Key Takeaways

- Despite a slight decrease from 2018 to 2019, the 'teacher pay gap' remains vast.

- The erosion of educator pay over the years, coupled with the marginalization of the profession, has led to an alarming teacher shortage,

- With the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic likely to be long and severe, it is imperative that lawmakers not repeat the mistakes of a decade ago, when they slashed school funding while cutting taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals.

Oklahoma has one of the largest teacher pay penalties in the United States at 29%. That is, the average public school teacher in the state earns 29% less in weekly wages than other college-educated workers with similar experience.

That gap, says Shawna Mott-Wright, president of the Tulsa Classroom Teachers Association, makes it extremely difficult to recruit and retain good educators into the profession. Oklahoma, which ranks 34th in the nation in average teacher salaries, according to the National Education Association, has the fourth largest teacher penalty.

“The pay here is abysmal,” says Mott-Wright. ”One-fourth of our members have second jobs, and half of that group has three jobs. How is this supposed to help our students? Well, it doesn't.”

Mott-Wright was talking about the erosion of competitive educator salaries during a webinar on Oct. 14 sponsored by the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), which also included NEA President Becky Pringle, and EPI researchers Lawrence Mishel and Sylvia Allegretto. (You can watch the webinar below)

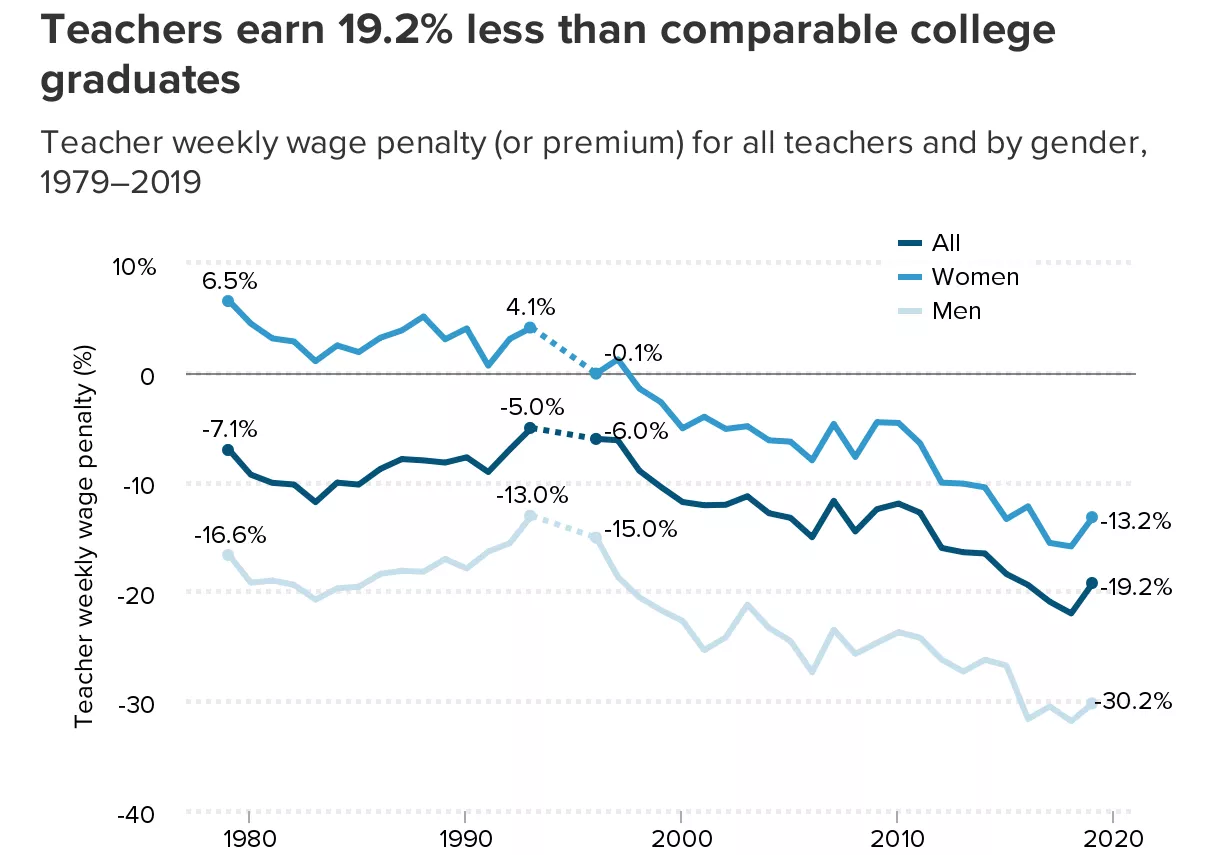

A few weeks ago, EPI released its latest survey of the teacher pay gap. On the surface at least, the report revealed some encouraging news: nationally the pay gap actually decreased from 22% in 2018 to 19% in 2019.

This decline may be the result of the successful #RedforEd protests that swept through many parts of the nation in 2018 and 2019.

“There is no doubt that #RedforEd re-established teachers as heroes, and that they are underpaid and underappreciated,” MIshel said. Quite the turnaround from a decade ago when public school educators – public education in general - were scapegoated for the perceived failures of the education system while school funding was being slashed right and left.

Still, the teacher pay gap remains vast. Until last year, it had been growing steadily. In 1996, educators earned on average 6% less weekly wages than comparable workers. By 2018, the teacher pay penalty had ballooned to 22%.

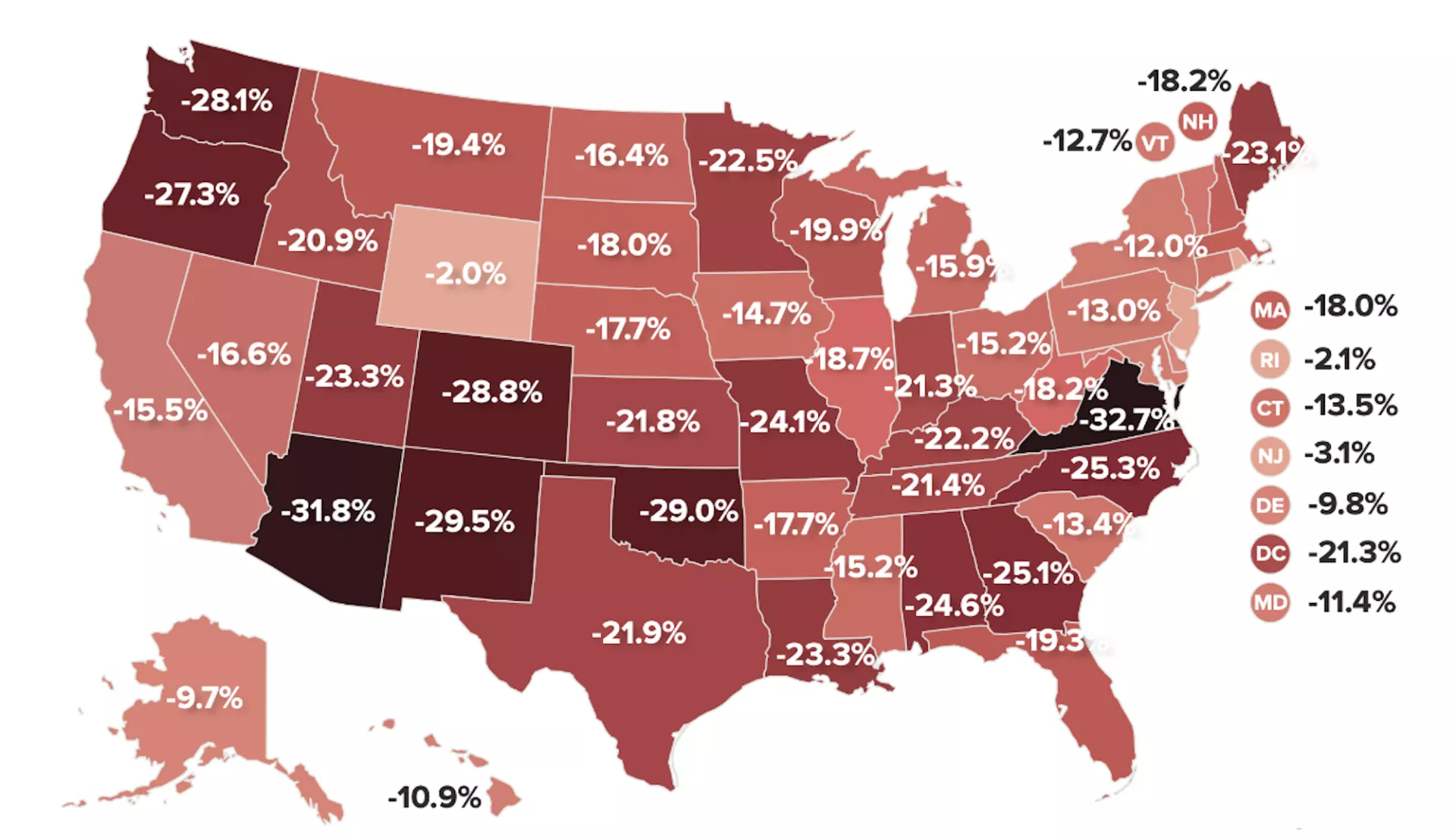

Overall, the penalty ranges from 2.0% in Wyoming to 32.7% in Virginia and exceeds 20% in 21 states and in the District of Columbia. Teachers in these states are paid less than 80 cents on the dollar earned by similar college-educated workers.

The teacher pay penalty has grown significantly among women. In 1960, female teachers earned 14.7 percent more than comparable female workers, an advantage that lasted throughout most of the 1970s but was completely erased by the 1990s. By 2019, they were earning 13.2 less than comparably-educated female workers. The penalty is much larger for men. In 2019, male teachers earned 30.2% less than similar male college graduates.

“In order to recruit and retain talented teachers, school districts need to address the inadequacy of teacher pay,” Mishel said. “It’s not just a fairness issue. Eliminating the teacher pay penalty is crucial to building the teacher workforce we need.”

Hurting Educators Means Hurting Students

The erosion of educator pay over the years coupled with the marginalization of the profession has led to an alarming teacher shortage, Pringle said. "Overall, fewer people are entering the profession and more are leaving".

Pringle also emphasized that lower salaries undercut the national need to recruit, develop, and retain educators of color. Research has continually shown that students of color who are taught by a teacher of the same race or ethnicity perform better in school.

And because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the profession may soon be facing an unprecedented exodus. In addition to financial pressures, Pringle said, too many educators are feeling disregarded as some districts have moved head with in-person reopening without adequate safety protocols. ”They just don’t feel safe.”

With the economic crisis triggered by the pandemic likely to be long and severe, Pringle, Mishel and Allegretto agreed it was imperative that the nation not repeat the mistakes of more than a decade ago when the Great Recession hit. Year after year, lawmakers in too many states slashed school funding while cutting taxes on corporations and wealthy individuals.

"The Great Recession was used to institute permanent pay cuts, including lowering teacher pay... Recessions are an opportunity for those who have long-been looking to dismantling public goods, all in the name of lower taxation," said Allegretto. “This time will be no different.”

For educator and their students, the pandemic has been an unprecedented crisis, but for for-profit education businesses and proponents of school privatization, it has been something else: an opportunity to further divest from and dismantle public education. (In an interview with right-wing radio talk show host Glenn Beck in May, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos said “This is an opportunity to collectively look very seriously at the fact that K12 education for too long has been very static and very stuck.”)

“We’re once again hearing the same rhetoric,” said Allegretto. “State and local funding are being called ‘bailouts,” as if aid to states during a pandemic is something bad. If they succeed, our students will pay the price.”

In 2018, it took the RedforEd movement to help turn the tide and force legislatures to finally begin reinvesting in public education. “The movement led to some important changes,” Allegretto said. “Unfortunately, we’re going to need much more of this in the future and in the near future. The good news is that the public is now on our side.”

Thanks to their tireless activism, Oklahoma educators scored a few key victories for educator pay and school funding. The statewide educator “walkout” in 2018 led to the largest single year increase in education funding in the state’s history, including a pay raise for teachers and education support professionals.

”We were 24% below 2008 funding levels. Now we’re only 15% below 2008 levels,” said Mott-Wright. “So the hole was filled a little bit, but not enough.”

And despite the progress, Mott-Wright says educators recognize how much more work there is to be done.

“We continue to feel undervalued and expendable. Why is our expertise not treated the same as the expertise as other professionals? If we truly want to do what is best for students, we have to what is best for teachers. If we are hurting teachers, we are hurting students.”