Key Takeaways

- 2024 marks the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Cleveland Board of Education v. LaFleur decision, a landmark case for the rights of pregnant women in the workplace.

- The NEA lent financial and legal support to Jo Carol LaFleur, the plaintiff in the case.

- Today, educators and their unions are demanding (and winning) paid family leave in contract bargaining.

Fifty years ago, Jo Carol LaFleur was teaching at Lakewood High School in the Cleveland suburbs when she heard the Supreme Court had decided her case. “A student came to my class and whispered to me that I had a phone call from a radio station,” she recalled in a 2006 Georgetown Journal of Gender and the Law piece.

After hurrying out to the teacher’s workroom to call her lawyer, LaFleur “leaped back” to her classroom, doing “one grand jeté after another” in the hallway. Entering her classroom, she exclaimed to her students, “We won, we won, we won!” and the students began cheering.

The win? A 7-2 victory in the Supreme Court in 1974, striking down the common requirement of the time that pregnant teachers leave their classrooms.

LaFleur’s Supreme Court victory was a turning point for women’s rights in their workplaces. Decades later, it serves as a building block for new family leave policies, recently won at the bargaining table and in state legislatures. A common thread throughout these years? The power of NEA’s representation.

“One Teacher’s Fight For All”

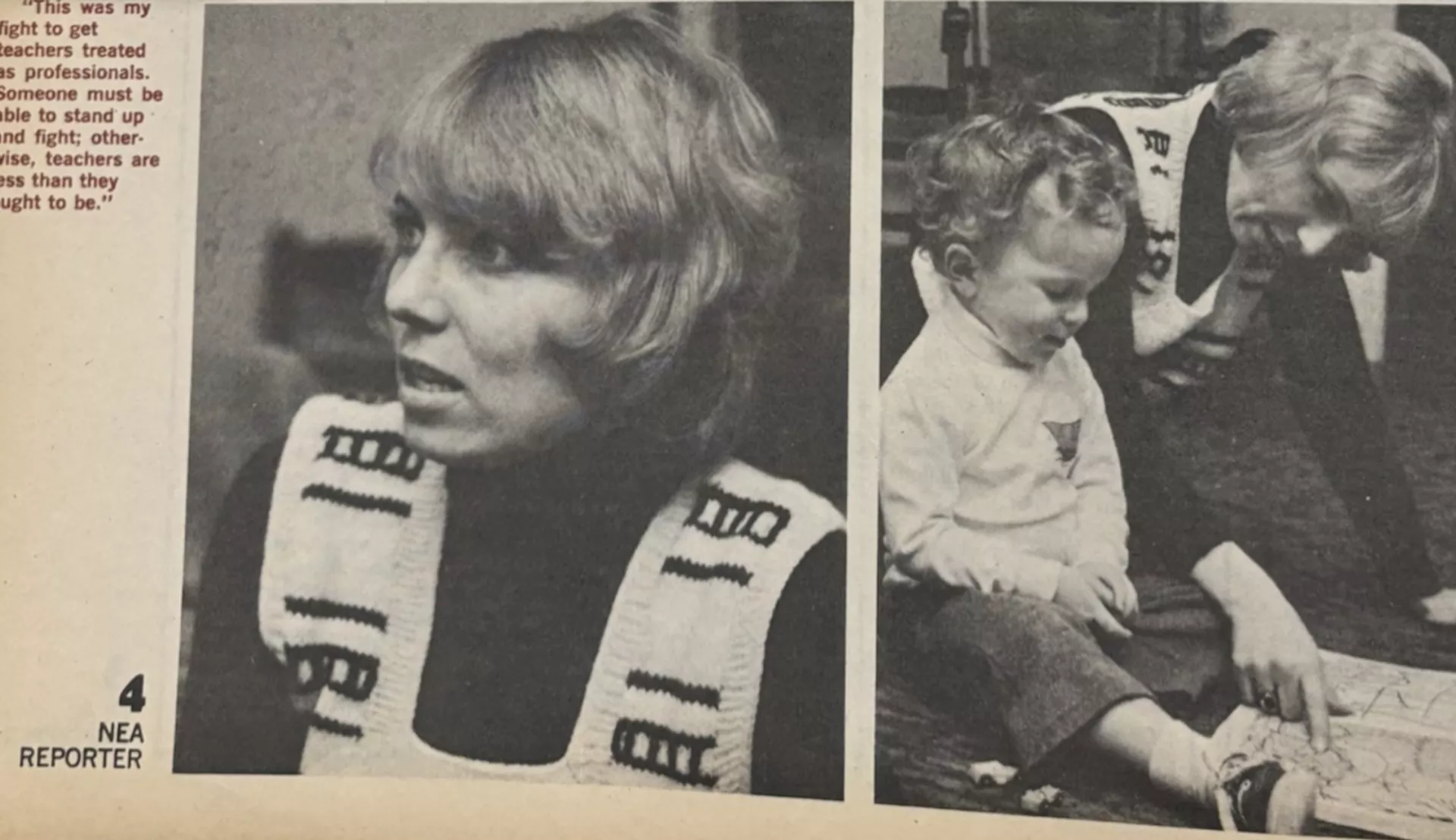

After LaFleur’s victory at the Supreme Court, the NEA Reporter – the precursor to NEA Today – published a feature story on her entitled “One Teacher’s Fight For All.”

“La Fleur discovered before Christmas 1970 that she was two months pregnant,” the Reporter piece begins. Yet, when she shared the exciting news with her principal, he told LaFleur she must “abide by policies in the teacher handbook” that forced pregnant teachers to take unpaid leave after the fourth month of their pregnancies, “despite the fact that I never saw a copy and was unaware of the forced unpaid leave rule,’” she said.

In her 2006 law journal article, LaFleur described her response: “Alternately angry and incredulous, I complained that it was not fair or right, that I did not want to leave, and I would not fill out any request for leave papers.”

Today, the woman at the center of the case, Jo Carol Nesset-Sale, formerly LaFleur, hasn’t lost any righteous outrage. “You just have to stand up to wrong-headedness or wrong-headedness wins,” she explained in a recent interview with NEA Today, five decades later. “I just didn’t want to be someone who didn’t try to stand against ignorance and sexism and discrimination. I just couldn’t bear it that I didn’t do everything I could.”

Nesset-Sale's anger was not only about how she was being treated. She was deeply concerned, too, about the impact of her mid-year departure on her students, a group of 25 seventh-grade girls, all of them Black, grouped together because they were at high risk of dropping out of school. Throughout the year, the girls had “tested and challenged her,” but she had gained their trust. The idea of leaving in the middle of the year? Nesset-Sale couldn’t think of anything worse for her students.

“These men were making these awful decisions, stereotypical decisions in the worst sort that [pregnant teachers] weren’t capable of teaching, and our bodies, we couldn’t stand erect anymore, our center of gravity would be so off that I would be tilting over.”

“I reminded [the principal] that my students had already lost one teacher that school year, and it was not in their best interest to have to lose a second one, especially when there was no reason for it,” Nesset-Sale later wrote. The principal responded coldly: “He gave me a copy of the teacher’s manual and a maternity leave form. The meeting ended.”

Nesset-Sale appealed to her Cleveland Federation of Teachers building representative. Unfortunately, he wasn’t supportive, she says today: “The local [union] representative in my building, a man, of course, belittled it.” She recalls today that he told her, “‘Just go home, have the baby.’”

Between the principal and her building representative, reflects Nesset-Sale, “These men were making these awful decisions, stereotypical decisions in the worst sort that [pregnant teachers] weren’t capable of teaching, and our bodies, we couldn’t stand erect anymore, our center of gravity would be so off that I would be tilting over.”

Undaunted, Nesset-Sale called the library of the Cleveland Plain-Dealer newspaper and asked for the name of a women’s liberation group. This led her to Jane Picker, a lawyer who took her case pro bono on behalf of the Women’s Law Fund, Inc.

Initially, Picker and Nesset-Sale drew a conservative 73-year-old federal district court judge. “To no one’s surprise, but to my great dismay,” Nesset-Sale later wrote, the judge ruled against her in May 1971 and upheld the Cleveland school district’s regulation “in its entirety.”

NEA Gets Involved

Despite the fact she wasn’t an NEA member (Cleveland's union was part of AFT), the NEA jumped in to support Nesset-Sale’s appeal. “Although NEA does not usually support nonmembers,” explained the NEA Reporter back in 1974, “the Association entered both [Nesset-Sale and another teacher, Susan Cohen’s] cases because of their nationwide implications for teachers.” The NEA invested $25,000 in Nesset-Sale’s case (nearly $170,000 in inflation-adjusted dollars) and filed amicus briefs on her behalf.

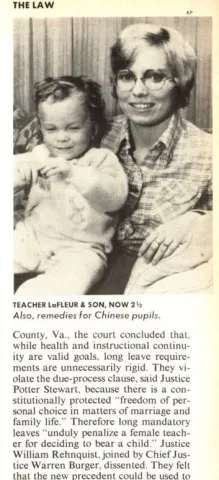

While the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Nesset-Sale, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals did not. The U.S. Supreme Court took up the case to resolve the dueling circuit court opinions. It was at this point, Nesset-Sale says today, that she began to understand that her case was “kind of a big deal.” In February 1974, Time Magazine ran a picture of her, “and you don't get your picture in Time magazine if you don’t have a little something going for you,” she laughs.

Ultimately, legal and financial support from organizations including the NEA and the ACLU’s Women's Rights Project (headed by a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg) helped pave the way for Nesset-Sale's Supreme Court victory—and inspired Nesset-Sale to become a lawyer herself.

Soon after she won her case, Nesset-Sale was attending an evening art class when, according to The NEA Reporter, “A teacher there expressed delight that teachers no longer have to resign at a specified time early in their pregnancy because ‘some teachers’ won a Supreme Court case.” “‘I didn’t tell [the teacher] it was me,’” Nesset-Sale said, grinning, “but I just beamed on the inside.”

Following in Nesset-Sale’s Footsteps

The struggle Nesset-Sale started in the 1970s continues in present-day efforts to achieve paid family leave, as too many parents are still unable to take the time they need to care for their new children.

Columbus Education Association (CEA) member Annelise Taggart is among the educators carrying on Nesset-Sale's fight. Taggart, an art teacher, was part of the CEA bargaining team in 2022, and a major champion for including paid family leave in the union’s next contract.

“We need this,” she would say, at CEA town halls and at the bargaining table.

CEA eventually went on strike for three days before agreeing to a new contract that included paid family leave for the first time. Columbus teachers now use their sick bank for their first ten days after the birth of their child. After this, the district covers 20 additional paid days for a total of six weeks of paid leave. (Non-birthing parents get three weeks, instead of six).

Taggart had a personal reason to be excited about the new contract: she was 10 weeks pregnant. “When we finally came to an agreement,” she recalls, “it was 3 a.m. One of my teammates turned to me and said, ‘Oh, so now you can start working on having another kid.’” Taggart responded: “‘Well, actually, I'm going to be one of the first people to be able to utilize our paid family leave because, surprise! I'm pregnant.’”

After the birth of her daughter, Taggart was especially grateful for the new contract because she experienced postpartum anxiety. “Realizing [that] I have this paid family leave that we won in our contract and not having to have that additional stress when I was already having all kinds of emotional, mental stuff that I was working through as I was newly postpartum – that was really, really wonderful,” she explains.

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

NEA Wins Paid Family Leave Across the Country

- In the contract ratified by the Malden (Mass.) Education Association in the fall of 2022, teachers get six weeks of paid leave after the birth or adoption of a child. They can also use six more weeks of accrued sick leave, for a total of 12 weeks.

- In the spring of 2023, The South Carolina Education Association (The SCEA) members wrote emails, made phone calls, and met with state legislators urging them to pass paid family leave legislation for school employees. SCEA’s advocacy paid off – making South Carolina the first Southeastern state to pass a law providing every school employee with six weeks of paid leave following the birth or adoption of a child.

- Education Minnesota was a key member of “Minnesotans for Paid Family and Medical Leave,” a coalition of health, faith, labor, business and community organizations who successfully fought for Minnesota to establish paid family leave at the state level. Minnesota’s paid family leave legislation, signed into law by Gov. Tim Walz in May of 2023, provides for 12 weeks of paid leave for all Minnesota workers after a qualifying event, such as the birth or adoption of a child, or caregiving for a sick family member.