Key Takeaways

- According to a new survey from the American Psychological Association, one-third of teachers report that they experienced at least one incident of verbal harassment or threat of violence from students during the pandemic.

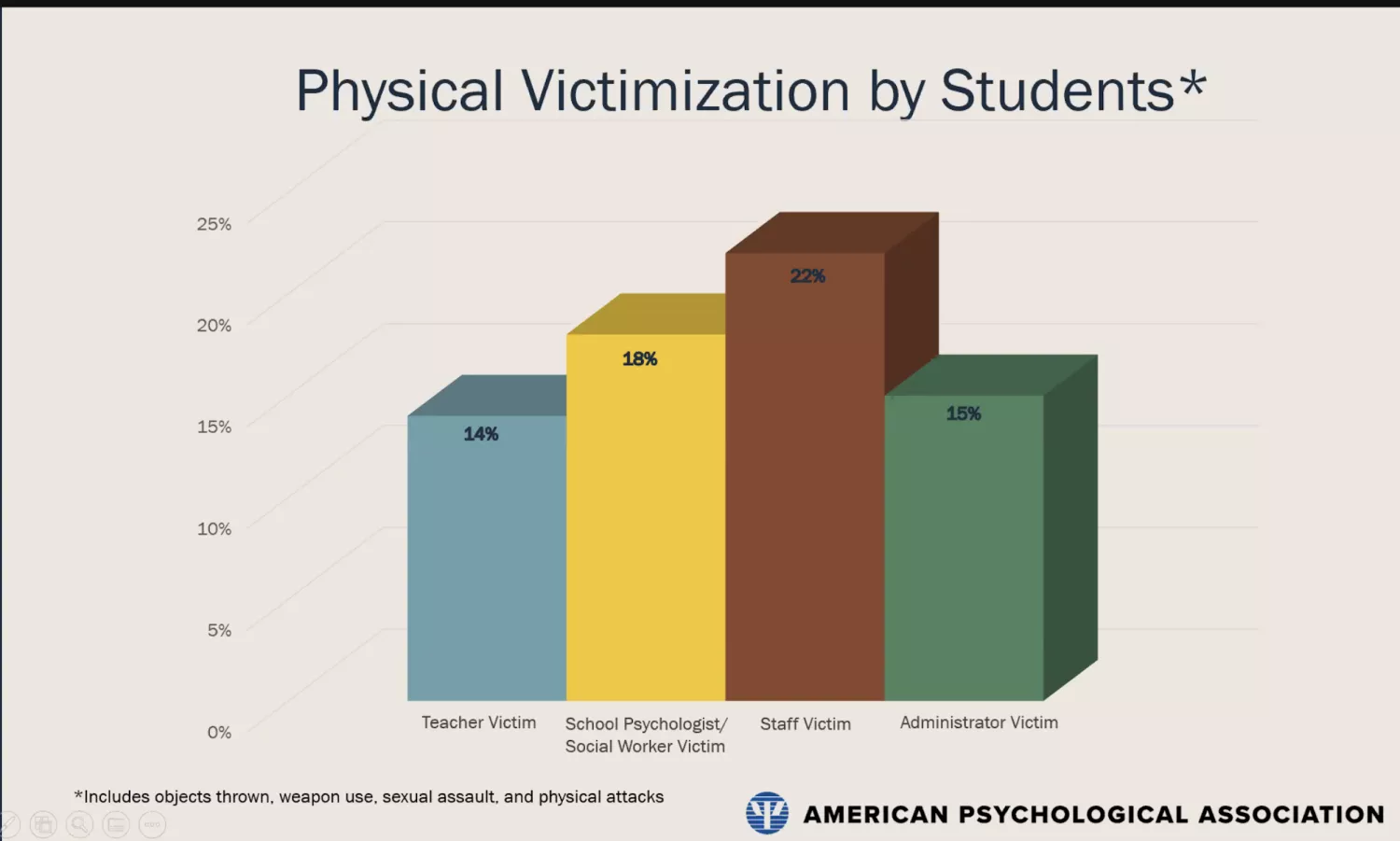

- At least 18% of school psychologists and social workers, 15% of school administrators, and 22% of other school staff reported at least one violent incident by a student.

- The survey is another wake-up call, said NEA President Becky Pringle, for school leaders and lawmakers to address the extreme challenges that are forcing too many educators to leave the profession.

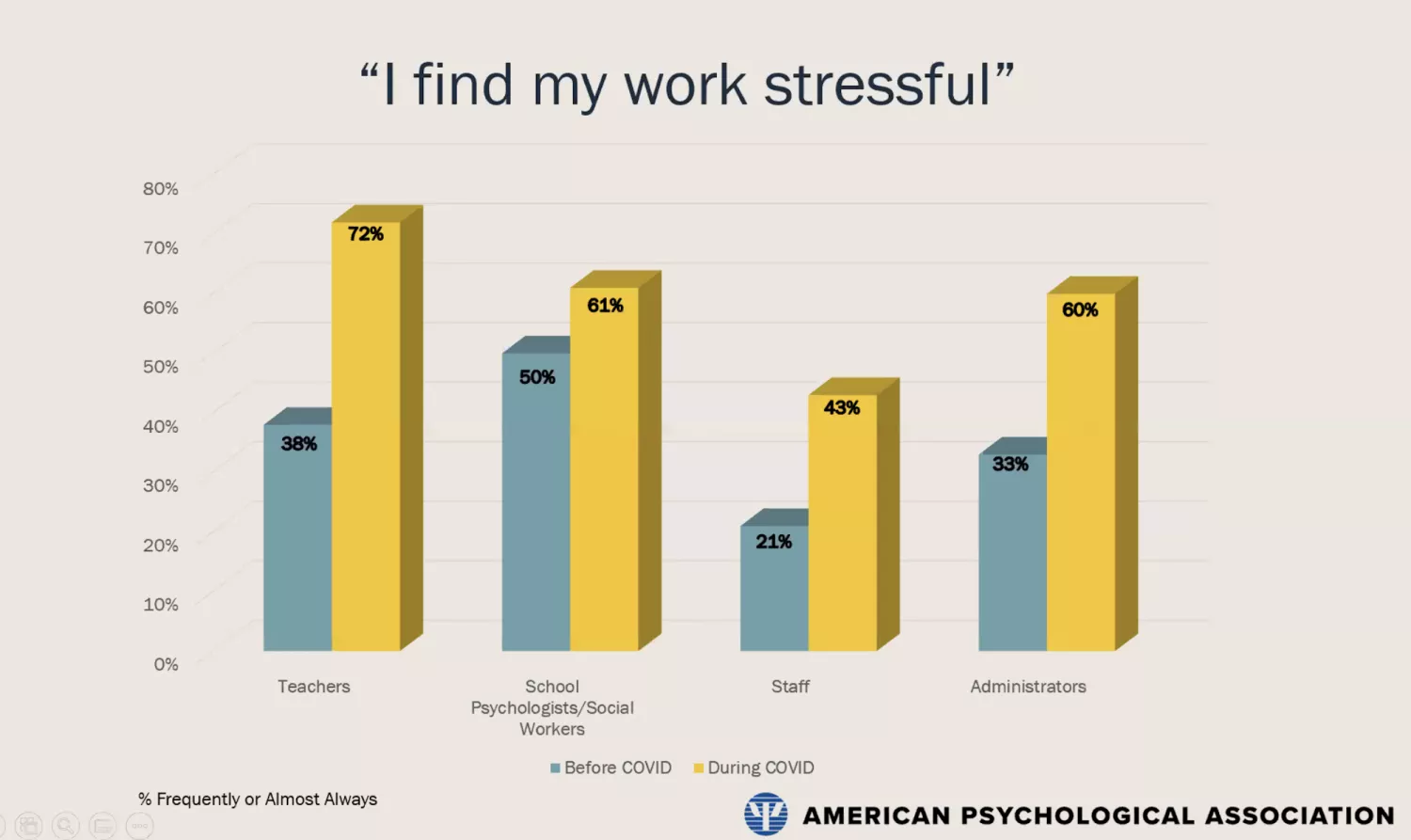

As districts across the nation face a potential exodus of educators over the next few years, the focus on reversing this crippling trend has often been on the need for higher pay, manageable workloads, and generally fostering greater respect for the profession. However, a new study by the American Psychological Association (APA) highlights another longstanding concern: educators’ working conditions, including their physical safety and mental health needs.

From March 2020 to June 2021, the APA surveyed nearly 15,000 pre-k-12 teachers administrators, school staff, and counselors about their experiences with physical threats and attacks from students and parents. The results are disturbing. Rates of violence and aggression against school personnel have been high despite most schools being remote.

One-third of surveyed teachers reported they experienced at least one incident of verbal and/or threatening violence from students (e.g., verbal threats, cyber bullying, intimidation, sexual harassment) and 29% reported at least one incident from a parent of a student. Fourteen percent of teachers said they had been victims of physical violence from students.

Almost half of all teachers reported they desire or plan to quit or transfer their jobs due to concerns about school climate and school safety.

It was school staff (paraprofessionals, school counselors, instructional aides, school resource officers), however, who reported the highest rates of student physical violence. Eighteen percent of school psychologists and social workers, 15% of school administrators, and 22% of other school staff reported at least one violent incident by a student during the pandemic.

Many of the respondents described the violence they face as "on-going and pervasive," according to the APA study.

“Violence against educators is a public health problem," said Susan Dvorak McMahon, PhD, of DePaul University, and chair of the APA Task Force on Violence Against Educators and School Personnel. "We need comprehensive, research-based solutions. Current and future decisions to leave the field of education affect the quality of our schools and the next generations of learners, teachers, and school leaders in the nation."

‘They See the Blood — And They Walk Away’

Since the earliest stages of the COVID pandemic, the nation's school counselors and psychologists were sounding the alarm that the grief and isolation endured by students was taking a severe toll, one that would follow them as schools began to open back up for in-person learning. Addressing student trauma, educators warned, should not be shrugged off as schools focused on getting students back-on-track academically.

The heartbreaking findings in the APA survey, said NEA President Becky Pringle, highlight the urgency to address the funding and staffing crises that have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

"While the sources and motivations behind violence in schools vary greatly, the solutions are clear as day—more staff, more training, and more attention to mental health needs," Pringle said. "And yet, schools are not given the funding needed to hire, train, and retain necessary staff at their schools like counselors and social workers."

It was this lack of resources that compelled special education teacher Tonya Shonkwiler to make the agonizing decision to move to a general education classroom after a student punched her in the face. Shonkwiler, who teaches in Bozeman, Montana, described her experience at the APA briefing on Thursday.

"As I struggled to follow our plan and support this student, my face and clothing covered in blood," Shonkwiler recalled, "an administrator was walking down the hallway and asked me if everything was okay. I said yes. And that was it — the administrator walked away."

The administrator wasn't being callous or unsympathetic, Shonkwiler, a member of the Montana Federation of Public Employees and NEA, believes. The school simply did not have the resources to support her and make staff feel safer at school.

"I didn’t quit because of the overwhelming obstacles or even aggression from students," she said. "I left because my administrators didn’t have the resources and elected officials failed to give us the funding my students and my team needed to keep us all safe. They see the blood — they see the struggles — and they walk away."

Tracey Cooper, a school bus operator in Orange County, Florida, and a member of the Florida Education Association, reported on how the dwindling training opportunities in her district is leaving too many inexperienced drivers without the necessary tools to confront and mitigate incidents of violence and harassment. A few months ago, a parent confronted Cooper and threatened to have her fired for enforcing a mask mandate on her bus, and she has had to defuse potentially violent confrontations instigated by students.

“I love my job,” Cooper said. “I go out of my way to support my students and encourage positive behavior on the bus. But because of deteriorating working conditions, low pay, and physical threats and violence, fewer and fewer experienced drivers are sticking around.”

Supports for Students and Educators

In response to their findings, the APA Task Force recommends schools and districts focus on policies and practices that address student mental health, enhance student engagement, channel more resources into public education, and increase educator involvement in decision-making.

“What was interesting about the survey in asking about what works,” said Andrew Martinez of the Center for Court Innovation in New York City, “was that educators were not asking for zero tolerance. They weren't saying 'lets's suspend these kids.' Instead, they talked about preventative strategies that are built around relationships — restorative justice and trauma-informed practices and programs.”

Over the course of the pandemic, the importance of social and emotional learning (SEL) has moved front and center in school districts across the country.

“I didn’t quit because of the overwhelming obstacles or even aggression from students. I left because my administrators didn’t have the resources and elected officials failed to give us the funding my students and my team needed to keep us all safe.” —special education teacher Tonya Shonkwiler

The emergence of SEL and other trauma-informed practices is an encouraging development, said Dorothy Espelage of the University of North Carolina, but school leaders must look to evidence-based programs to improve school safety and climate. Some programs, while well-intentioned, she cautioned, are ineffective and can actually harm Black and Brown students.

“So we can do SEL but it has to be transformative, it has to be equity-based, and it has to be sustainable,” Espelage said. “That will take resources and funding — and the voice of every member of the school community, including parents.”

SEL and mental health supports are not just for students. "They're also for the educators who are continuing to experience trauma every day as they go to school," said Espelage.

Teachers and other school staff across the country have long been exasperated at being underpaid and undervalued, working without the resources, support and respect they and their students desperately need. Coming to a workplace every morning - whether it's the classroom, cafeteria, or school bus - that also threatens their physical safety will only push them closer toward the exits, exacerbating staff shortages across the country.

"This crisis of violence should unite educators, students, families, and politicians around the common goal of ensuring that our public schools are the safest, healthiest, and most just places in our communities," says Pringle. "We need to address the mental health needs of students and educators, as well as school staff shortages – both of which undermine the learning and growth of our students and the safety of our educators.”

Suggested Further Reading

-

Emergency Mental Health Support

SAMHSA

-

School Crisis Guide

National Education Association

-

School Health

American Academy of Pediatrics

-

Gun Safety and Injury Prevention

American Academy of Pediatrics

-

Trauma-Informed Care

American Academy of Pediatrics

-

Supporting Mental Health in Schools

American Academy of Pediatrics

-

School Safety

National Center for Safe Supportive Learning Environments

-

Guidance at a Glance

National Association of School Psychologists

-

Preventing School Violence

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention