Key Takeaways

- Censoring classroom discussion on race and gender or banning books and taking them off shelves isn’t enough for some politicians—now they are zeroing in on state standards to sow chaos and undermine public education.

- This is a national effort to use culture war issues to divide communities.

- NEA members, with support of their unions, remain committed to teach an honest and accurate curricula.

Driving a Wedge Between Educators and Parents

Under the new Florida law that restricts teaching about race, a textbook company submitted a draft lesson plan that removed references to Rosa Parks’ race from a discussion of Jim Crow laws. According to the New York Times, the original lesson stated that Parks was asked to move from her seat because of the “color of her skin.” The revision? “She was told to move to a different seat.” Thankfully, the revision was rejected by the state education department.

Across the country, in South Dakota, proposed revisions to social studies standards would expect second graders to demonstrate the developments and achievements of the high Middle Ages, including the power of the papacy and the founding of the mendicant orders. The previous standard, from 2015, takes a more age-appropriate approach: Second graders are expected to compare holidays that are celebrated in different cultures.

In Missouri, during a committee hearing, Rep. Ann Kelley introduced an anti-LGBTQ+ bill that read: “No classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties relating to sexual orientation or gender identity shall occur.”

Her colleague, Rep. Phil Christofanelli, had some questions:

Rep. Phil Christofanelli: You mentioned George Washington. Who is Martha Washington?

Rep. Ann Kelley: His wife.

PC: Under your bill, how could you mention that in a classroom?

AK: To me, that’s not sexual orientation.

PC: Really? So, it’s only certain sexual orientations that you want prohibited from introduction in the classroom? Could [Martha Washington] be mentioned under … your bill?”

AK: I don’t know.

“This bill is not concerned with teaching about sexual orientation in general, but aims to erase anyone who’s not heterosexual,” says NEA Deputy General Counsel Jason Walta.

These examples are not the exception. “They fall in line with a national effort to use culture war issues and co-opt language, such as ‘critical race theory’ and ‘indoctrination’ to drive wedges between educators, parents, and communities,” Walta explains. “The end goal: Privatize public education.”

A Lesson Set Ablaze

On May 31 – June 1, 1921, White rioters in Tulsa, Okla., murdered hundreds of Black residents. They looted and burned down homes, businesses, schools, and community centers in the thriving Black community of Greenwood—often called Black Wall Street.

LeeAnne Jimenez, a teacher of 25 years and vice president of the Tulsa Classroom Teachers Association, was raised 60 miles northeast of Tulsa and didn’t know anything about the massacre or the wealthy Greenwood community that previously existed—until she was asked to teach it in 2000.

As part of a lesson on the balance of power among cultures in the 1920s, Jimenez and another teacher had their third, fourth, and fifth graders learn about Greenwood’s residents: Did they own a movie theater, run a taxi company, or own a one- or two-story building? What materials were the buildings made of?

“We wanted to give them a sense that this was a prosperous community,” Jimenez says. Students spent weeks drawing a scale model map and placing small cubes to represent the businesses.

“And then one night—when students were gone—we burned it, because that’s what happened,” Jimenez says. “It was some of the most powerful learning I’ve ever been a part of.” Student wrote poetry and had frank conversations about the desires of one community to create power over another and talked about how a person’s identity changes when exposed to racial trauma.

“This wasn’t in our standards, but if you want to develop empathy and a whole person, you have to tap into all [facets] of history, not just, ‘By the way, on May 31, 1921, there was a race riot,’” Jimenez says. “That’s what the standards ask of us today: Teach them the dates and times of these events.”

When a Political Stunt Becomes Law

An Oklahoma law, signed by Gov. Kevin Stitt in 2021, restricts teaching that could make a student “feel discomfort, guilt, anguish or any other form of psychological distress on account of his or her race or sex,” among seven other banned concepts.

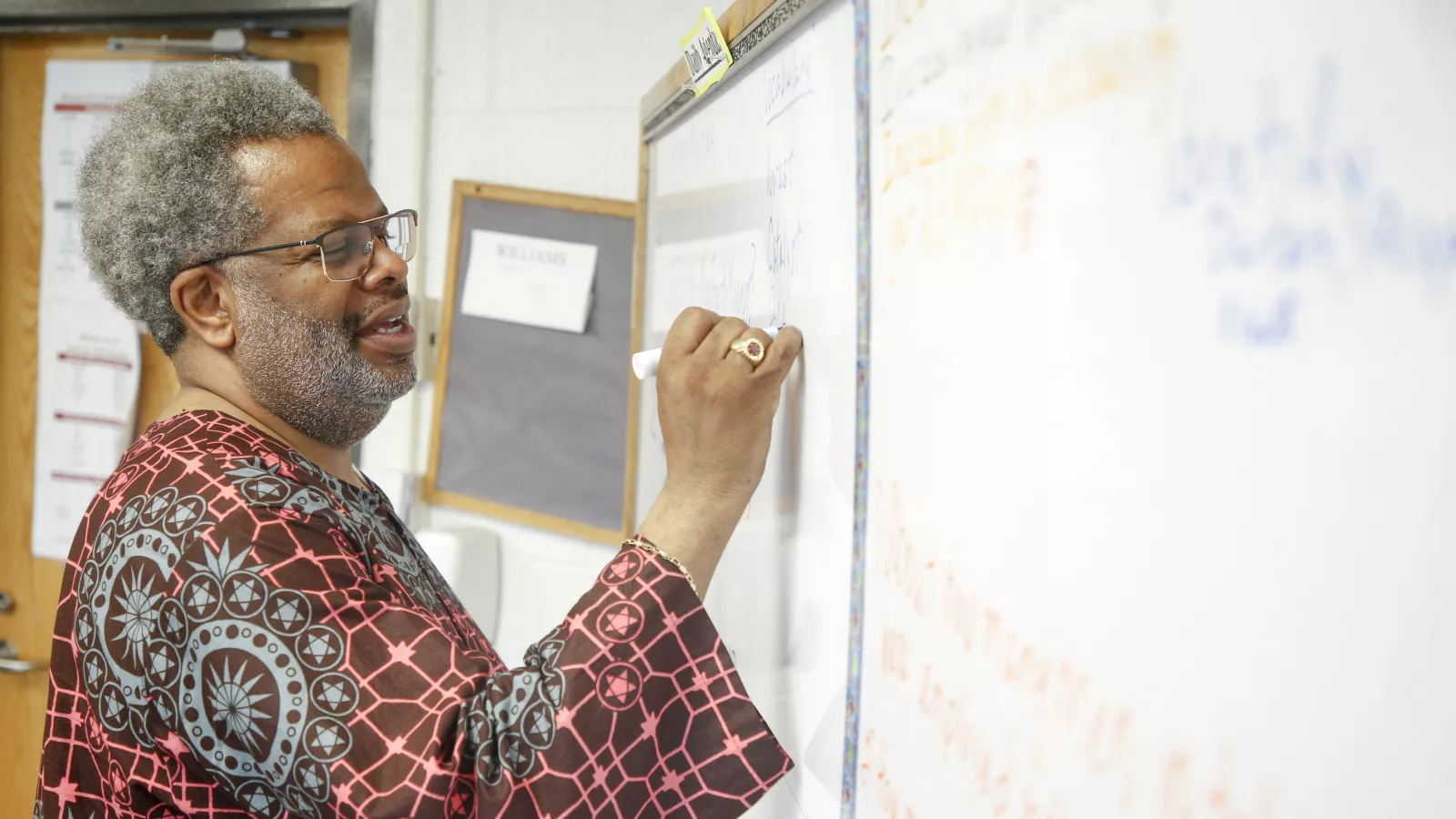

But this concept, also pushed by other states, is a far-right talking point that has been codified into law. “History doesn’t say who’s at fault,” explains social studies teacher Frederick Smitherman, who teaches Advanced Placement (AP) U.S. history, African American studies, and U.S. government classes to freshman in Tulsa Public Schools.

“History says what happened, and so I have kids critically think, analyze, support, and … talk about the whole story, not [just] give them a right or wrong answer.”

Darren Williams, also a high school social studies teacher in Tulsa, says, “Education is now being used as a weapon, and to the degree that it’s so politicized, if you don’t see it a [certain] way, you’re an enemy.

“[This] seems to be about politics,” he adds. “It really does not have the interest of children, of students, at heart.”

Case in point: In 2021, conservative activist Chris Rufo tweeted, “We have successfully frozen their brand—‘critical race theory’—into the public conversation and are steadily driving up negative perception. We will eventually turn it toxic, as we put all the various cultural insanities under the brand category.”

What Actually Happens in Mr. Williams’s U.S. History Class?

Williams is one of 61 teachers in the country who has been selected to pilot the AP African American studies course—the same one rejected in February by Florida’s governor.

And while far-right politicians across the country accuse educators of making students “feel bad,” Williams can tell you what actually happens in his classroom.

Students study topics including lynching, the transatlantic slave trade from Africa to the Americas, and the deaths from suffocation, malnutrition, disease, and suicide that took place on the slave ships. The class explores information about who owned slave ships and which corporations today have connections to those ships.

They learn what life was like for enslaved people, covering breeding farms as well as the resistance and revolts.

“Instead of my students being ashamed or taking what happened in history as having a negative effect on them, it makes them engage more,” says Williams, explaining that students see the connections between violence against Black people in the past and today.

After the unit session on lynching, he adds, “One of my White students said, ‘We’ve got to be better. They didn’t fix these problems. We have to.’”

Williams’ suggestions for those who want to protect students from feeling badly about the facts of history?

“Know what you’re talking about, because the criticism and pushback has been uninformed. … If you don’t intend to be informed, get out of the way.”

Williams adds, “We take our jobs and the lives and futures of our students serious enough to make sure we present information that’s going to help them to be good people first and then good citizens.”

Say No to Whitewashing History

Kelsey Lovseth, an American government teacher, in Brookings, S.D., worked with a team of educators and lawmakers to skillfully revise the state’s social studies standards, in 2021.

“They were rooted in good pedagogy,” she says.

But when the draft was publicly released, much of what they had created had been stripped out—particularly references to the state’s Indigenous population. Plus, a large amount of recitation, memorization, and biblical references had been added.

Gov. Kristi Noem pulled the draft standards from review and formed a new group. This time, only three educators were a part of the 15-person commission. The new commissions’ standards were heavily prewritten by a professor from Michigan’s Hillsdale College, which tends to push religious and age-inappropriate standards for younger students.

The new standards were so egregious that several people on the new commission openly opposed them. Lovseth and her union, the South Dakota Education Association (SDEA), mobilized against the standards.

SDEA led a drive to educate members about how standards are adopted. The union informed members that public hearings are required by law; that members of a commission are appointed by the governor, and not elected; and that a school board’s decision to opt out of standards has consequences.

“We didn’t necessarily have that type of advocacy prior to this,” Lovseth shares. “We have been fortunate that the state affiliate has led the charge, and that we have been supported by a lot of different groups”

The Associated School Boards of South Dakota, which represents 850 local school board members, provided its members with suggested language to

oppose the Hillsdale College version of the standards. At the time of reporting, 23 boards had publicly opposed this version. The state parent-teacher organization has partnered with SDEA, too.

“This has been a coalition-building opportunity, and it’s been very grassroots,” Lovseth says. “We have first-grade teachers, who have several years left before they retire, looking at these standards and saying: ‘This is not what I want my first graders to learn. What can I do to help?’”

“We’re super connected,” says Lovseth of the educators across her vast state. “To see all the relationships we’ve built with our local school boards who have put themselves on the line politically to stand up with us has been remarkable.”

And it gives her hope that these bad policies will be defeated.

What You Can Do to Protect Students’ Learning

To protect students’ freedom to learn, educators must get involved. Evidence supports that when educators, their unions, and allies engage in advocacy, they’re able to fend off bad legislation.

In Montana, for example, one-third of the Montana Federation of Public Employees was at the ready when politicians introduced a bill to ban social and emotional learning and a so-called parents’ rights bill, forcing educators and school counselors to out LGBTQ+ kids and requiring written parental consent before using a new name or pronoun.

Educators sent thousands of text messages and made hundreds of calls to help defeat these bills.

Kelsey Lovseth, a 17-year educator and member of the South Dakota Education Association, who was involved in fending off similar legislation in her state, suggests the following:

1. Remember: Most Americans, including parents, are on educators’ side and want the same things, including curricula that provide students with the positive and negative aspects of our history.

2. Be informed: Know how standards are adopted in your state and when they get adopted.

3. Get involved: Sign up for a curriculum review committee or to help write curricula, if allowed in your district.

4. Learn more: Get to know your school board policies. The board has a tremendous impact on how a school district operates.

5. Contact your union: Ask what you can do to help and take part in collective actions. Find out about your rights in the workplace. For example, know that your speech and activism are most protected outside of work, when you’re speaking up as a citizen on a matter of public concern.

Education Justice

Get more from