When teacher and author Torrey Maldonado was in third grade, his mother brought home A Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats—the beloved book about a young Black boy exploring his city in fresh snow.

Until then, Maldonaldo—who is Black and Afro-Puerto Rican—had never seen a kid who looked like him in a book. “I thought that book was me! I thought the mother was my mom,” he says. “What made that book so precious to me is it took my neighborhood and made me see the magic in it.”

Growing up in the 1980s in a New York City housing project that Life magazine called “the crack capital of the world,” Maldonaldo was what his teachers called “a reluctant reader.” And he wasn’t the only one. “When I looked to the left of me, I saw reluctant readers. When I looked to the right of me, I saw reluctant readers,” he says. “This was not by accident. It was unintentional, but it was structural—the only books available to us didn’t have us in them.”

An Evolution in Children’s Books

In 1985, less than 1 percent of children’s books spotlighted Black characters. Twenty years later, not much had changed. In 2015, children were about five times more likely to encounter a talking truck or dinosaur on the page than a Hispanic character.

But by 2019, more than 12 percent of U.S.-published children’s books featured Black characters, according to the University of Wisconsin’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center. Additionally, 9 percent of books featured Asian characters; 6.3 percent featured Hispanic characters; and less than 1 percent had Native American or Alaska Native characters. While children’s books still aren’t as diverse as the children who read them, progress is being made.

Mirrors and Windows

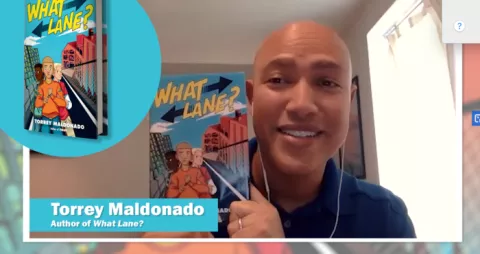

Today, Maldonado is a New York City teacher and author of What Lane?, a middle-grade book about a mixed-race student who faces racism and prejudices in his community.

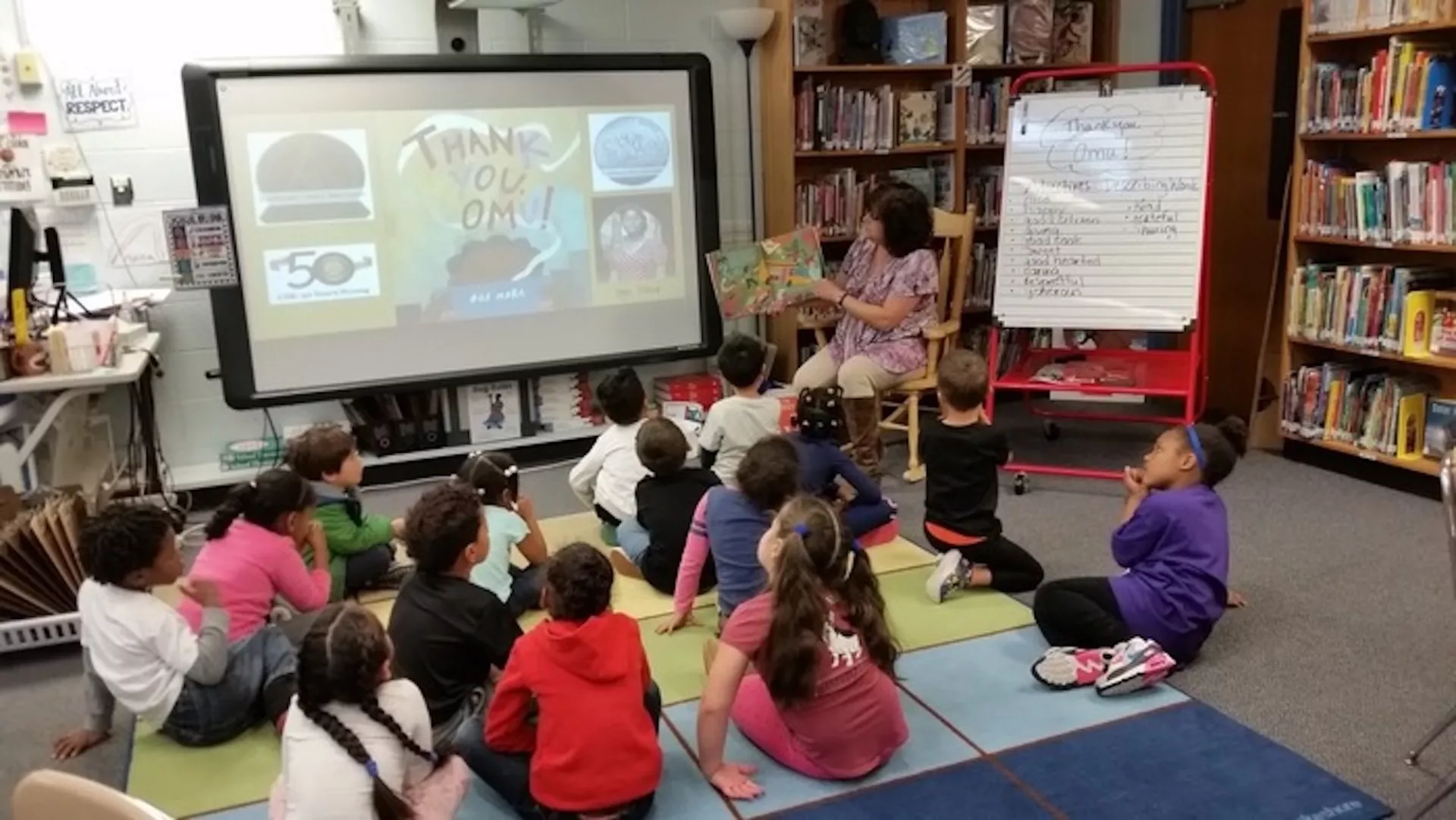

Books with diverse characters, like Maldonado’s, serve multiple purposes in children’s hands. For Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native students, who are often stereotyped or overlooked in popular culture, it’s personally validating and academically engaging to see themselves and their life experiences reflected on the pages. School librarians call these books “mirrors.” It’s equally important for white children that these books serve as “windows” into the experiences

of children of color.

Maldonado and bestselling authors such as Angie Thomas, Jason Reynolds, and Kwame Alexander are part of a vanguard of children’s authors who are affixing mirrors to their pages —and opening windows.

Empathy is Key

Not long ago, Maldonado heard from a school librarian whose students had read a passage of What Lane? in which Stephen, the main character, is accused of stealing a cookie. One of her students raised her hand and asked, “Is this a long-ago book or a right-now book?” Another answered: “It’s right now. My dad was harassed at the grocery store last week.”

When the only stories told in a school library are white people’s, then the message to Black, Hispanic, Asian or Native students is clear: Your experience doesn’t matter. Meanwhile, “If you’re a white kid who only sees and reads about white kids, you can get an inflated sense of how important whiteness is,” says Maryland school librarian Melissa McDonald.

Mirrors are important. So are windows. With so many schools still racially segregated—the Economic Policy Institute has found 70 percent of Black students are attending segregated schools— it’s hard for children of different races to connect and care about each other. Often white students don’t have windows into the racism that their peers face—and if they don’t see it, they can’t help stop it.

“I’ve had educators tell me that it’s a good book, but it’s not for their students, because their students are white,” says Maldonado. “When I hear that, I think, Wow! You only want to give white kids books about white kids and white experiences? … How are we ever going to build empathy?”

Learning a Different Story

A good book can help you understand what it’s like for people who don’t share your race, religion, sexual orientation, or socio-economic status. Diverse books teach empathy, says Erika Long, a middle school librarian in Tennessee.

One of Long’s favorite books is No Fixed Address by Susin Nielsen about a boy named Felix, who is almost 13 and lives with his mom and pet gerbil in a van. “It’s a tough topic, but it’s a way to say to a kid that you’re not alone. Other people go through this. There’s a message in there—there’s hope and you’ll be okay,” says Long.

“And if you’re not homeless, if you’re a kid who has everything, it’s about showing them that kids are out there in different situations,” Long says. “How can we show them kindness and how can we build relationships without having judgement?”

Diverse books opened a window for Maldonado. He remembers seeing that Life magazine with his neighborhood on the cover and how uncomfortable it made him feel. “My mom looked at my face and said, ‘Well, what are you going to do about it? Be the change you want to see,’” he recalls.

“When I got older, it clicked,” he says. “If you don’t like the narrative about you and your community, your peers and your classmates, then you can rewrite the story.”

Join NEA's Read Across America in Celebrating Diverse Books!

KidLitTV

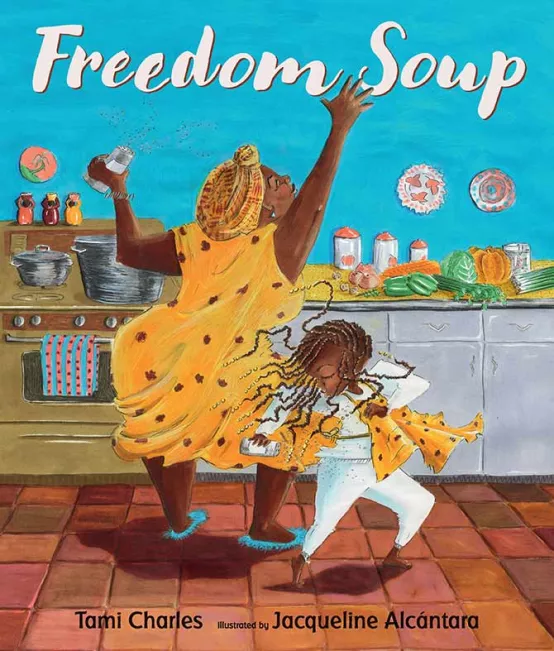

Freedom Soup

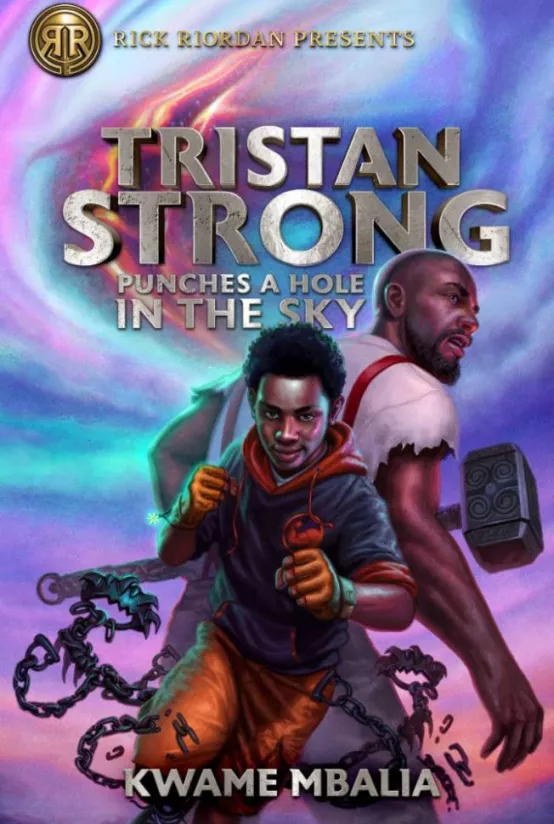

Tristan Strong Punches a Hole in the Sky

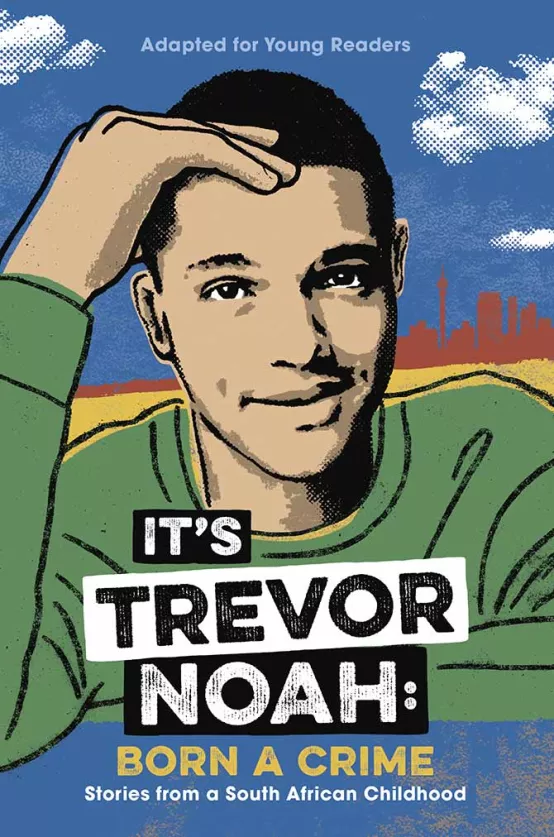

It’s Trevor Noah: Born a Crime

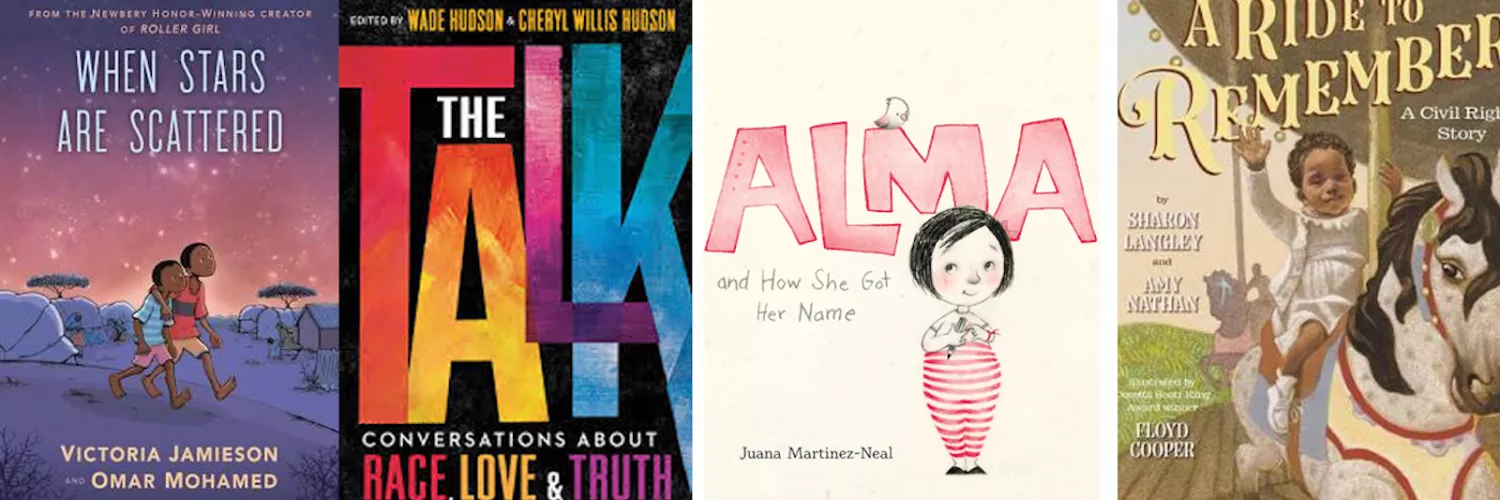

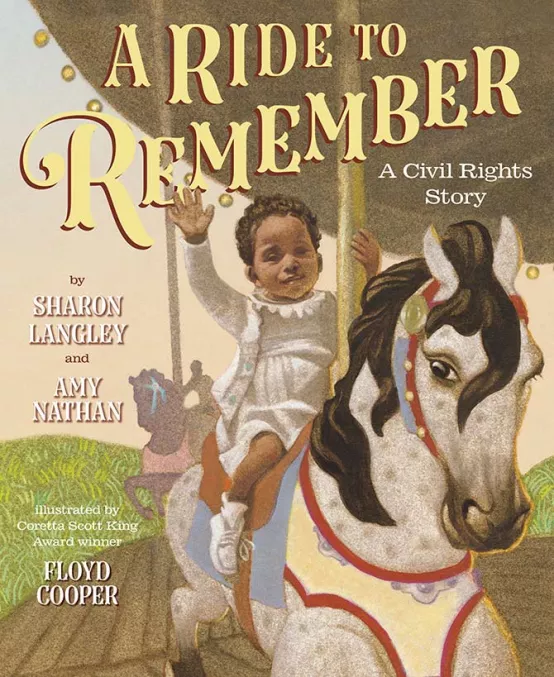

A Ride to Remember: A Civil Rights Story

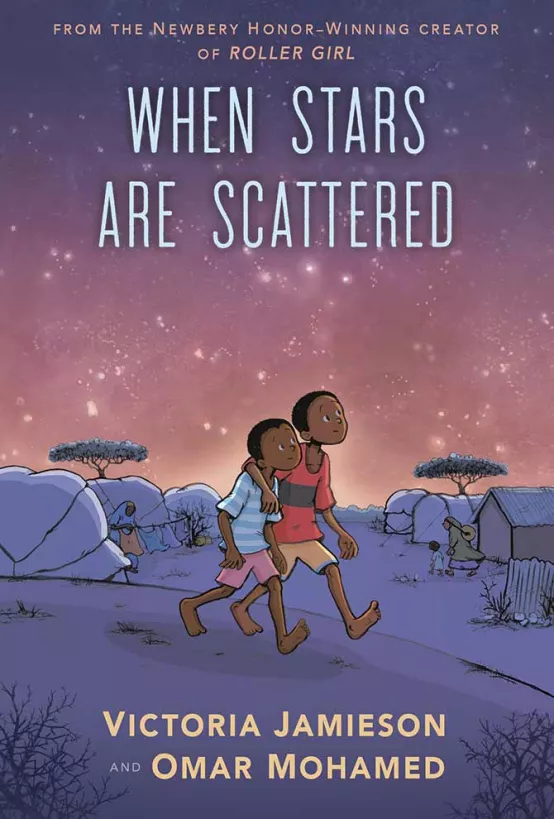

When Stars Are Scattered