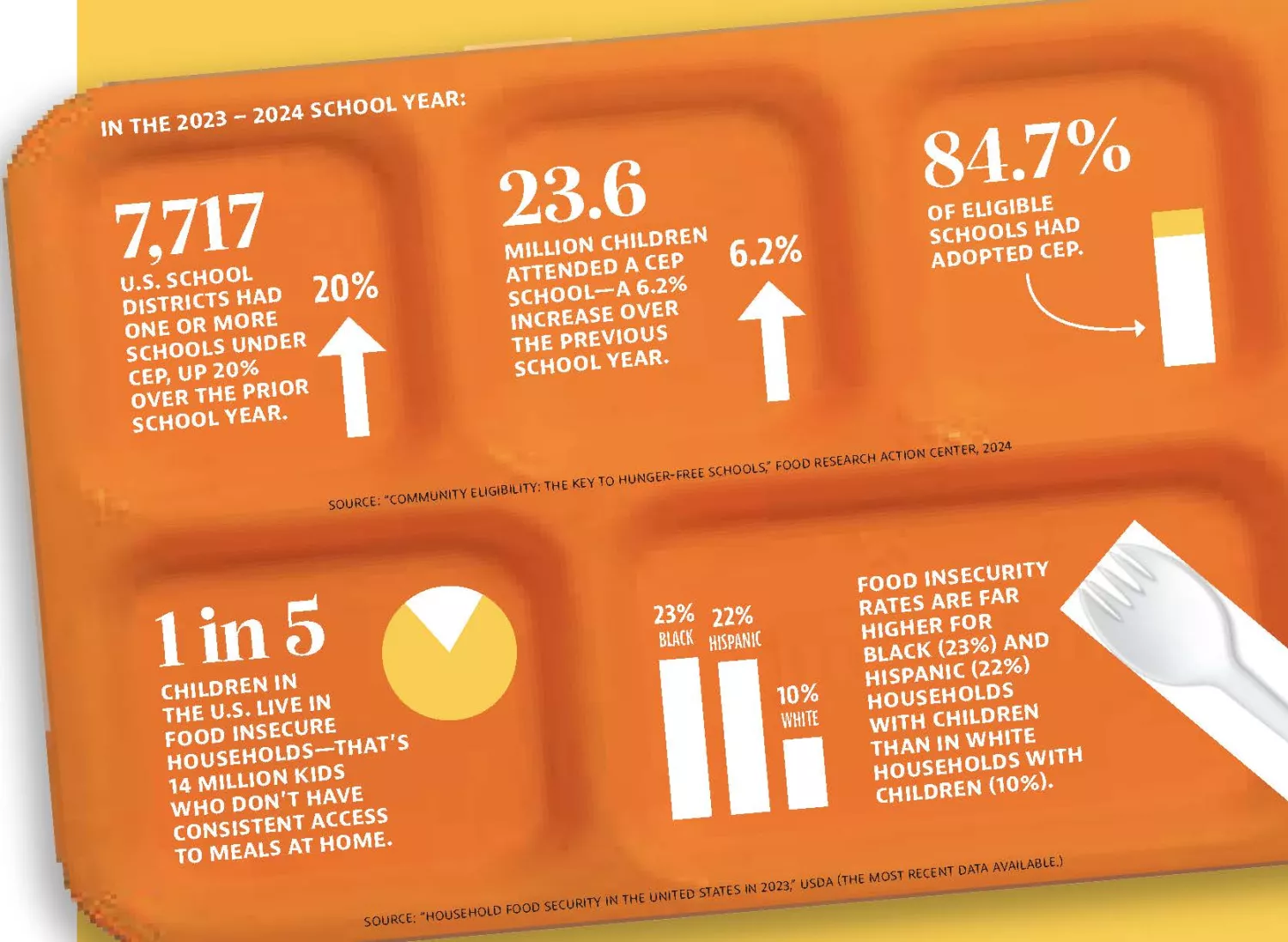

The number of schools adopting the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act surged during the 2023 – 2024 school year. Why? Because Congress let the national universal school meals program—funded by the Biden administration’s pandemic recovery plan—expire in 2022, which resulted in a spike in hungry students.