Key Takeaways

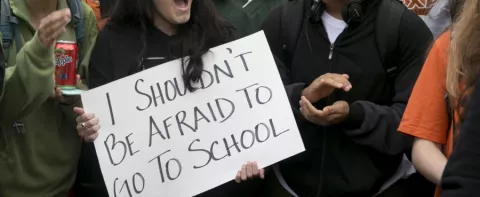

- An unprecedented spike in school shootings has shattered communities and left students and educators nationwide living in a state of heightened anxiety.

- There are proven ways to reduce gun violence in our communities—but most require the political will to make our schools and neighborhoods safer.

- Educators are speaking out to demand change through their unions and national gun safety organizations.

72

357,000

The Day It Happened

On Nov. 30, 2021, Michigan high school teacher Melissa Gibbons became part of a group she never wanted to join: school shooting survivors.

Gibbons was on hall duty at Oxford High School that afternoon when she heard gunshots and saw students running around the corner toward her. Every educator’s nightmare had just become her reality.

After getting the students out of the hall, she put her room on lockdown.

Her twin daughters were also in the building, and their classroom was in the direction where the shots rang out. Gibbons was thankful that she could text with them and with her husband Jim Gibbons—a teacher at the same high school and president of the Oxford Education Association—who was home sick, along with their younger daughter.

“I just tried to focus on keeping my 35 students calm and doing what we had to do,” Gibbons recalls. “It wasn’t until I got home later that night, when all three of my kids were home safe and sound, that I completely went into mom mode and broke down.”

Four students were killed. Six more students and an educator were injured. The community was shattered.

Not long after the shooting, Gibbons shared her story with the Michigan Education Association (MEA). But mostly, she wanted to focus on teaching, parenting, and healing.

Like thousands of other educators across the country, however, she would soon feel compelled to raise her voice to demand change.

A Turning Point

On May 24, 2022, another massacre: 19 students and 2 educators were killed, and 17 others were injured by a gunman at Robb Elementary School, in Uvalde, Texas. The fresh anger Gibbons felt—that school shootings just keep happening—moved her to share her story more widely. When NEA asked, she traveled to Washington, D.C., along with other educators who are school shooting survivors, joining the March for Our Lives in June 2022.

“I don’t have all the answers, but what we’re doing now is not the right answer,” said Gibbons at the time. Today, she is still speaking out on behalf of her students. “We don’t make the laws, but we can have a voice.”

Across the country, educators are using that voice, working through their unions to negotiate safer conditions; support “gun-sense” candidates, who are committed to passing gun safety legislation; and hold elected leaders accountable for their actions—or inaction, as the case may be.

That’s exactly what educators should do, says Rebecca Woodard, an associate professor of curriculum and instruction at the University of Illinois Chicago. She believes that educators have a unique ability to galvanize support for changes that actually work to reduce gun violence.

“Educators can and should organize and collectively raise their voices, alongside outraged parents and youth, to demand gun safety legislation and comprehensive school safety policies,” Woodard says.

There isn’t one thing that will solve the epidemic of gun violence. It will take passing evidence-based gun safety measures—such as banning assault weapons, requiring waiting periods and thorough background checks, and instituting safe storage measures and red flag laws. It will take defeating bad proposals that aim to arm teachers or make it easier to carry concealed weapons. And it will take educators pushing for district-level policies that help make schools safer.

“Gun violence is a solvable problem with a road map for success,” Woodard assures. “And educators can work through their unions to pass resolutions for safer schools, participate in days of action, rally and lobby for change, and create opportunities to address mental health and well-being in schools.”

That work is underway in NEA state affiliates and locals around the nation.

Win Elections, Demand Change

Most educators have not experienced a school shooting. But they, along with their students, are forced to live in a state of anxiety knowing that any given day could be “the day.”

“Believe me, when the balloon pops down the hall, everyone jumps,” says Justine Galbraith, an English teacher in Troy, Mich. “Kids have a lot of feelings about the active shooter drills and the fear we all live with.”

In Galbraith’s view, lawmakers and voters need to hear some hard truths from educators about what the constant threat of gun violence means in a school.

“In my district, educators have to decide whether to lock down or flee—to decide in an instant what’s going to work better to keep kids from getting murdered,” she says. “Obviously, that’s not the job we signed up for.”

Galbraith was already an active member of her local chapter of Moms Demand Action back in 2017, when the Michigan legislature proposed the “Guns Everywhere” bill that would allow citizens to carry concealed weapons in schools and churches.

That was the year she first attended a Troy Education Association meeting to tell members about the dangerous bill and how they could speak out against it.

“My effort was so well received. I just became more active in my local after that,” Galbraith recalls. The harmful bill was defeated.

A few years later, in 2021, came the shooting at Oxford High School—just 20 miles from where Galbraith and her family live. Her own children, 10 and 14 at the time, were shaken. “It was literally too close to home,” Galbraith says. “We all have connections in Oxford.”

MEA doubled down on efforts to organize and mobilize members around the issue of gun violence. Galbraith was involved from the start. She worked with other members to email and call their legislators and teamed up with other organizations for advocacy days at the capitol, supporting the commonsense changes that the majority of Michigan voters wanted.

There was a small but vocal faction of gun rights advocates who, she recalls, “showed up wearing camo, with bullhorns, and tried to intimidate us.” But educators and allies refused to back down.

In April 2023—just a few months after three students were killed and five more injured at Michigan State University—Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed 13 gun safety bills into law, establishing universal background checks for all firearm purchases as well as safe storage requirements among other important changes.

So how did Michigan go from proposing concealed carry in schools to passing a host of gun safety laws in just five years’ time?

It started with winning elections.

“We had a fantastic and successful effort to un-gerrymander the state in 2020,” Galbraith explains. Once fair voting district maps were established, a pro-public schools majority was elected in 2022, flipping control of both houses of the legislature.

“Suddenly all of the work that we’d done over the previous six years started actually moving and ultimately became law,” Galbraith says.

Engage Local Power to Make Schools Safer

On December 10, 2021, a 13-year-old boy at Mitchell Middle School in Racine, Wis., was arrested for bringing a gun to school. The weapon was not loaded, and he made no threats against staff or students.

A few months later, the district installed costly weapons scanners that rely on artificial intelligence and have been known to miss kitchen knives and mistake a lunchbox for a bomb.

Racine Educators United (REU) had concerns about the district’s response on both fronts. The student’s actions were serious, but REU leaders questioned whether he would receive the services he needed in the hands of local authorities. They also pointed out that weapons detectors alone would not reduce the streak of violent incidents at Mitchell that had resulted in more than a dozen staff injuries in recent years.

Though Wisconsin educators’ collective bargaining rights were curtailed in 2011, that did not stop REU from using the union grievance process to demand change. When that didn’t work, REU filed a lawsuit that broke the logjam.

“We called for the creation of a safety committee so that educators and parents have a say in creating policies that don’t push students into the school-to-prison pipeline or use up resources on the wrong things,” says REU President Angelina Cruz.

Quote byMichigan Paraeducator

Staff from NEA’s Health and Safety program supported that work and attended meetings with REU leaders and architects involved in an ongoing $1 billion school construction project. Made possible through educator advocacy, the project is the result of the state’s largest-ever referendum to improve schools, which passed in 2020.

“We’re asking how we can design a safer school,” Cruz explains. “That includes everything from proper air ventilation to rooting out blind spots where violent incidents tend to occur.”

Nationwide, conversations about school buildings now include classroom door-lock systems, shatter-resistant windows that double as emergency exits, and bulletproof whiteboards that can be used to shield students.

Racine educators are focused on preventative measures, including districtwide training on trauma-informed practices and evidence-based programs to help staff de-escalate violent situations.

NEA has crafted violence-prevention and response language (at nea.org/gunviolence) that locals can use to strengthen board policies, employee handbooks, and collective bargaining agreements. The language covers topics such as prohibiting the arming of educators; addressing violence, abuse, and threats against staff; supporting students and educators after an assault; instituting broad health and safety provisions for safer work environments; and establishing joint health and safety committees.

“Educators must have a voice in all of these decisions if we’re really trying to create safer schools,” Cruz says. “That’s what we know.”

Can We Stop This? The Data Say Yes

Safe Storage of Firearms

Red Flag Laws and Programs that Teach Educators and Older Students to Identify and Report Signs of Trouble

Communities Finding Common Ground to Make Conditions Safer for Students and Educators

Commit to Student Mental Health

Travon D. Tillis worked in community mental health for nearly two decades before joining the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), in 2020. “I knew that I could have an even greater impact if I were in a school full-time,” says Tillis, who works at 42nd Street Elementary School, not far from where he grew up.

As a psychiatric social worker, he provides social and emotional learning opportunities for more than 200 students. He also offers targeted supports to the school’s most marginalized students, most of whom are Black and come from families who struggle with housing, medical needs, and food insecurity.

Tillis was also one of dozens of educators at NEA’s convening on gun violence prevention last year. Educators know that improving student mental health is critical to curbing gun violence in more ways than one.

The fear of gun violence holds some students back. “Students can’t learn if they don’t feel safe at school,” Tillis says.

Some of Tillis’ students have heard about school shootings and seen images of the aftermath on TV. Others have been affected by violence in the community, and a few have even lost family members to gun violence.

Schools must not ignore their students’ lived experiences, Tillis says, but rather help them address difficulties, build self-esteem, focus on academics, and seize opportunity.

Research shows that students benefit from relationships with trusted adults at school. And the more skills students acquire in processing emotions and social interactions, the more likely they are to reach out when they need help or when a peer is in distress. Among these trusted adults are school counselors and social workers who help resolve bullying; provide intensive counseling for students in crisis; conduct threat assessments; and work with families, all of which reduces violence in schools.

But that work requires having the staff to do it. The National Association of Social Workers recommends that social worker caseloads do not exceed 250 students, but some LAUSD school social workers were still serving around 1,000 students at the beginning of 2023.

That’s why United Teachers Los Angeles worked with students and the community to develop a student-centered platform before bargaining last spring.

The new contract establishes LAUSD as a model for addressing student needs and commits to adding mental health providers throughout the district.

It will always be up to educators and parents working together to ensure that those commitments are funded and sustained, Tillis says.

“The crisis of gun violence won’t be solved by doing just one thing,” Tillis says. “We have to pass the laws, talk to families, and remain totally committed to our students’ well-being.

Ensuring Safe School Communities

Get more from